Manitoba Pageant, Winter 1970, Volume 15, Number 1

|

The founding of Riding Mountain National Park, as told herein by Charles T. Thomas of Portage la Prairie, the sole surviving member of the executive committee of the Riding Mountain Association, is a story fraught with problems, frustrations, and ultimate triumph. It is a recital of events in which dedication and perseverance played important roles in bringing a vision to reality.

Inasmuch as the cultural and recreational mores of a people are an integral part of their history, the story of the founding of the park has a proper place in Manitoba Pageant. To fully understand the Roman people, particularly their decline and fall, we have to know about their social customs and recreational pursuits. When these things became rotten, they hastened the moral decay of the people and the dissolution of the empire.

Furthermore, to fully understand the character of the British people, we have to know about their involvement in politics, wars, discoveries, inventions, industrial progress, and religion; but as well, we must know about their great love of sports and about their participation in such out-door events as games, races, fairs, pageants, festivals, boating, bathing, hunting, and fishing.

In the course of time these leisure-time activities were transplanted in colonies all over the world. Their planting in this province by the early agricultural settlers and town dwellers shows the strong bent of these people for outdoor recreation. In the late 1880s, before there were roads between Winnipeg and Lake of the Woods, when the only line of communication between home and cottage was the railroad, citizens of Winnipeg founded summer resorts at Keewatin, Rat Portage, Coney Island, Devil's Gap, and Clearwater Bay. The developments at Grand Beach and Winnipeg Beach also preceded the building of roads to the sites.

In the case of the country people, some of them had picnic sites, camp grounds, and summer places on various lakes and rivers throughout southern Manitoba before the turn of the 20th century. Some of these were situated at Max Lake in Turtle Mountain, at Rock, Pelican, and Killarney lakes, at Oak Lake, at the Little Saskatchewan near Minnedosa, at the great oxbow of the Assiniboine at Portage la Prairie, and at the Delta Beach on Lake Manitoba. At all these places, first used only for picnics, fishing, and shooting, summer homes were later built, and here the pattern of outdoor recreation in Manitoba became established at an early date.

In this sense, in the wide perspective of social history, the founding of a national park in Manitoba is a significant expression of the character of the people, particularly of those who led the enterprise to a successful conclusion. As such, this story is justly presented.

Riding Mountain was made a Timber Reserve and withdrawn from settlement by the Lands Branch of the federal government in the closing years of the 19th century. In 1906, under the Forests and Parks Act, the area was transferred from the Lands Branch to the Forestry Branch of the Department of the Interior. At this time its designation was changed from a Timber Reserve to a Forest Reserve in which hunting and fishing were allowed except for an area of 216 square miles which was set aside as a game preserve. A four-foot line, cut around the area to mark the boundaries in 1912, was redefined in 1923. The first lots were surveyed in 1915. Mr. L. B. Gusdal filed on the first building site; Mr. J. H. Baker of Kelwood opened the first place of business in 1925.

In 1927 the idea of creating a National Park in Riding Mountain was first conceived in the minds of D. D. McDonald and J. N. McFadden, both citizens of Dauphin. Mr. McDonald was a Mayor of Dauphin and during the period in which negotiations were going forward for the establishment of a national park, he was Secretary of the Union of Manitoba Municipalities. Mr. McFadden, a barrister, had a wide interest in local organizations.

As a result of the original inspiration and subsequent collaboration of these two gentlemen, an inaugural meeting in connection with a proposal to establish a national park at Riding Mountain was held in the Town of Neepawa on 6 October 1927. Delegates to the meeting had been invited to attend from all areas of the province and some eighty representative citizens answered the call. The principal outcome of this meeting was that the delegates voted to form a Riding Mountain Association to press for a national park. It was only fitting that Mr. McDonald and Mr. McFadden should become president and secretary respectively. In addition, an executive committee of some eleven or twelve representative citizens was elected. This committee became the driving force behind all subsequent efforts to obtain a national park in Riding Mountain.

The writer was a charter member of the Riding Mountain Association. Moreover, insofar as extensive enquiry reveals, he is the sole survivor of that group. On these two counts it therefore seemed wise to put down a few observations about these men and about the work they did which led to the establishment of Riding Mountain National Park. This particular project has not been done before, and so, on the grounds of original recording, it may also have some merit.

The members of the Riding Mountain Association came from many widely scattered parts of the province. Michael Baroni, a hotel proprietor, was from Neepawa. J. L. Cowie, a newspaper man from Carberry, subsequently became King's Printer for Manitoba. James Allison Glen was from Russell. He was originally MP for Marquette and later Speaker of the House of Commons. Marcus Hyman, a member of the provincial legislature for Winnipeg, took a keen interest in the project. He was the only representative from Winnipeg in the Riding Mountain Association. David L. Mellish of Pipestone, Reeve of Pipestone Municipality, went on to become Chairman of the Municipal and Public Utilities Commission of Manitoba. Roderick McAskill, a businessman of Gladstone, was for some years mayor of that town. He was also widely known as a curler. William A. Oglesby represented Brandon. He was a merchant and alderman. The writer, a barrister at Glenella, was also secretary-treasurer of the Municipality of Glenella. Last, but by no means least, the Town of Dauphin, besides having President McDonald and Secretary McFadden on the executive, had W. J. (Billie) Ward, MP for Dauphin. He and the Hon. J. A. Glen were our influential voices in Ottawa.

Early ungraded road - merely a clearing through the bush - in the Wasagaming town site, Clear Lake, Riding Mountain

Vicissitudes of travel within the Wasagaming town site, Clear Lake, Riding Mountain, circa 1920

As mentioned earlier, there may have been twelve men on the original committee, but the names of eleven only are given in the foregoing paragraph. This is because I am dependent on memory, the first minute book having been (presumably) destroyed in 1957. In consequence of there being no original source of reference to which one may turn for verification, a doubt remains. However, insofar as memory serves me, there were eleven men on the original committee.

In any event, shortly after the election of the committee, it went into action and in the course of time recruited support from some eighty different organizations. A thousand citizens became intimately involved in the work to obtain a national park for Manitoba. The members of the provincial legislature also had to deal with this project and declare themselves. Many citizens expressed their approval. Some raised objections. Still, throughout all the negotiations, the committee remained active and optimistic, and it was the sole coordinator of all the diverse endeavors in support of the park.

Despite the enthusiastic support for the Riding Mountain project, opposition to the idea was substantial. This stemmed almost entirely from the fact that an alternative site in eastern Manitoba [now the Whiteshell Provincial Park] found great support among Winnipeg people and residents of the eastern and southeastern portions of the province. In the face of this division of opinion, the Riding Mountain project lay in doubt for quite some time. Finally, however, the factors which tipped the scales in favor of the mountain site were the excellence of the Riding Mountain Association organization and the steadfast support it received from the citizens and their leaders in the western and central portions of the province.

The advocacy of the eastern site as opposed to that of the west-central site is clearly seen in the news item which reported on a meeting of a sub-committee of the Winnipeg City Council, March 5, 1928. "The sub-committee, under the chairmanship of Alderman R. H. Pulford, heard representations from the Manitoba Motor League, the Manitoba Government, the City of St. Boniface and various Service Clubs. Ace Emmett of the Manitoba Motor League outlined the advantages of the eastern site. The Honourable R. A. Hoey supported him. Elswood Richards took the other side and pointed out that the Riding Mountain site was much more suitable. He contended that a chance should be given to the Riding Mountain Association representatives to state their case before the council committed itself. As the Riding Mountain district was not sufficiently represented at the meeting, this argument prevailed, and the matter was laid over for a week." (Winnipeg Free Press, 6 March 1928.)

About this time I was delegated to meet with Alderman Pulford for the purpose of drafting a resolution for presentation to a subsequent meeting of the sub-committee of the Winnipeg City Council. The outcome of this particular meeting is lost to memory, suffice to say, however, the Riding Mountain Association had ample representation at the next meeting of the sub-committee.

Prior to this meeting, the Minnedosa Tribune, on 16 February 1928, had this to say about representations for a national park in Riding Mountain. "Dr. E. J. Rutledge, MLA for Minnedosa, made a motion in the House that a National Park for Manitoba should be established in the vicinity of Riding Mountain. An amendment was moved by Mr. McKay and seconded by Mr. Breakey, 'that in the opinion of this House a National Park should be established in the vicinity of Riding Mountain as well as in the eastern part of Manitoba.' The amendment carried. Mr. Pratt of Birtle apparently did not vote at all. Mr. Wolstenholme of Hamiota Riding voted against the motion and in favor of the amendment." The Tribune then proceeded to indignantly record: "It does seem a pity that when local organizations work so hard and spend their own money in order to organize a movement, members of parliament representing the same district should fail to appreciate the significance of the movement, but practically vote against it in favor of such a dubious location as the rock-bound eastern boundary of Manitoba."

The Honourable Charles Stewart, Minister of the Interior, addresses a gathering at Clear Lake on the prospects of developing a playground at Riding Mountain - 16 August 1928.

The Kamsack Cyclone, 9 August 1944, played havoc in the vicinity and, miles away at Riding Mountain, tossed this large conifer on the author's cottage.

From the foregoing account it would appear that the Riding Mountain project did not have the unanimous support of its own western citizens. But the park committee, supported by its numerous loyal backers, did not give up. The authorities in Ottawa were bombarded with resolutions, letters, and telegrams from more than eighty organizations. Members of Parliament were also spurred on, and the measure of their support was summed up in the Winnipeg Tribune of 18 February as follows: "Nine Manitoba M.P.'s are in favor - sign petition - four others signify support - likely that Riding Mountain site will be selected." This memorial was circulated by W. J. Ward, M.P. for Dauphin.

In its issue of 20 February, the Winnipeg Free Press observed: "All Manitoba M.P.'s excepting Dr. Bissett of Springfield sign petition in favor of Riding Mountain. There has been a steadily growing opinion among Manitoba Members that the proposed national park in Manitoba should be located in the Riding Mountain rather than in eastern Manitoba ... The officials of the Parks Branch have hitherto favored the latter site ... It would now appear that the final choice would fall upon the former. A petition by W. J. Ward, M.P., signed by every rural member of Manitoba excepting Dr. Bissett has been presented to Honourable Charles Stewart, Minister of the Interior. No official decision has been made."

From these press excerpts it can readily be seen that the project was no push-over. Indeed, according to the Dauphin Herald of 2 May 1929: "There is to be no national park in Manitoba, but rather, a recreational area in Riding Mountain. In addition, an article in the Winnipeg Tribune about the same time, entitled "Dallying with National Parks," went on to say: "Manitoba dallied too long in the national park question. Two years ago the federal government was prepared to set aside immediately an area as a national park and develop it forthwith. Then the question of location arose and the federal government asked Manitoba for a clear cut decision. Federal Members could not arrive at a decision between the eastern section of the province and Riding Mountain. The provincial government offered no advice. Then the federal government undertook to inquire into both locations and reached the decision that neither site was altogether suitable. Instead, a recreational area is to be established in the Riding Mountain area. So Manitoba gets no park at all. Agreement with the province and a clear cut decision appears to be what the federal government wants."

On 8 August 1928, the Winnipeg Tribune concluded an article on the impasse in the park question by reporting: "Without some outside arbitrator it is going to be difficult to get a decision of any kind. The Tribune has suggested again and again that the permanent officials of the National Parks should be consulted as final referees between the eastern and western locations and their finding, whatever it may be, cheerfully accepted. No one else has the knowledge and impartial position that would make such a finding really authorative. A year later the Tribune again raised hopes by reporting: "The Department of the Interior is still considering the question of a national park for Manitoba, the two locations first talked of are still being watched."

Commemorative cairn on the lakefront, Wasagaming, Clear Lake, Riding Mountain National Park.

Clear Lake, Riding Mountain National Park, looking west from a site near the golf clubhouse.

Despite all the bickering, on 16 August 1928, the Riding Mountain Park project took two steps forward - and one step back. The park committee succeeded in having the Minister of the Interior personally inspect a small portion of the proposed site. On the previous day the Brandon Sun reported: "Minister will see beauties of big park. Clear Lake will be visited Thursday by the Honourable Charles Stewart. The Minister of the Interior will be guest at a basket picnic." I was present on this occasion and still have in my possession a snapshot of the Minister addressing the assembled crowd.

It is my conviction that the Minister there and then promised, not a National Park; not a park at all, but "a playground for us and our children and our children's children." But newspapers of the time called it a recreational area. The Dauphin Herald of 2 May 1929, said flatly: "Recreation Area to be created in Riding Mountains. There will be no national park in Manitoba according to a decision reached within the past few days by the Interior Department. The trained investigators sent out by the department last spring went over both areas [eastern and western] very carefully and reported unfavorably in both cases. These reports, however, favored the creation of some kind of public playground in Riding Mountains. This [public playground] is a hybrid entity ... It has been decided to centre the activities at Clear Lake." This article carried the sub-heading: "Dauphin Is Satisfied."

The writer does not know what clinched the decision in favor of a park in the minds of the mighty. Perhaps information exists in Ottawa which shows why a favorable opinion was reached. In any event, the Minister states that it is not proper policy to make the surviving departmental files available for public inspection at this time, (almost forty years after the park was created).

Following the visit of the Minister of the Interior to the proposed park site in Riding Mountain, the committee and many of its supporters continued to be dissatisfied with the small public playground concept advanced by the federal government and which seemed to satisfy the Dauphin Herald. Nonetheless, hope still held fast, faith persisted, and pressures were still being applied by the committee for the creation of a large national park. Then, out of the blue, as it were, this persistence found its goal in the sudden announcement on 25 January 1930, that a national park would be established at Riding Mountain embracing the whole escarpment.

A partial explanation for this sudden change of front by Ottawa may be found in the following factors. When the federal government originally offered a small recreation area as a public playground, the park committee countered with two arguments. First, that it would not be advisable, upon the transfer of natural resources to Manitoba, to have a divided authority within Riding Mountain. It was an entity and should be treated as such.

Highway to Clear Lake (1933) - from souvenir pamphlet issued by the Department of the Interior, to mark the official opening of Riding Mountain National Park, 26 July 1933.

Descendants of these monarchs of the plain (1933) still roam the range near Lake Audy, Riding Mountain National Park.

Secondly, that one of the results of having a national park established would be that by the same token a game preserve would likewise be created and that the small area originally offered would not effectively serve this purpose.

After the establishment of Riding Mountain National Park, the committee continued to function intermittently in an advisory capacity. Several meetings were held at Neepawa with Mr. James Smart, the first acting-superintendent. Mr. Smart had been a forest inspector in Alberta and upon the creation of Riding Mountain National Park had been transfered to Manitoba. Exceptionally capable and cooperative, he was pleased to carry out some of the committee's suggestions. The committee quickly realized, however, that Mr. Smart did not need its assistance or advice and with some regret began to think of disbanding.

At the final wind-up of the Riding Mountain Association, the members and their friends met around the festive board within the park itself. There were many present to witness the demise. Congratulations were tossed about ad nauseum. The lethal motion to disband was put and carried and a heavy pall of silence fell over the whole gathering. On this day I was accorded a signal but unorthodox privilege, that of countersigning with the president a cheque in favor of the secretary covering the small bank balance which remained in the association's account. There was now no need for further funds; the secretary had given service away beyond the call of duty, and thus his work was recognized.

In the early days, prior to 1930, getting into the park was quite a precarious undertaking. During wet weather there were many mud holes and beside each of these some well intentioned fellow, or perhaps a joker, had placed crude wooden signs exhorting the passing motorist to dump in a bucket of sand, or at least a shovelful, to help fill the numerous sodden depressions. However, from 1930 onward the situation began to improve. Public interest in the park grew by leaps and bounds. It became a place to visit on Sunday afternoons or holidays. Every week during the initial stages of development there was something new to see.

One particular Sunday afternoon my wife and I were intrigued by an extensive series of clearings in the bush which had not been there before. They were irregular in shape, with little or no pattern, and were, as we found out later, the clearings for the fairways of an incipient golf course. Strolling along one of these clearings we came upon a group of people who were listening to one of their number as he talked to them and pointed out the various physical features. The speaker, O. E. Heaslip of Dauphin, was slated to become the first superintendent of the park, but before his appointment was confirmed a change in government took place and his appointment became politically untenable. Mr. Smart, the acting superintendent, then received the appointment as first superintendent.

With the creation of the park in 1930 and with a change of government in Ottawa shortly thereafter, the in-fighting for the appointment as superintendent of the park quickly developed. Through the party grapevine it was learned that there were at least six applicants for the position, some of whom I knew quite well. Perhaps in-fighting is too harsh an expression. Let us soften it to sparring or jockeying. I cannot recall that I ever applied for the job as park superintendent, but someone who ought to know claims that I did.

To my mind the position, at that time, carried with it several major disadvantages. To begin with, some antagonism to the formation of the park had developed among those who were accustomed to fish and hunt therein at will. Some others feared that the privilege of getting out firewood and timber would be restricted if not cut off altogether. It was also rumored that there would be entrance fees and permits and other red-tape. In addition, it was feared by some officials that fires might be set off in spite by some disgruntled individuals. Indeed, during the first few years, whether by mischance or intent, a large number of fires did break out in Riding Mountain National Park.

This wasn't a pleasant situation for a park superintendent to face, and to be saddled with the responsibility for fighting the fires was a serious business. Furthermore, the education of small children in the rudiments of conservation would likely be a problem for some years to come. Finally, the position of park superintendent, to be properly administered, would require permanent residence in the park all year round. Until such time as the roads were put in much better condition than they were, this would mean almost virtual isolation during the spring and winter months.

The Great Depression was a terrible thing, but it was a fortuitous event for Riding Mountain National Park. To deal with the acute unemployment problem and to grant some small measure of relief, large work camps were quickly established in the park. An army of men desperately in need of sustenance began to pour in. The wages, such as they were - all that could possibly be spared from an attenuated federal treasury - were $5.00 per month per man together with board and bunk. A man with a team could command $8.00 a month.

As secretary-treasurer of an adjacent municipality, I had some part in the administration of relief, and it runs in my mind that over the depression years I assisted in sending into the Riding Mountain relief camps some 187 men. Whatever judgement one may pass on the government's handling of the Great Depression and of its establishment of relief camps, the fact remains that because of the great amount of labor available and the necessity of finding a place to employ it, the development of Riding Mountain National Park, the opening up of its natural beauties and the building of man-made facilities, proceeded at a phenomenal rate.

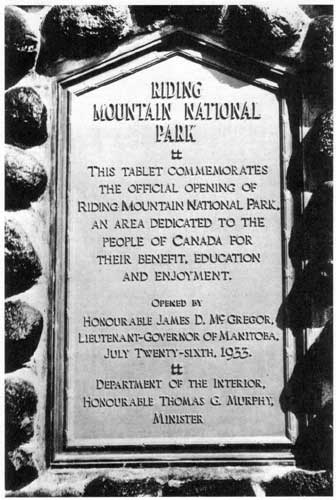

The formal opening of the park took place on 26 July 1933, some three years after its creation. The opening was arranged by the Honourable T. G. Murphy, and on his invitation the Honourable James D. McGregor, Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba, presided over the dedication ceremony. Speakers included the Honourable John Bracken, Premier of Manitoba; the Honourable J. T. M. Anderson, Premier of Saskatchewan; J. L. Bowman, M.P., (Chairman), Colonel H. A. Mullins, M.P., and Mr. W. C. Wroth, President of the Union of Manitoba Municipalities. Manitoba cabinet ministers attending were W. R. Clubb, Minister of Public Works; W. J. Major, Attorney-General; J. S. McDiarmid, Minister of Mines and Natural Resources. W. H. Burns, M.P. and Errick Willis, M.P. also attended, together with Mayor S. E. Snively of Duluth and Mayor Ralph Webb of Winnipeg. The ceremonies (even at this early date) were broadcast through the courtesy of the Manitoba Telephone System in collaboration with the Canadian Broadcasting Commission.

This important ceremony is also noteworthy, at least in my own mind, because of a glaring omission. Not a single member of the Riding Mountain Association [the founding committee] was seated on the platform or mentioned in the various speeches during the dedication ceremony. A similar omission rose again a quarter of a century later, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the opening of the park, when a letter to me from the widow of one of the most active founders read in part: "I attended the anniversary and watched it from the fringe of the crowd." Sic transit gloria mundi.

The creation of Riding Mountain National Park, in the face of great obstacles and much regional and partisan opposition, was made possible through the dedicated work and persistence of the Riding Mountain Association. But there is not a single word in the park itself or in any other place to acknowledge the work of the founders. It is therefore my suggestion that on the stone cairn which already stands in the park, marking the dedication, another plate be added containing the names of the committee - the men who fought the issue through to a successful conclusion. A logical time for this long overdue tribute would be during Manitoba's centennial year.

One of the earliest references to Riding Mountain is recorded in the very first sentence of the first paragraph of Alexander Henry's journal. Henry writes: "Autumn. 1799. While building at Riviere Terre Blanche [Whitemud River], near the foot of Fort Dauphin [Riding] Mountain, my Russian sheeting tent was pitched in a low place on the lower branch of the little river, sheltered from the wind, among some tall elms and oaks." - The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry, p. 1.

Later on, the note by Elliott Coues, covering Henry's departure by cariole from Pembina Post on 4 January 1803. reads in part: "Dauphin. as a name of various things in this [Riding Mountain] region, dates hack to Verendrye, 1741. Fort Dauphin nit., or Dauphin mts., is or are the general and extensive elevation now called Riding nit., W. of Lake Manitoba." - Ibid, p. 207.

On 14 July 1806, after heading northwest through the Tiger Hills, Henry wrote: "From the summit of these high, barren hills we had delightful views. In some low spots were clusters of poplars; to the north we could see the Assiniboine, N. of which we could trace the course of Rapid [Minnedosa River], which comes from the Fort Dauphin mountain." Ibid, p. 305.

Alexander Henry, the younger, nephew of Alexander Henry, the elder, entered the service of the North West Company sometime in the 1790s. In 1800 he was given command of Pembina Post at the fork of the Red and Pembina rivers. In the following eight years he made many trips from this post to the Assiniboine and Souris country - and beyond. He probably knew southern Manitoba better than any other fur trader of his time. Besides his extensive observations about the Red, Pembina, and Souris valleys, the Carberry Sand Hills, and the Tiger Hills, he left, well in advance of the trained geographers and scientists, quasi-scientific notes about the origin of the marshes below Riding Mountain.

Another early reference to Riding Mountain [by inference or association] was made by John Tanner, probably during the first decade of the 19th century. The Place Names of Manitoba, referring to Riding or Dauphin Mountain, says: "Riding or Dauphin Mountain `may be the hill referred to by John Tanner as `naowawguncvadju' - the hill of the buffalo chase near the Saskawijewan [Minnedosa] River.' "

John Tanner was born on his father's farm in Kentucky about 1780. Nine years later he was captured by Indians and for thirty years thereafter lived with the Ojibwa. As this tribe moved westward from the north shore of Lake Superior, through the Whiteshell (in search of wild rice beds), and onward to the Souris and Minnedosa valleys, Tanner went with them and lived among them. The former name of the ford at the crossing of the Little Saskatchewan River at Minnedosa was Tanner's Crossing.

The first comprehensive observations on Riding Mountain and the circumjacent land were made on 10 October 1858, when Henry Yule Hind, head of the scientific division of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition, after having traversed the land between Lake Dauphin and Riding Mountain, committed the following notes to his journal:

"Soon after breakfast, we arrived at a steep embankment about 70 feet high, which formed the termination of a plateau about a mile broad, covered with small aspens, and threaded with Moose paths. The plateau ascends very gradually and is abruptly bounded by a hill bank, from which a broken hilly tract rises towards the escarpment, which forms the eastern limit of Riding Mountain. This broken tract is covered with aspens and spruce of large size, especially in the hollows. We crossed the beds of two or three streams, which flowed through deep gullies to the plain below. So far, the soil consisted of drift clay with many large boulders in the beds of the rivulets; but at an altitude of about 400 feet above Dauphin Lake we arrived at a cliff-like exposure of Cretaceous rocks, through which a stream had cut a channel 70 to 90 feet deep. These rocks seemed to form the boundary of a third plateau, on which were numerous conical hills consisting of gravel and boulders of unfossiliferous rocks. The stratification appeared to be nearly horizontal, with a very slight dip to the south-west. Although a careful search was made for organic remains, very few were discovered. These were identical with those found on the Little Souris, and in every particular except the occurrence of bands holding Inoceramus, the rocks of Riding Mountain resembled the exposures on the Little Souris. The layers containing ferruginous concretions [resembling iron rust in color, relating to, or containing iron] were found, as well as a soft thin band from which the Indians make their pipes. The total thickness of the exposure exceeded 100 feet .

Then there follows the well known passage: "The view from the summit was superb, enabling the eye to take in the whole of Dauphin Lake and the intervening country, together with a part of Winnipeg-osis Lake. The outline of the Duck Mountains rose clear and blue in the north-east*, and from our point of view the Riding and Duck Mountains appeared continuous, and preserving a uniform, bold, precipitous outline, rising abruptly from a level country lying from 800 to 1000 feet below them. The swamps through which we passed, were mapped in narrow strips far below; they showed by their connection with the ridges, and their parallelism to Dauphin Lake, that they had been formed by its retreating waters. The ancient beach before mentioned, as extending far to the north and south, could be traced with a glass, by the trees it sustained, until lost in the distance; it followed the contour of the lake, whose form was again determined by the escarpment of Riding Mountain." - Reports of the Progress Together with a Preliminary and General Report on the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition; H. Y. Hind, Toronto, 1859, pp. 96-97. (*west?)

In the days of the fur trade, the streams that flowed down from Riding Mountain to the extensive marshes below, provided the necessary fluctuations in volume - the freshets of springtime, the periodic flushes during times of heavy rainfall, and the ebb-flow of high summer - the changes in water level which are essential to the preservation of ideal feeding and breeding conditions in a marsh environment.

So it was that traders of both the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company referred to the Dauphin, Riding Mountain areas as good "Rat Country."

No wonder, therefore, that successful traders like Alexander Henry, the younger, Daniel Williams Harmon, and John Tanner, maintained wintering posts in this country and zealously sought muskrat skins from the resident Cree and Saulteaux.

The whole western flank of the province, from the Antler Creek area in the extreme southwest, northward through Riding, Duck, and Porcupine mountains, through to the Pasquia Hills and the great Summerberry Marsh at The Pas - all this was [and still is] good rat country. The list of licensed traplines, issued by the Manitoba Department of Mines and Natural Resources, contains the names of farmers who make good supplementary incomes from trapping muskrats. One farmer of the editor's acquaintance has made a rather substantial income for twenty-five years from trapping muskrats on the marshes and feeder streams south of Riding Mountain.

Today there are fewer marshes than once there were about Riding Mountain. Drainage ditches, taking the run-off to streams and lakes, and the extensive clearing of bush and scrub land [the great retainers of sub-surface moisture] have substantially reduced the marsh acreage. There are, nonetheless, plenty of indications along the borders of streams which flow from Riding Mountain that marshes, before the days of agricultural settlement, were large and widespread, cradled, as it were, between the ancient beach ridges of glacial Lake Agassiz, of which seven may still be traced between the eastern escarpment of Riding Mountain and the western shore of Lake Manitoba.

One old pamphlet, issued by the National Parks Division, Ottawa, as a tourist promotion piece, says that Riding Mountain takes its name from the Riding Trails of the Indians across the escarpment. This seems to be a rather tenuous source in which to root the name, for nowhere else (to the editor's knowledge) in the early journals of the west does the term Riding Trails occur.

However, the following note from Hamilton's "In The Beginning" suggests a source, albeit by transposition of terms: "Pitching Tracks - The origin of this term is obscure. J. B. Tyrell in his reports refers to these tracks as rounded ridges of gravel known to the Indians as pitching trails. These appeared to have been used by the Indians as they were usually above the surrounding terrain in the area of Riding Mountain and Duck Mountain. They were apparently the shorelines of glacial lakes. Professor Henry Yule Hind climbed up from Mossy River on one of these tracks to the Riding Mountain escarpment [in 1858] but he does not explain what they were. Professor W. L. Morton in his book, Manitoba: A History, has a map showing pitching tracks but he does not explain the term.

It is believed the term refers to the trails used by the Indians in their movements alongside which they could pitch their camps. Certainly in the area mentioned, [Riding Mountain and Duck Mountain] they could have been the only dry ground fit for [riding] and camping throughout an area where there was much swamp."

"Riding Mountain National Park has a setting and character unique for any prairie province. Situated on the fringe of the Great Plains region that extends northward from the Mississippi Valley into Central Canada, it occupies the vast plateau of Riding Mountain which rises to a height of 2,200 feet above sea-level. On the east and northeast, the park presents a steep escarpment, towering nearly 1,100 feet above the surrounding country and affording magnificent views of the fertile plains below. Sweeping westward for nearly 70 miles, the park contains an area of 1,148 square miles, is heavily forested and set with numerous crystal lakes, some of which are several miles long."

"The origin and early history of Riding Mountain are of interest, for many of its natural features were shaped by the great glaciers of the ice Age. The steep escarpment itself is mainly the result of pre-glacial erosion, and later, with the surrounding country, lay under an immense sheet of ice. Evidence of glacial movements remain in the depressions now filled by small lakes and by moraines and boulders that are found in many parts of the park. The ridges are believed to have been Indian high-ways . - Riding Mountain National Park, National Parks Branch, Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources, Ottawa, Queen's Printer, 39-488-EL/96.

Probably the earliest inferential reference to Riding Mountain is the one expressed by W. L. Morton as follows: "In 1741 Fort Dauphin was built to serve the Mountain Crees, the Indians of the beaver-terraced escarpment west of lakes Manitoba and Winnipegosis - Manitoba: A History, p. 33. The source of Mountain Crees is Burpee, Journals of la Verendrye, pp. 378-9.

These fine conifers are typical of the arboreal cover of Riding Mountain. From such a stand on the western cuesta, the sternwheeler Northwest, on her maiden voyage on the Assiniboine, 20 May 1881, took down to Winnipeg a load of timber which sold for $22,500 cash, almost enough to recover the entire cost of the vessel - $27,000.

The bowl of this Indian pipe is made from the same sort of rust-colored rock as Hind discovered at Riding Mountain.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Riding Mountain National Park Monument

Page revised: 16 July 2011