Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1977, Volume 22, Number 3

|

The location and character of the present habitations in Manitoba do not always reflect settlement patterns of the past. That is because subsistence economics often changes. One simple question involved in subsistence economics was: do you live near the source of fuel and water, or do you bring fuel and water to your abode?

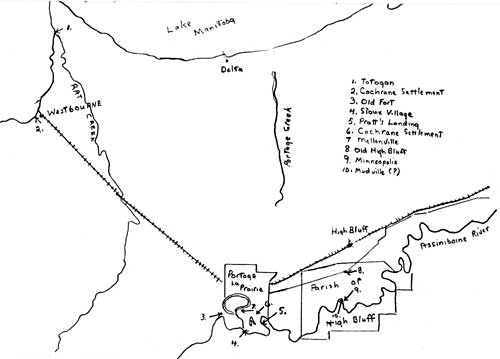

There have been a number of settlements in the vicinity of Portage la Prairie which no longer exist or have changed in character. It is not my intention to discuss every one of these settlements, or to cover those that I do in great detail but to bring to mind the endeavour of the people in these settlements.

Totogan was on the fork of the Whitemud River and Rat Creek (now misnamed Willow Bend Creek). Totogan appears on the map of those surveys completed to 1874. Now, like many others, it is a cultivated field. Spring flooding was a problem for Totogan.

Near Totogan on the Whitemud was "The Landing" for the Hudson Bay lake boats. There was a considerable settlement attached to this enterprise.

For nearly ten years a break-away group of Saulteaux from Yellow Quill's band lived in a village across the river from Totogan and up stream on Rat Creek.

Then there was the Cochrane settlement just west of Westbourne. It is here that "old Bob", the Archdeacon's horse, is buried. Here the cemetery remains.

Old High Bluff stood on the Portage trail between Poplar Point and Portage. It had a hotel, church, and school. As well, there was Dilworth's flour mill. The stones of this steam mill are now at the museum in Portage. There was also a brewery that stood on the edge of the trail on the Moss lot. The C.P.R.'s arrival two miles north killed the settlement. The present High Bluff was built on the track outside the old parish boundary.

Archdeacon Cochrane's Portage settlement, begun in 1851, was at Pratt's Landing on the Assiniboine. The crews who made the lagoon south of Portage dug through the old school foundation. Interestingly, the logs from the school had long ago been moved to Slough Road in Portage and used once more to build a school. Still later the school was turned into a house which still stands today. The landing and Cochrane's settlement are gone except for the cemetery. A warehouse from the landing was brought up to Portage and still stands as a multifamily dwelling near the courthouse.

The "other" settlement in 1851 was the Hudson Bay Fort. It stood near where the water tower now stands on the road to the Diversion Dam. Twenty years later this establishment would be called the "old Fort" by the people. According to Henry Ogletree it was one of three establishments he knew of on his father, The Hon. Frances Ogletree's, land. It was the camp adjacent to the old fort that Frances Ogletree first purchased from the Indians when he arrived from Ontario.

Later when the Hudson Bay moved up to the Saskatchewan Trail on what is now Eighteenth Street, the settlement at the old fort was abandoned. A new settlement grew around the H.B.C. store and warehouse. Here for example was Ross's Blacksmith Shop. Meanwhile, the Ontario people settled on the east side of what is now Portage. The gap, unbroken bush, remained in part until the boom of the Second World War. "East end" and "West end" meant just that in the old days.

In December of 1862 the first of the Dakota Indians crossed the international line as refugees. In 1877 there were 150 lodges in the vicinity of Portage. These Dakota were of the Wahpetons, the Wiyakatidan band. Many later moved to other reserves. Those who remained created Portage la Prairie Sioux Village No. 8a along the Assiniboine south of Portage. Their cemetery can be seen from the bypass.

The problem of destitution among the people of western Canada, has made itself felt from time to time. Two of Portage's solutions have been first to send their destitute out to farmers as labourers, and second, to settle destitute families on parcels of bush land. (The idea being that the destitute would clear the land, build a shack and plant a garden.) Portage had a lot of brush land within its extensive city limits, for in more ambitious days, particularly the boom days, the city had extended its boundary line far beyond its requirements.

The first settlement created in this manner was on Island Park behind the race track. In better years the participants in the venture had no trouble selling the valuable lots.

When the bust hit again in the 1930s and the destitute appeared all over again, Amasa Mellon was on the city council. It appears that Mr. Mellon did not agree with the opinion of the rural councillor who suggested that the country would be better off if the destitute starved, for Mr. Mellon suggested the use of the wood lots. This time the new settlement was along the slough on the south side. It was called Mellonville. This settlement should not be confused with Koko Platz which is in the same general area. All the platz is a subdivision of Portage.

Finally I would like to turn to two distinctly rural settlement patterns that are interesting. The first involves the reusing of the Old Fort stockade. When some of the settlers from Ontario arrived in the Portage district, they lodged their families in the old fort for a year or two until they had established themselves on the plains. For a while, at least, an older settlement was revived. Once they were established the families moved permanently onto the plains.

However, among the Flee Island-High Bluff settlers, there was a habitual migration every fall from the wind swept plains to the shelter of the elm groves of the river flats.

Three winter establishments appear to have been created in this manner, two definitely. One was on the lot of John Moss north of the river, and one on the south side on parish lots one, two, three and four. There is a good chance there was another west of John Moss's lot. The camp on the Moss lot was called Minneapolis. The one across the river may have been called Mudtown. The name Mudtown has been used a number of times in the history of the district. The name comes from the log chinking which was usually white-washed.

Minneapolis had twenty-five or more log shanties at its height. There were shelters for the horses or if they brought stock, stables. Some brought their stock off the plains; others left the stock on the home place to be looked after by a hired man. Often a man who had been hired for thrashing was kept on over winter for this reason. During the winter the men cut and hauled wood to town. Then from time to time they took a load to the home place for the summer needs. Coming back to the river they brought back a load of feed. Later when the railway came through, there was a market for ties.

The major migration of families came to an end about 1891 or 1892, according to Douglas Campbell, former premier of Manitoba, and the only child of Howard Campbell who did not go to the winter settlement. Douglas Campbell's brother, Howard, who is two and a half years older, spent a couple of winters on the river.

While the families no longer made the shift, it did not mean the winter settlements were abandoned at that time. The men continued to travel to the river for wood and some of the younger single men stayed there for extended lengths of time.

In about the winter of 1903-04 two young, newly married women without families, joined their husbands at Minneapolis. They were Mrs. George King (nee Threadkill) and Mrs. Bert Owens (nee Campbell). Each day when George King passed on his way to the bush, he dropped his wife off at Christina Owens' house and the two young women visited. They had an organ in the settlement and in an evening everyone would gather for a sing song. [1]

When wood was moved to the home place the technique was to use a team hauling the wood without a driver, followed by a single horse and cutter. That way no one had to freeze on top of the load or walk to keep warm. Often the slow team was sent out a half hour before the cutter left Minneapolis. As the old timers know, a team heads home to its own barn, most of the time. Mrs. Owens recalled a time the team didn't go home and the men had to back-track, stopping at each farmstead until they found the one the team had decided to visit.

The cut banks that had to be traversed to reach the river flats were not with-out their hazards. One day Bill Ash was riding the whipple-tree or roller in front of a load of wood when he approached a river cutbank at a river crossing. He slipped, went under the load and was killed.

The settlement on the south side of the river on lots 1-4 is on Lee Tulley's land. When Mr. Tulley arrived in 1918, the winter settlement had been abandoned. Mr. Tulley says that only a few pole and root cellar depressions remained.

There is an interesting connection between the old winter settlement on lots 1-4 and the Mellonville days. Mr. Tulley who was also a rural councillor was one of the farmers who housed the destitute in little shacks on his property. Some of the buildings are still in Mr. Tulley's yard. Apparently it was these destitute people, in the days of "work or starve," who brushed off the old winter settlement which became a plowed field.

This article has not mentioned the forts from the French regime, nor the "Pedlars"' establishments on the Assiniboine, Whitemud, and Lake Manitoba. The Dakota camp sites with their rifle pits, twenty or so prehistoric camp sites and the Metis settlements along the river and in the sand hills to the south also have not been discussed. However, I think the complexity of the area settlement pattern has become obvious to the reader.

1. I am grateful to May Thomson of Portage who interviewed Mrs. Owens for me.

Page revised: 14 March 2010