by Roy W. Brown

Brandon, Manitoba

Manitoba Pageant, Volume 24, Number 3, Spring 1979

|

History isn’t just something that happened hundreds of years ago, miles away. Manitoba is filled with interesting tales of yesterday. I hope you enjoy this one about one of the riverboats that plied the Souris River between Napinka and Scotia, North Dakota and was later used on the Assiniboine in the Brandon area.

In 1969, the writer was engaged by the Brandon Chamber of Commerce as the Assistant Manager, charged with coming up with some historic event that could help in promoting the centennial year program in 1970. My thoughts turned to the early riverboat days when flat-bottom stern and paddle wheelers brought people, implements and animals to the outpost of commerce in Grand Valley—Brandon’s antecedent village. Research revealed that after the original Prairie Navy had been displaced by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1881, a sidewheeler was used in building the Grand Trunk Railway bridge three miles downstream from Brandon.

My first task, of course, was to find out who had built the boat. Finally, after a great deal of research I got a lead from a local man who told me that the engineer of the craft at the time the boat had capsized was still alive and was at that time living in Dauphin. What a surprise to discover that I had known the man for 40 years!

I contacted Mr. Art Mansoff and he gave me some of the boat’s history. He made a tape recording and sent it to me. The taped story revealed that the remains of the Assiniboine Queen might be found approximately 300 feet downstream from the north abutment of the bridge.

Mr. Mansoff told me that a man from Shelburn, Ontario had built the boat in Coulter about 1908, and that I could likely find many people in the community who would remember the Ontario-born Irishman who had come to Coulter to help build the CPR, and had ended up building a riverboat. Indeed, there were many who remembered him.

Hunt Johnston Rolston Large was born in Shelburn, Ontario, on 17 June 1876, and died 10 April 1947. According to information received from his son William in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, he came west at the turn of the century. He probably came with the CPR as it moved west along the southern route through Waskada, Coulter and Lyleton, between 1900 and 1903. In any case, he did start a business in the village of Coulter under the name South Antler Steel Works. His business cards and announcements indicate that he ran a general repair and machine works, making many different types of farm implements and small items such as wiffle trees, double trees and cement mixers.

According to several pioneers who remembered Captain Large, he was very well liked. And several people with whom he had had business dealings—and never paid—still had a good name for the kind-hearted man who sang at his work six days a week and even on Sundays, in his workshop next door to the Coulter church. It was the noise from his shop that finally resulted in a visit from the minister who had been asked by the congregation to have a chat with Rolston about the noise during church services. The minister had to report to the elders of the church that he had made a mistake by visiting Captain Large because he knew more about the Bible than he did. However, the machines remained silent thereafter.

Rolston Large was a genius, in his own right. He possessed a wonderful personality and much talent. He was a master mechanic, a steam engineer, an inventor and a good musician. He could also type and operate a telegraph key.

According to one news report published in the Melita newspaper, Rolston was given credit for repairing stranded automobiles because of their mechanical failures. It appears that an American visitor to Coutler in 1909 was helped by Rolston when his “new fangled horseless carriage” wouldn’t run.

Many people have asked, “why would a man with such talent build a large riverboat in a prairie village”? It was the challenge. Rolston could probably envisage himself aboard his own riverboat singing songs and partaking of the “goodies” brought on board by the passengers. (And research found this to be true).

The Empress of Ireland was far from being a handsome craft, but it was quite seaworthy. The boat was built near Large’s shop with the aid of people from the community and the experience of two carpenters Andy and William McKague. Large, somehow, procured an old CPR boxcar, and the plank flooring from it was used for the bottom of the boat. An old house was dismantled, and the dimensional lumber from it was used for the superstructure. Her engines were two Sawyer-Masseys which had been removed from old steamers by Rolston. The two large metal paddle wheels were rebuilt in Rolston’s shop from tractor traction wheels.

The Empress was 66 feet long and about 10 feet in width just narrow enough to pass between the pilings of the CPR bridge that spanned the Souris River, on her trips to Scotia, North Dakota.

There were many people who laughed at Rolston’s plan to build the riverboat. And one skeptic asked Large if he thought the “darn thing” would float. Large painted a water line on the hull and the skeptic was quite surprised to see the craft draw just enough water to meet the line; Large had no doubt whatsoever about the seaworthiness of his Empress of Ireland.

It must be remembered that Large built his “dream boat” long before the advent of electric arc and acetylene welding. The workmanship in the paddle wheeler, and other metal components, was the work of a master tradesman, the quality of which would be difficult to find today.

I obtained a great deal of information from a lady who had known Captain Large—Miss Margaret Elliott of Melita. It was from her that I got the address of William Large, one of Rolston’s sons who lives in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. She also provided me with the original passenger tickets, Large’s business cards, and photographs of the riverboat.

The Empress of Ireland was launched in 1909 at the confluence of the Souris and South Antler rivers north east of Coulter, which has been recently designated as a pioneer park.

In 1910 Captain Large decided to move his craft to Brandon where there was a better chance to make money, by operating excursion trips on the Assiniboine. The boat was cut in two pieces and loaded on two flat cars at the CPR station in Coulter. I haven’t been able to find out how it was unloaded and transported to the Assiniboine River, but Rolston would easily solve that problem, I’m sure.

Captain Large opened a machine shop at 347-18th Street north on the left bank of the Snye River, which at that time had its confluence with the Assiniboiune about one eighth of a mile away. He worked on the craft and after some remodeling, it was put into use again in July 1910 as a Brandon Fair attraction.

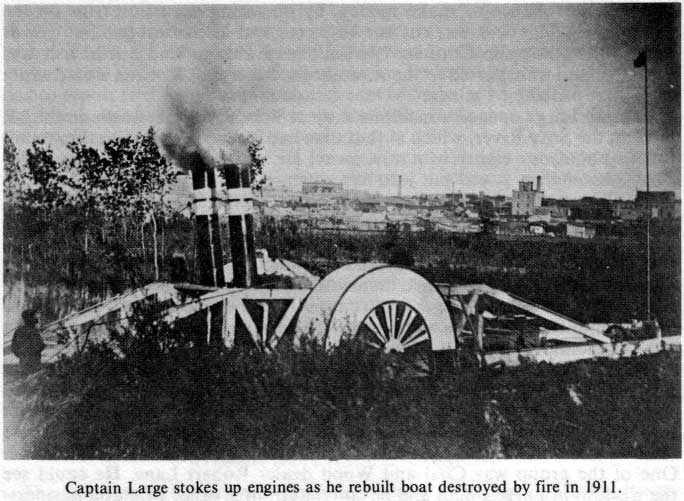

In the fall of 1911, the Empress was beached in the mouth of the Snye River and it was there that the superstructure was burned. And because Large owed a considerable amount of money, the wagging tongues blamed him for burning his boat to claim insurance money. However, I was able to disprove that rumor; a man who still lives in Brandon told me that he and his pal had broken into the cabin one night and were enjoying their first cigarette when they accidentally started the fire.

A lot of men would have quit right there and called it a day. But Rolston Large wasn’t a man who would toss in the sponge without a fight. He found a group of men who listened to his proposition to rebuilt the boat and convert it to a flat-bottom riverboat-freighter to transport coal downstream to where the Grand Trunk Railway planned to build a bridge across the Assiniboine. One of the group was Coal and Wood dealer Robert Lane. He could see the wisdom in Large’s plan and he convinced three other Brandon businessmen to join the enterprise.

So, once again Captain Large went to work in his shop to complete his dream. He rebuilt the burned hull and renamed the craft Assiniboine Queen. And, for a time, he may also have used the name City of Brandon. But, according to engineer Art Mansoff, she was using the former name when she capsized. (A search of the federal archives revealed that Large had never registered the boat under any name and had actually operated for several years without a licence.)

A torrential rain sent the old riverboat to the bottom of the Assiniboine in the spring of 1913. So Captain Large returned to the Coulter district and opened a machine shop on Waskada’s main street. When war broke out in 1914, he became a supervisor of the munitions factory, near Toronto. He eventually moved to Sault Ste. Marie and died there in 1940.

We finally found the remains of the old craft in the muddy bank of the Assiniboine exactly where Art Mansoff had said it might be. We recovered her two engines, the two paddle wheels and the anchor chains. One of her engines was made operable by Atom Jet Industries Limited as a Centennial project. The other engine was given to the Melita Museum. Other components were given to the Waskada Museum. One paddle wheel was placed in Coulter Park where the first launching had taken place. The other paddle wheel is on display at the junction of 18th Street and the Trans-Canada highway in Brandon, serving as a tourist attraction.

Since writing the prairie riverboat story, I have learned that Captain Large’s exploits with boats didn’t end when he abandoned his riverboat in the Assiniboine in the spring of 1913. Between the two World Wars, he recovered the remains of the famous HM Schooner Nancy from her watery grave north of Toronto, on Nancy Island.

According to the Captain’s son, Bill who still lives in Sault Ste. Marie, his father spent most of one summer exhuming the old Schooner which had been converted from a furtrader to a warship in the War of 1812. She was sunk by American gunfire in 1814.

Artifacts from the old Nancy may be seen in the Marine Museum of Upper Canada located in Exhibition Park, Toronto. A model of the old schooner is also on display in the museum.

Among the artifacts taken from the old schooner were large barrels of flour, a quantity of spirits, glassware and cutlery. And according to Bill Large, there was still a core of edible flour in the barrels of flour even though they had been submerged for over 125 years. The flour surrounding the core was as hard as cement.

Page revised: 6 September 2015