Indigenous leader.

Full name, including alternates: Peguis (Be-gou-ais, Be-gwa-is, Pegeois, Pegouisse, Pegowis, Pegquas, Pigewis, Pigwys), baptized William King

Date of birth: circa 1774, near modern day Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

Date of death: 28 September 1864, St. Peter’s Reserve, Manitoba

Place of burial: St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church, East Selkirk, Manitoba

Chief Peguis was born to unknown parents near Sault Ste. Marie in Ontario, Canada circa 1774. Sometime in the 1790s, he led a group of Anishinaabe (Saulteaux) west into what is now Manitoba, settling at Netley Creek just south of Lake Winnipeg.

Peguis has been historically praised for his alliance with and aid to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the Selkirk settlers who arrived at Red River from Scotland in 1812, but his impact on Manitoba history went beyond ensuring the survival of the Red River Colony. Peguis’ roles as diplomat, leader, and advocate for First Nations are key reasons he should be remembered in First Nations and Manitoban history. Peguis was a strong and caring leader who consistently put the interests of his own people first, despite outside pressures. He accepted colonial teachings and ways of life only when he believed they were to the benefit to his people, and was an advocate for First Nations’ land titles and rights.

Peguis was a skilled diplomat who negotiated many agreements and forged various friendships on behalf of the Anishinaabe while being fair and considerate to the other parties involved as well. Though sources are not entirely sure of the specific year, there is general agreement that Peguis led his group of Anishinaabe from near modern-day Sault Ste. Marie sometime in the 1790s. This means that he was somewhere between his late teens and mid twenties. With the devastating effects of colonialism diminishing the Indigenous populations already living there, Peguis’ group settled at the uninhabited Netley Creek and negotiated with the local Cree and Nakoda (Assiniboine) to allow his group to live on and use the land in the area. [1] The three groups also saw potential for an alliance against their common enemy, the Dakota and Lakota (Sioux), leading to better relations between them.

Peguis was a leader who preferred to build strong relationships rather than create tension or conflict. When the Selkirk settlers arrived at Red River under the auspices of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Peguis allowed them to live on the land and even helped them through the first few harsh prairie winters. He also exchanged gifts and mutual aid with the colonists to build a strong relationship between the two groups. When these Selkirk settlers and HBC employees came into conflict with the North West Company (NWC) ahead of the Battle of Seven Oaks (19 June 1816), Peguis attempted to negotiate on behalf of the HBC contingent, to no avail. Peguis aided the colonists’ evacuation in from Red River in the wake of the battle. [2]

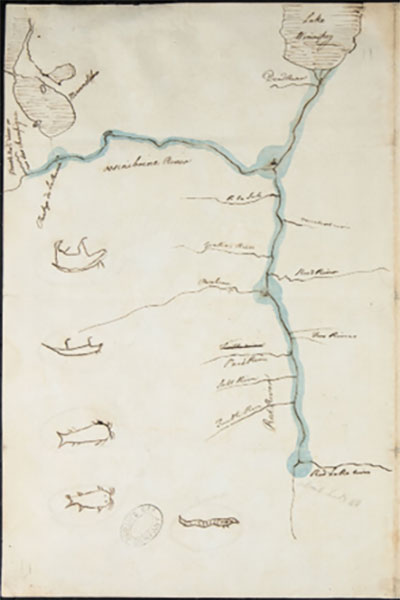

Peguis was also a leader in the negotiation and signing of the Selkirk Treaty of 1817. Peguis along with Cree chief Le Sonnant (Mache Whesab, Many Sitting Eagles) and fellow Anishinaabe leaders Le Premier (Oshki-doowad, Anishinaabe), L’Homme Noir (Gaayyaazhiyeskibino’aa) and La Robe Noire (Makadewikonaye) and the Earl of Selkirk, signed the first land rights treaty in what is now western Canada. [3] The Treaty stipulated that in exchange for the rights to settle a parcel of land spanning 300,000 square kilometres along the Red and Assiniboine rivers, the HBC would pay the Anishinaabe an annual rent of one hundred pounds of tobacco. [4] The treaty and accompanying map officially recognized that the Selkrik settlers were being permitted to live on Indigenous land, as prior to its signing there was only a loose verbal agreement. Rather than an outright sale, Peguis aimed to prioritize the long-term benefit of his people by preserving their ownership of the land and having them receive ongoing payment for its use. Unfortunately, the HBC did not live up to this promise and in the 1850s and 1860s Peguis was highly critical of the Company’s failure to fulfill the terms of the treaty.

Peguis was a strong leader who led the Anishinaabe through times of great change, while managing to maintain their identity. Anglican missionaries under the Church Missionary Society arrived at Red River 1820. Peguis developed a cautious friendship with first John West and then Reverend William Cockran, the latter of whom pushed for Peguis and his band at Netley Creek adopt agriculture. The CMS established a mission in Peguis’ territory, at what would become St. Peter’s Reserve, in 1833 to encourage and assist with agriculture. Peguis was steadfast in his belief that his people would not accept a sedentary agricultural lifestyle, but by the late 1830s agreed settle at St. Peter’s where he and many other residents had titles to their land. [5]

Peguis’ general wariness of settler ways meant that he had been reluctant to be baptized by the Anglican missionaries but a year after his son George passed away Peguis took baptism. [6] He took the baptismal name of William King, the first name to honour William Cockran and the last name to represent his status as chief in line with that of a British king. Like with the adoption of agriculture, Peguis met with some resistance among the Anishinaabe for this decision, and especially among Elders and Midewiwin practitioners. [7] But Peguis was steadfast in his choice once it had been made, and many would follow in his footsteps. Historians who have researched Peguis argue that this conversion was not only spiritual, but political as well, as it deepened the Anishinaabe’s ties with the settlers by bringing their ways of living closer together. [8] Peguis, as chief, was clearly committed to maintaining his peoples’ culture and way of life. On the other hand, he was not opposed to change if he believed it was necessary. He did not take such a critical decision lightly, and waited until he was sure it was the correct course of action.

Peguis was a notable advocate for First Nations land rights, and laid the groundwork for many methods of advocacy used in land title disputes and other disagreements to this day. He lamented that the Selkirk Treaty was not being upheld in various ways, not only because the colonists had never paid the annual rent but also because the HBC was sold selling parts of the land which had never been given to them, but rather rented out to allow them to settle there. [9] He wrote several letters about the treaty and other issues, which were likely penned by penned by one of his sons due to his limited literacy in English. At least one of these letters was submitted as evidence to the 1857 British parliamentary investigation into the HBC, and particularly its relationships with Indigenous peoples. [10] Despite this disgruntlement, Peguis maintained peaceable relations with Red River settlers. Rather than demanding they leave or buy the territory they claimed from the Anishinaabe, he simply asked that they maintain the original agreement and pay the rent. [11] One of these letters, a collaborative effort between Peguis, his son Henry Prince, and other First Nations leaders at Red River, was known as the “Indian Manifesto.” [12] In it, the authors outlined their demand that any settlers newly cultivating lands would have to pay an annual rent as acknowledgement of Indigenous land rights. In this case, Peguis was not only advocating on behalf of the Anishinaabe but working with others to advocate on their behalf as well.

The impacts of Peguis’ work as an advocate for Indigenous rights continued after his death, as Peguis’ agreements with settlers were formative in the later Anishinaabe understandings of their land rights in the region. Peguis died in 1864, seven years before his son Henry Prince signed Treaty One as Peguis’ successor, and is buried at the St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church. The concepts that Peguis and the other signatories of the Selkirk Treaty had laid the foundation for, such as annual payments and the idea that the First Nations signatories would retain land rights, were realized in Treaty One, likely as a result of the Selkirk Treaty and Peguis’ advocacy. [13]

From the very outset, Peguis demonstrated that he was a bold leader who was capable of guiding the Anishinaabe through great challenges. The strong presence of Anishinaabe people and culture in Manitoba today can be traced directly back to this endeavour that Peguis led.

A monument by sculptor Marguerite Judd Taylor was installed in Kildonan Park in 1923 with funding from the Lord Selkirk Association of Rupert’s Land, which was established in 1908 to honour Lord Selkirk and commemorate the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the Selkirk Settlers (Figure 2).

Chief Peguis was commemorated by the Manitoba Heritage Council with a plaque installed at St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church in 1982.

In 1991, Winnipeg Route 17 was named Chief Peguis Trail in commemoration of Peguis. There are three plaques on the west side of the trail dedicated to Peguis.

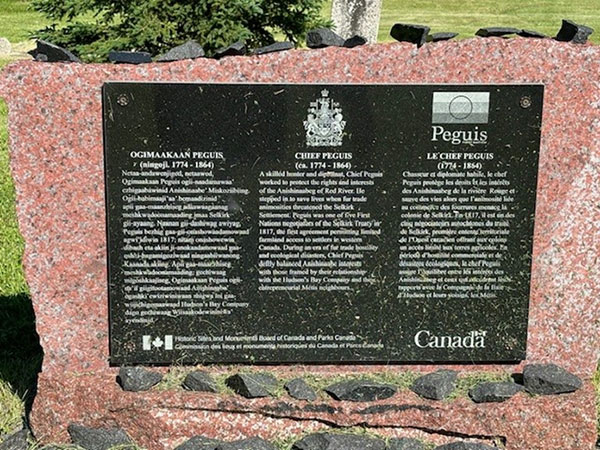

Chief Peguis was designated a National Historic Person by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada circa 2008. The commemorative plaque was installed near his grave site in the St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Cemetery in East Selkirk, MB.

A new statue of Peguis is set to be unveiled on the Manitoba Legislature grounds in September 2025. This statue will also feature four stones containing bronze medallions, meant to represent the four other First Nations signatories (Mache Wheseab, Mechkaddewikonaie, Kayajieskebinoa and Ouckidoat) to the 1817 Selkirk Treaty. A fifth large stone will display a medallion representing Lord Selkirk and King George III, on whose behalf Lord Selkirk signed the treaty. The installation is designed by J. Wayne Stranger of Peguis First Nation.

Map that accompanied the 1817 Selkirk Treaty showing the lands that the HBC was given permission to settle.

Source: Hudson’s Bay Company Archives

Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaque, Chief Peguis, located at St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church Cemetery.

Source: Erin Millions

See also:

Memorable Manitobans: Peguis [William King] (c1774-1864)

Memorable Manitobans: Henry Prince “Red Eagle” [Mis-koo-ke-new] (1819-1899)

Memorable Manitobans: Thomas George “Tommy” Prince (1915-1977)

Events in Manitoba History: Treaty One (August 1871)

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Chief Peguis Monument (Kildonan Park, Winnipeg)

Historic Sites of Manitoba: St. Peter Dynevor, Old Stone Church and Cemetery (RM of St. Andrews)

Historic Sites of Manitoba: St. Peter Dynevor Anglican Rectory / Dynevor Indian Hospital / St. John’s Cathedral Boys’ School (RM of St. Andrews)

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Chief Peguis Trail, Peguis’ Totem and Chief Peguis Plaques (Winnipeg)

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Chief Peguis Junior High School (1400 Rothesay Street, Winnipeg)

“St. Peter's Dynevor, The Original Indian Settlement of Western Canada,” by Rev. T. C. B. Boon

MHS Transactions, Series 3, No. 9 (1952-1953)“Peguis – Friend of the Pale Face” by Nan Shipley

Manitoba Pageant, September 1956.“Site Review: St. Peter’s and the Interpretation of the Agriculture of Manitoba’s Aboriginal People” by Sarah Carter

Manitoba History, No. 18 (Autumn 1989)“‘Your Great Mother Across the Salt Sea”: Prairie First Nations, the British Monarchy and the Vice Regal Connection to 1900” by Sarah Carter

Manitoba History, No. 48 (Autumn/Winter 2004-2005)“Review: Donna G. Sutherland, Peguis: A Noble Friend” by Edward A. Jerome and Ruth Swan

Manitoba History, No. 50 (October 2005)“Peguis, Woodpeckers, and Myths: What Do We Really Know?” by Donna G. Sutherland

Manitoba History, No. 71 (Winter 2013)Peguis, Dictionary of Canadian Biography IX, 626-627

Review: Donna G. Sutherland, Peguis: A Noble Friend by Edward A. Jerome and Ruth Swan

Manitoba History, Number 50, October 2005

Chief Peguis Last Will and Testament, Friends of Upper Fort Garry.

Journal of Frances Ramsay, selection relating to Chief Peguis, original held by the Hudson’s Bay Company Archive.

Peguis First Nation, “About.”

Edward Albert Thompson, Chief Peguis and His Descendants (Winnipeg: Peguis Publishers, 1973).

1. Manitoba Historic Resources Branch (MHRB), “Chief Peguis” (Winnipeg: Department of Cultural Affairs and Historic Resources, 1982) 1.

2. MHRB, “Chief Peguis,” 2.

3. Maureen Matthews, “A history of relations between Selkirk settlers and Indigenous residents at Red River,” Pegius-Selkirk 200, 4 July 2017.

4. Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, “The Selkirk Treaty and Map.”

5. Sarah Carter, “‘They Would Not Give Up One Inch of It’: The Rise and Demise of St Peter’s Reserve, Manitoba,” in Indigenous Communities and Settler Colonialism, eds. Z. Laidlaw and A. Lester (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) 175.

6. MHRB, “Chief Peguis,” 8.

7. Niigaanwewidam Sinclair, “The Illegal Surrender and Relocation of the St. Peter’s Band,” lecture, Canadian Mennonite University (January 2018).

8. Warren Cariou and Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, “Peguis,” Manitowapow: Aboriginal Writings from the Land of Water, (Winnipeg, Manitoba: HighWater Press, 2011), 13.

9. Peguis (William King), “Letter from Peguis to the Aborigines Protection Society.”

10. “Letter from Peguis, chief of the Saulteaux tribe at the Red River settlement, to the Aborigines Protection Society, London,” Tribe at the Red River Settlement, to the Aborigines Protection Society, London,” in F. W. Chesson to H. Labouchere, London, June 7th, 1857, Appendix No. 16, Report from the Select committee on the Hudson's Bay company: together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, appendix and index (London: House of Commons, 1857) 445-446.

11. Peguis (William King), “Letter from Peguis to the Aborigines Protection Society.”

12. Aimée Craft, Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty: An Anishnabe Understanding of Treaty One (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2013), 43.

13. Craft, Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty, 38-39.

This page was prepared by Alistair Smith, a fourth-year undergraduate student in history at the University of Winnipeg. He is interested in various areas of history, particularly the Aztec Empire and Europe post-Second World War.

This article was produced as part of a collaborative public history project between students in the Department of History and Joint Masters History Program at the University of Winnipeg, the Southern Chiefs’ Organization, and the Manitoba Historical Society. Honours and Masters students researched and wrote digital public history articles that align with the Southern Chiefs’ Organization 25th Anniversary History Project and contribute to the expansion of Indigenous history content on the Manitoba Historical Society website. Course: Commemorating Indigenous Histories, HIST-4614/GHIST-7513, Winter 2025, Instructor: Dr. Erin Millions.

Page revised: 26 February 2026

Memorable Manitobans

This is a collection of noteworthy Manitobans from the past, compiled by the Manitoba Historical Society. We acknowledge that the collection contains both reputable and disreputable people. All are worth remembering as a lesson to future generations.

Search the collection by word or phrase, name, place, occupation or other text:

Custom SearchBrowse surnames beginning with:

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | Y | ZBrowse deaths occurring in:

1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026

Send corrections and additions to this page

to the Memorable Manitobans Administrator at biographies@mhs.mb.caCriteria for Memorable Manitobans | Suggest a Memorable Manitoban | Firsts | Acknowledgements

Help us keep

history alive!