by F. Pannekoek

MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 34, 1977-78 season

|

The English-speaking folk of Red River looked with excitement and hope on the debates that surrounded the confederation of the eastern provinces. The Protestant Canadians, arriving in vocal and visible numbers in the 1860s to farm along the Assiniboine and to trade in the small village of Winnipeg, provided ample evidence of the vigour that the new connection would bring. All were anxious that union be effected quickly and quietly. Even the Protestant English-speaking mixed-bloods looked to Canada to pull Red River out of its morass of pettiness and squalor. When it became clear that Canada had secured the chartered land of the Hudson's Bay Company, most were ready, indeed anxious, to welcome the Canadian Governor, no matter how obnoxious he might be.

If the English-speaking half-breeds applauded the demise of old Red River with its peasant ways and too dominant patriarchs, the Catholic French speaking Métis feared its passing. It was increasingly obvious as the 1860s piled drought upon locust plague, that the hunt, the fisheries, the freight boat, and the cart would provide only the most meagre subsistence. The Métis merchants also feared that union with Canada, with its inevitable railroads and high tariffs, would spell the end to the profitable creaking cart trains to St. Paul and the Saskatchewan country. Equally important, union with Canada would mean a Protestant supremacy. The attacks on the Catholic faith by Red River Protestants in the 1860s had taught the Métis that Protestantism was the devil incarnate. The bigots of that faith sought to discredit the Catholics' Church, their morals and their lifestyles, and the Canadians who invaded the settlement in the later 1860s confirmed the fears of the Métis. The Canadian Governor-designate of the settlement was rumoured to have hanged at least two priests.

To the Métis hunters who wintered on the Saskatchewan plains, the debates that raged in Red River from the late fifties onward over the future of the North-West must have seemed irrelevant. It was their perception that the Company's despised and indifferent rule was finally at an end. Not all hated the Company with equal passion, but most recognized that the Company of 1869 was not the Company of legend. The great Chief Factors and greater Governors who had established the Company's reputation in the first instance had been replaced by a less inspired and more callous lot, and the decade of the 1860s saw mutiny after mutiny among the Métis manning the freight boats. The northern brigades were brought to virtual collapse and to the boatmen the insurrection in 1869 would be seen as the most successful mutiny of them all.

Each of the major groups that comprised Red River, then, had separate fears and unique motives for their involvement in the struggles of 1869. For the English-speaking mixed-bloods, it was a constitutional conflict gone away. From the 1850s onward, they applied pressure for a negotiated constitutional solution to the ills of Red River and its western hinterland. But then, when they were overwhelmed by the Métis initiatives, they resorted to military action if only to reaffirm the constitutional course. To the Red River Métis, however, 1869 was a defensive reaction arising out of their fear of the threat posed by a Protestant Canadian religious and economic supremacy; and to the Métis boatmen and winterers outside the colony, 1869 was the high point of a decade of protest.

The English-speaking of the settlement had wanted union with Canada as early as 1856. William Kennedy, an embittered ex-Company man, who had spent a number of years in the east, returned to the settlement that year to spearhead an annexation movement. Throughout the winter of 1856-57 meetings were held in the English-speaking parishes. By spring, Kennedy, whom many thought to be a secret agent of the Canadian Government, had manipulated the election of five members, including himself, to the Canadian legislature. The new members were already en route when news of Captain John Palliser's imminent arrival reached the settlement. It was thought that he had been empowered to negotiate the colony's future, and the five were recalled, [1] but Red River was to be disappointed in its hopes.

During this upheaval, the situation in the colony became exceedingly acrimonious when the pro-Canada movement split into a faction advocating crown colony status instead. Since crown colonies were not responsible for the salaries of their governors or the expenses of the military, many considered this to be the cheaper course. In the end, these arguments won out and the English-speaking united in 1862 to form a movement in favour of the crown colony option, particularly since the Canadian legislature seemed to ignore their every petition.

The head of the crown colony movement was the Rev. G. O. Corbett, a rather popular clergyman of the Church of England, who lived in Headingley. In 1862 Corbett was accused of attempting to perform an abortion on his maid servant, pregnant with his child, and the English-speaking mixed-bloods immediately assumed that it was a Company conspiracy to discredit the crown colony movement. When Corbett was found guilty and jailed, his supporters rioted. Corbett was reluctantly set free and the ringleaders of the riot jailed. Again the English-speaking mixed-blood horsemen rode to the jail to force the release of their brothers. [2] The situation had so deteriorated, and so little faith in the Company or in the Imperial Government remained, that the people of St. James and Headingley declared a "Provisional Government" in May 1863. [3] These parishes, along with Portage la Prairie, originally intended to secede from Red River and to form an independent colony subordinate only to the crown, but their original enthusiasm must have waned. What actually happened to the provisional government is not known; however, since it did not interfere with commerce or the government of the Upper Fort it was probably ignored, functioning in the end as little more than a parish council.

Whatever the outcome of the agitation of the 1860s, it is clear that the English-speaking half of the settlement was determined to effect a new political arrangement either within the Canadian union or as a crown colony. When news of the confederation movement in the Canadas drifted out to Red River in 1866, the English-speaking of the settlement seized the opportunity to negotiate with the colonies. As early as November, thirty-two of the settlement's most prominent settlers including Alexander Ross, Norman Kittson, Angus McBeth, John Pritchard and William Drever requested a public meeting to discuss the subject. On December 12, 1866, after much debate, a petition with two hundred signatures pleading for union was sent to the Imperial Government. It would not even be acknowledged until July 18. [4]

The movement's principal leader appeared to be Thomas Spence, an English-born storekeeper residing in Portage la Prairie, later to become clerk of the Manitoba legislature. He cultivated his Ontario contacts like Toronto M.P. Angus Morrison, in order to generate an interest in the Red River - Canadian union. [5] But there was little enthusiasm in Canada. Who was Thomas Spence and what and where was Red River? All the colony could do, and this was the advice from their Canadian sympathizers, was wait.

Events in Portage, a relatively isolated community with no real government of its own, pressed for more immediate and precipitous action. Riot and murder threatened to take over the settlement unless some form of government was imposed and in January 1868 the settlement resolved to proceed with the formation of yet another provisional government. A revenue tax was imposed and a jail was constructed. The new government's self-declared jurisdiction went from the 51st to the 49th parallels and from longitude 100 to the boundary of the Colony of Assiniboia. Thomas Spence served as the first President of the "Council of Manitobah," and was succeeded after the first year by a Mr. Curtis, who retained the position until the Riel interlude.

The Portage provisional government continued to press for recognition and Canadian union and while the English-speaking at Red River had developed cold feet, Portage chose to involve them in the scheme. In correspondence with the Imperial Government, Spence suggested that the Governor of Assiniboia, William Mactavish, be appointed the first Lieutenant Governor of the new territory. [7] This only prompted the Imperial authorities to chastise the Portage clique for its illegal usurpation of power. [8] Nevertheless the president and his council were so anxious for union that they continued to press Lord Monck, the Canadian Governor General, and Sir John A. Macdonald for action, albeit without any degree of success. [9] To most in Ottawa, Spence and Manitobah were the ludicrous accidents of an anachronistic frontier. They could be ignored until such time as they became useful.

The initial pressure for negotiating a union with Canada, then, came from the English-speaking mixed-bloods and white settlers at Portage la Prairie and Red River. They preferred to press for orderly constitutional change, and turned to the creation of provisional governments only in frustration. Given their fervent desire for union, the armed resistance of the Métis in 1869 must have seemed sheer madness. But if it was insanity, it was criminal insanity and it would have to be opposed vigorously and if need be with violence.

When Riel stopped the surveys, formed a National Committee, barred the highway to St. Norbert and seized Upper Fort Garry, the English mixed bloods were prepared to resist. They did so because they thought that union with Canada might be delayed again or that a new Métis-directed union might not be to their liking. In November and December of 1869 the mixed-bloods of St. Andrew's and St. Paul's had reached a decision - to retake the Upper Fort. By December 4 at least four hundred were ready to march. A lack of arms, ineffectual leadership, and a reluctant Protestant clergy, as well as an indication by Riel that he would attempt a "constitutional" solution to the impasse with Canada, ended the crisis.

Again in February 1870 the English half-breeds, this time the Portage la Prairie crowd spurred on by Canadians like Charles Mair, and the St. Andrew's group pushed by John C. Schultz, decided to bring about union with Canada by force. On February 10, sixty men left Portage and joined four hundred recruits from the lower settlements at St. Andrew's and St. Paul's four days later. The plan was to meet at Kildonan, seize St. Boniface, and bombard the Upper Fort. Again because of lack of weapons, ideas, and leadership, the movement failed. The English half-breeds were forced to negotiate over their demands for territorial governments and minimal taxation with the Riel faction who would obviously control the union deliberations with the Canadians.

The social and economic roots of the Métis involvement in the resistance are to be found in the changing environment of the 1860s both in Red River and in the interior. On the eve of the resistance the Métis were living in an increasingly smaller and more difficult world, well aware of the English hatred and uncertain as to the future. Even their own society had become more polarized since the 1840s, with more and more goods accruing to the wealthy merchant farmers of the parishes of St. Boniface, St. Vital and St. Norbert - a wealth based on the local grain market and on the lucrative St. Paul freight contacts with the Company and other private merchants. [10] Many of these teamster princes had accommodated themselves to the Company and sat on its Councils, while retaining pride in their heritage and culture. The majority of the Métis, however, squatted along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers and while the women tended the poor barley and potato patches, the men pursued the last of the buffalo, traded independently, or plied the Company's freight boats. The proceeds of the diminishing hunt and the Company's meagre wages could also be supplemented by the fall fisheries.

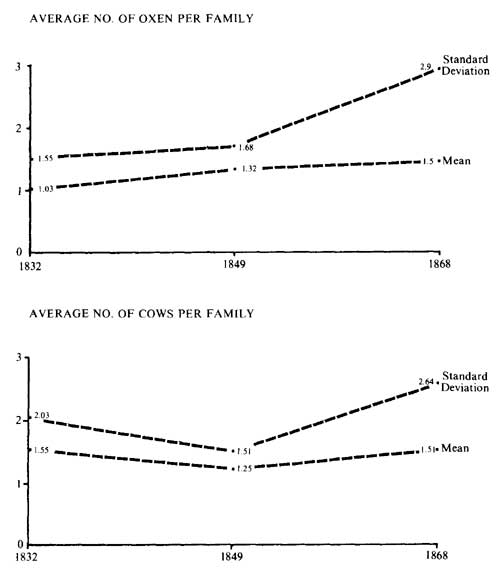

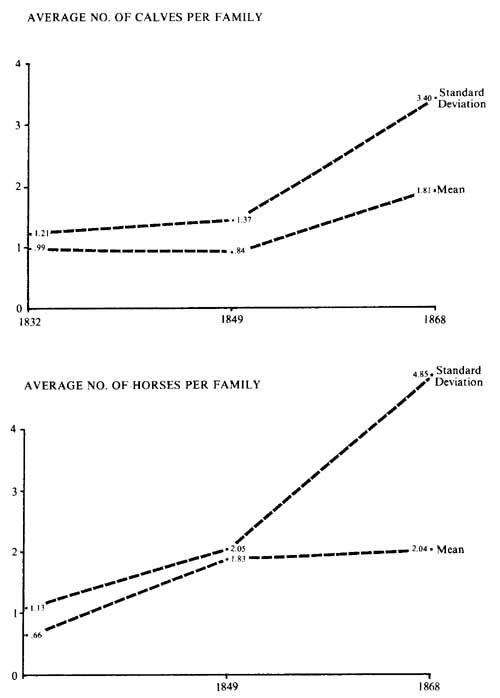

The Métis were in competition for the declining resources both of the plain and the river lot. To those who had seized the opportunity offered by free trade overland carting in furs accrued an increasing proportion of Red River's wealth. An examination of livestock holdings serves as an example of this growing concentration. The average number of oxen per family increased for example from 1.3 in 1849 to 1.5 per family in 1868, the average number of cows per family from 1.3 to 1.5, the average number of calves per family from 0.8 to 1.8, and the average number of horses from 1.8 to 2.0. But a disproportionate share of this new wealth fell to the merchant farmer. While in 1849 he rarely had more than the average number of horses, by 1868 he had at least twice as many. The same is true for oxen and calves. [11]

Wealth was particularly concentrated in the parishes of St. Vital, St. Boniface and St. Norbert. These parishes produced more than half of Métis Red River's grain and potatoes and possessed most of the livestock. The situation in the other parishes was less buoyant. As late as 1867, for example, one-half of the Métis grew no grain. The majority of these were concentrated in the new parishes on the Red and Assiniboine where the plains hunters, the boatmen and some of the freighters had settled. This growing disparity between rich and poor was not as evident in English-speaking Red River. [12]

The fragility of the Métis economy was particularly evident in 1868. In 1867 the Métis had harvested some 15,000 bushels of grain; in 1868 the locusts left only 1,200 bushels. The potato crop was equally devastated; the usual 12,000 bushel crop was reduced to 5,000. Those of means managed to buy from the stored surpluses of English Red River, while the hardest hit - the landless, the squatters and the labourers - were only saved from starvation by the charity of the Executive Relief Committee of the Council of Assiniboia. [13]

Neither the merchant farmers nor the landless labourers would rejoice at the Canadian union. That connection would spell an end of the commercial and agricultural hegemony of the St. Boniface merchant farmer elite. P. G. Laurie, a Canadian reporter, viewed their predicament with concern. He sympathized with the Métis fear that the more energetic Canadians would destroy the freighters by introducing railroads and tariffs. [14] Many of the Métis were also afraid that their small, internal grain markets would quickly fall into the hands of the more efficient and "better connected" Canadian farmer. These economic concerns would have predisposed many to accept both Riel's arguments and actions.

Indeed some of the first to become involved in the resistance were affiliated with the merchant group. John Bruce, the first President of the Métis provisional government, was in the employ of two of the more prosperous Red River merchants. Riel for his part drew much of his support from the Lagimodiere side of his family that figured prominently amongst the merchant farmers. This is not to say that the class supported Riel with equal vigour, only that there were reasons for the actions of those who did. Pierre Delorme, one of the first to support Riel, was well aware that the coming of the Canadians would end Métis prosperity. He demanded title to the land the Métis occupied, 200 additional acres for each of their children, and Indian status for their wives, which would allow the Métis to benefit from any Indian land settlement. Most important, he wanted the tract of land lying south of the Assiniboine reserved as a self-governing colony free from all taxation. There the Métis merchant would be protected by a free trade zone. [15] The zone was an impossibility, but the Métis merchant group argued vehemently during the Red River conventions for exemption from customs duties. The best they were able to negotiate was a three-year period of grace before the Canadian duties would be applied.

If the merchant farmers provided vocal support for Riel during the resistance, the Métis boatmen provided the muscle. There is some evidence to indicate that it was these people who manned the Upper Fort and quashed the English counter insurrections. The tradition of mutiny among the boatmen was an old one. In 1859 the Company had tried to redress the "unpopularity" of the Company's service by increasing wages and bettering the treatment of the boatmen. [16] Despite these efforts, the situation became so uncontrollable that the Company decided in the late 1860s to by-pass the brigade whenever conditions made steamboat or cart traffic viable. William Mactavish was prepared to start by replacing the Saskatchewan brigades.

It would in the end enable us to do without the Portage boats, the crews of which have now become a perfect nuisance from their mutinous conduct and unwillingness to carry out any engagement. [17]

The causes of the mutinies were many. While the wages of the boatmen increased from £14 to £20 per trip in the early 1860s, they were still well below those offered for general labour either in Canada or the United States, something of which the men were well aware. Even in Red River itself more money was to be made in haying for the more prosperous farmers than in freighting for the Bay Company. Secondly the conditions on the trip were far from tolerable. The boats were poorly repaired, they were often overloaded and they frequently broke apart. Equally important, by the early 1860s the free traders had ensconced themselves in the Norway House area. They quite enjoyed subverting the Company's brigades. In 1863 at Norway House they liquored up the Oxford House boatmen and persuaded them not only to desert the Company, but to trade the Company's furs. [18]

A more fundamental malaise amongst the Métis boatmen was the breakdown of that hierarchical, almost military society that had been the backbone of the Company. It was a society in which the men and officers knew their place, and in which each recognized the others' rights and responsibilities. The Company's officers were responsible for the welfare and well-being of their servants. Generally the men were responsible for providing the Company's labour. The best of this hierarchical society was seen at the Company's posts in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. [19] Disenchantment was certainly prevalent in the upper ranks as early as the 1830s because of the Company's reluctance to employ the officers' mixed blood children at anything but menial tasks. The change in the Company's management in the 1860s, and the retirement of the old officers in the 1850s probably resulted in the breakdown of the compact between the servants and officers. [20]

During the winter of 1869-70 the boatmen, as was their habit, returned to Red River for the fall fisheries and a comfortable winter. When Riel needed men to seize the Upper Fort on November 19, 1869, in order to consolidate his hold on the settlement, the boatmen were ready to harass the Company they so hated. To them the seizure of the Upper Fort would be the greatest mutiny of all. In 1869 the Upper Fort Garry clerk indignantly recorded approximately one hundred and fifty individual Métis who were in receipt of cash and sundries that Riel had confiscated from the Company. Most were at the Upper Fort from its seizure in the winter of 1869 to the spring of 1870. In comparing these names with the 1868 Executive Relief Committee census, none, it would appear, were men of property or even settlers of modest affluence. They must have been either freighters or labourers. [21] It could also be assumed that the plains winterers were not manning the fort for they were not known to be in the settlement during the resistance of 1869-70. Although they threatened involvement they seem to have confined their activities to the interior.

If the men at the Upper Fort were indeed the boatmen, this would account for the difficulties in the Northern brigades in the summer following the insurrection. Norway House reported that during the winter of the resistance both men and Indians [were kept] in such a state of excitement that the trade was affected considerably. Still the winter and spring passed without trouble excepting two mutinies amongst our people which in both instances resulted in our favour. [22]

In the spring, when the boatmen arrived from Red River, the situation deteriorated even further. Of the twelve boat crews initially engaged in Red River for York Factory only four arrived, the others having refused to embark. Similarly, of the nine boat crews scheduled for Portage la Loche, only three would go beyond Norway House and even then there was no guarantee that they would proceed further than the Grand Rapids. [23] The boatmen were so unmanageable that the Company resolved to abandon the boat brigades for overland transport forever. The "mutiny" at the settlement may have been broken by the Imperial armies, but it continued in the interior with no small degree of success.

While the greatest mutiny of the boat brigades can be said to have taken place in Red River, the uprising of the winterers was confined to the plains. The buffalo were disappearing quickly in the 1860s, the only sightings being the South Saskatchewan and Cypress Hills country. Consequently, the shrunken hunting territories increased the potential for conflict between the Blackfeet and Cree, the Cree and the Métis, and the Métis and the whites. [24] William Mactavish was most fearful that all would eventually fight for the last buffalo in the Cypress Hills. [25] The Métis especially resented the Company's continuing demands for plains supplies. While they realized that the Company was their livelihood, they also knew that it would be their death. The whole of the plains was ripe for a particularly black and vicious storm.

Initially the winterers from the Saskatchewan River District as far south as Minnesota had every intention of joining the fray at Red River. To them it was not so much a struggle to preserve a Metis lifestyle, as a protest against the Company tyranny. In 1869 Mactavish feared that unless the Riel business was settled soon "the Country [would] be overrrun by a lawless horde of sympathizers from Minnesota and Dakotah who under the pretext of aiding would assume the direction of the movement." [26] Mactavish's fears materialized to the extent that the winterers did attempt to seize control of the Saskatchewan and Qu'Appelle districts. In the New Nation of March 4, 1870 rumour had it that in the Shoal and Swan River districts, the freemen had "leaped" to arms, and captured some of Fort Pelly's outposts. While this proved more fiction than fact, the outpost of White Horse Plains was captured and its cattle confiscated and slaughtered. Oak Point and Lake Manitobah posts were also attacked. At Oak Point Mr. Macdonald, the clerk in charge, barely escaped being taken prisoner. He was pursued by a number of Métis but managed to reach Manitobah Post safely. He barricaded himself there and along with eight Scottish servants defended its property against forty Métis. The situation was so threatening that the Chief Trader at Qu'Appelle bundled the furs and slipped them across the border in the dark of the night. [27]

While those at Manitobah Post were convinced that their stand had saved the Swan River District from the ravages of the winterers, the credit is in fact due Pascal Breland, the son-in-law of Cuthbert Grant, one-time warden of the plains. He spent much of the winter of 1869-70 in the Qu'Appelle, Saskatchewan country exhorting the Métis to peace. Breland had, for some still unknown reason, a personal dislike for Louis Riel, and perhaps because of his connection with Grant still had a fondness for the Company. Had he not acted, the Riel protest might have spread like the proverbial prairie fire and consumed the whole of the Saskatchewan country in conflagration. [28]

While knowledge of Red River's social, economic and constitutional history is crucial to understanding the unfolding of events in 1869, so is an understanding of religion. The Métis of Red River were devoutly Catholic, but it must be emphasized that they were not slaves to the institutional church. They might listen to their clergy, but they were quite capable of making individual decisions. The influence of religion amongst the boatmen and plainsmen, in fact, depended more upon the character of the individual priests like Father Ritchot of St. Norbert. There is no real evidence that he determined the course of events during 1869, although he certainly preached resistance from the Sunday pulpit. But his scheme for a Catholic theocracy on the Red, governed by the Catholic clergy, was certainly not seized upon by either the merchant farmers or the boatmen. He was listened to because he struck a responsive chord - Métis culture and religion was in danger from the coming Protestant ascendancy.

The Métis were willing to listen to the warnings of the clergy because of their experiences in the early 1860s. In the first years of that decade the Rev. G.O. Corbett had launched a vicious anti-Catholic campaign in the settlement's newspaper. He not only pointed out, to all who would listen, the threat of a popish plot to gain supremacy in Red River, but the innate inferiority of Catholic religion, Catholic education, Catholic medicine and Catholics in general. So. virulent did sentiments become between the Protestant and Catholic mixed-bloods that James Ross, rather moderate in his anti-Catholicism and at times a restraining influence, refused to publish an obituary of Sister Valade, one of the most venerated of the Saint-Boniface sisters. Ross also became the object of a death threat from Louis Riel père if he continued the anti-Catholic editorials of the Nor'Wester. [29]

Thus when Ritchot and the priests at the forks preached the unfortunate consequences of a Protestant supremacy in 1869, the Métis could only believe. They worked because Protestantism implied bigotry and the probable suppression of their cultural institutions. The merchant farmers feared that, because of their religion, they would be excluded from the commercial elite of the future. Similarly the English mixed-bloods began to believe that every action by a Catholic clergyman was the result of a string pulled by the Pope. So, during the events of 1869, all believed to some degree the warning of their respective clergy. The events of 1869-70 may not have been a sectarian conflict, but the flavouring was strong.

This brief examination of the social, economic, and religious background does not pretend to suggest a new interpretation of the Riel resistance; rather it attempts to suggest perspectives from which new insights can be gleaned with further research. For example, was the resistance really anything more than a grand mutiny of the boat brigades? Was it an expression of the fears of an old Catholic merchant farmer elite of displacement, isolation in a new, unsought Protestant dominated economic order? Was the resistance nothing more than a hysterical reaction by the Métis to the religious railings of the Canadians and their English half-breed supporters? Ultimately this paper suggests that less energy should be spent on analyzing the resistance itself and more on discovering its roots. The resistance has many secret faces. Most of these have yet to be uncovered by the historian.

1. Hudson's Bay Company Archives (hereafter cited as H.B.C.A.) D.5i43, to. 480, John Swanson to George Simpson, May 20, 1857; to. 490, F.G. Johnson to George Simpson, May 23, 1857.

2. The Nor'Wester, May 12, 1863; April 27, 1863.

3. Ibid., June 11, 1863. The words "Provisional Government" were actually used.

4. Canada. Public Archives (herafter cited as P.A.C.) MG29, E2, Thomas Spence Papers, Petition, sec. 3, 1866.

5. Ibid., A. Morrison to Thomas Spence, November 20, 1867; September 17, 1867.

6. Ibid., Thomas Spence, Red River Troubles (manuscript) pp. 11-13.

7. Ibid., Richard Mowat to Thomas Spence, April 22, 1869.

8. Ibid., Colonial Office to Thomas Spence, May 20, 1868.

9. Ibid., A. Morrison to Thomas Spence, April 4, 1868.

10. R. Gosman, "The Riel and Lagimodiere Families in Red River Society," (Manuscript Report Series, No. 171, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, National Historic Sites, 1976) is a good account of the polarization of Métis Society, a polarization that began in 1849 with the free trade crisis.

11. Provincial Archives of Manitoba (hereafter cited as P.A.M.) MG2, B6-2, Executive Relief Committee Census, 1868; MG2, Al-12, Red River Census 1832-1849. These numbers are a product of an SPSS analysis of the Executive Relief Committee and Red River Census Material.

12. The 1868 Executive Relief Committee did not conduct a census for English Red River. That portion of the settlement was not as severely hit by the locust plague.

13. P.A.M., MG2, B6-2, Executive Relief Committee Census, 1868.

14. Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan (hereafter cited as P.A.S.), P.G. Laurie Diary (National Historic Sites Transcript), pp. 1-5. All citations are to this transcript of the original.

15. P.A.S., Laurie Diary, Laurie describes "John Brousse" as a Halfbreed of very mediocre talent and education.

17. H.B.C.A., B.239/c/ 11, fos. 95-97, Governor and Committee to J Clare. June 24, 1859.

18. Ibid., D.9/ I, fo. 56, W. Mactavish to J. Christie, December -. I st6

19. Ibid., B.154/b/9, p. 249-250, J.A. Grahame to W. Mactavish. Septemher 16. 1863.

20. For a good discussion of the hierarchical nature of the fur trade post society see John Foster, "The Country-born in the Red River Settlement," (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Alberta, 1973).

21. Glenbow-Archives, Saskatchewan Correspondence, James to John Sutherland. August 10, 1840.

22. H.B.C.A., B.235/di 228, fos. 54-64, contains the list of names.

23. H.B.C.A., B.154/c/ 10, p. 460, Robert Hamilton to General Council. Julc 12. 1870.

24. Ibid., A.11 fo. 211, J. Mactavish to W.J. Smith, July 12, 1870.

25. J. S. Milly, "The Plains Cree: A Preliminary Trade and Military Chronology 1670-1870." (M.A. Thesis, Carleton University, 1972) is the best account I have come across of the deterioration of the plains from 1850 onward.

26. H.B.C.A., A.11,1 128, fo. 134, W. Mactavish and Committee, March 13, 1870.

27. H.B.C.A., A.l I / 128, fo. 128d, W. Mactavish and Committee, December 11, 1869.

28. For an account of these incidents see Ibid., D. I I 'I, to. 195. W. Mactavish to W.G. Smith, April 16, 1870. See also ibid., A.11 /53, fo. 2, Smith to W. Smith, May 26, 1870.

29. Ibid., A.11 /21, fos. 1-3, R. Campbell to W.G. Smith, April 27, 1870.

30. F. Pannekoek, "The Rev. Griffiths Owen Corbett and the Red River Civil War of 18691870," Canadian Historical Review (June, 1977), pp. 133-149.

Page revised: 22 May 2010