Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1966, Volume 11, Number 3

|

From an unpublished manuscript entitled The God That Speaks in the Public Archives of Manitoba.

Samuel Hearne is known in history for his explorations which culminated, after a third attempt, in his reaching the Arctic coast at the mouth of the Coppermine River. Joining the service of Hudson's Bay Company at the age of twenty he was sent to the stone fort at the mouth of the Churchill River where for several years he traded with the Eskimo up and down the coast of the Bay. He was chosen by the Governor of Fort Prince of Wales to go into the vast unknown territory to the north to find and prospect the place where native copper had been found by the Indians and brought to the Fort.

From a member of the Royal Society engaged in geodetic work at Churchill, Hearne gained an excellent knowledge of astronomy and became proficient in the use of the transit all of which was to prove invaluable in his explorations to the Arctic Ocean. Three journeys were taken in rapid succession in search of the fabled copper ore, from which pure copper could be loaded into ships at trifling expense." On the first and second journeys he was forced to turn back before reaching his destination, but on the third he was successful and was shown the "mine of copper."

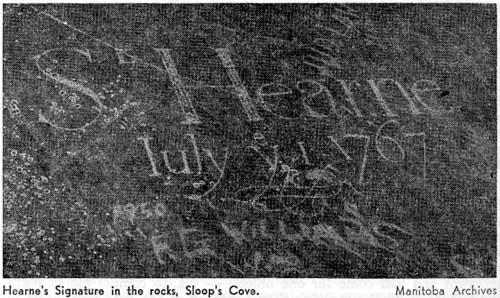

Hearne's signature in the rocks, Sloop's Cove.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

The first exepdition was a complete failure, as the Indians simply took him two hundred miles or so into the wilderness, where, being tired of his company, they robbed him of all he had and left him to find his way back to the Fort as best he could. Fortunately Hearne managed to get meat in the sheltered valley of the Seal River and made his way back to the Fort, which he reached on the 11th of December, 1769.

Undaunted, he started out again in February 1770, with a party of Cree Indians who had been in the service of the Company, using Northern Indians for guides. The latter group claimed to know and have seen the "river of the copper mine". Caribou at this time of the year were plentiful along the wooded shores of the Seal River, but as they could carry very little with them they were soon in want and fell back on fishing in a large lake which would probably be Shethanei Lake. Here they waited for spring and more favourable weather. The pleasant days of waiting, when partridge and fish were abundant came to an abrupt end in mid-April, when, having had little refreshment for three days they lay down to sleep with empty stomachs. On April 24 a large party of Indians came up from the southwest. They were the wives and families of men who had gone to the Fort with fur. Hearne's party were in great distress from hunger and were forced to live on such dried cranberries as remained from the previous summer. This was in spite of an abundance of dried meat in the possession of the Indians.

By August 1770 Hearne and his party reached the flat land west of Dubawat Lake, and here an unfortunate accident occurred which was to put an end to the second attempt to reach the "copper mines." Hearne's quadrant, which had been left standing after an observation, was blown down by the wind and broken beyond repair. He was forced to return, whereupon his followers became restless and allowed a band of strange Indians to steal almost all of his equipment.

Disheartened though by no means defeated, his return to Churchill resulted in his meeting on the way Matonabee who was to be Hearne's friend and guide on the third attempt to reach the copper mines. Matonabee was an Indian of mixed Chipewyan and Cree blood.

With an antiquated quadrant, to replace the damaged one, Hearne and Matonabee left Churchill Fort on December 7, 1771, crossed the Seal and Egg rivers, and turned west to Lake Beralzone. Reaching Neultin Lake they crossed to the Little Fish river which flows to the Bay. Food was scarce one day, plentiful the next. Meat was dried from time to time for use in traversing the Barrens. From February to March they crossed the Kazan River to Wholdiah Lake meeting Indians going to Churchill with fur. Preparations for the long northward journey were made in the Valley of the Thelon River. Meat was dried and suitable wood was collected along with birch bark with which to build canoes to cross the many rivers of the Barrens. These canoes were built in April during the break-up season and in May the party moved north to Partridge Lake.

On arrival at Cat Lake, Matonabee encouraged his Indians to push forward by the promise of war upon the Eskimos. The women and children were to make their way leisurely northward. Taking his striking force - and two of his wives who had no children to encumber them - the party moved swiftly towards the valley of the Copper-mine River. On the way they induced the Copper Indians to join them and sent scouts forward to tell the Indians on the Coppermine of the approaching war party. At the Sandstone Rapids, where the river runs through the first range of hills, scouts reported the presence of five Eskimo tents at the Falls. The warriors daubed themselves with paint and there followed a bloody massacre of which the name Bloody Falls is a reminder to this day. Hearne was disgusted as his journals show. He describes the scene - "finding all the Esquimaux quiet in their tents, they rushed forth from ambush, and fell on the unsuspecting creatures, and they soon began the bloody massacre, while I stood neuter in the rear. In a few seconds the horrible scene commenced; it was shocking beyond description; the poor unhappy victims were surprised in the midst of their sleep, and had neither time nor power to make any resistence ... one alternative only remained, that of jumping into the river; but as none of them attempted it, they all fell a sacrifice to Indian barbarity."

As for the "Copper Mine" which Hearne had sought with so much toil and patience, all that was found of any size was one piece weighing about four pounds. And so the prospect for copper was abandoned and all attempts to get the Chipewyans to trade by coming down to the Fort were futile, which is quite understandable with the everlasting conflict between them and the Crees.

Returning southward toward the regions about Great Slave Lake, Hearne ascended the Slave River and endeavoured to persuade the Crees to resume trading their furs at Churchill for there was evidence already that the Montreal traders had already reached that part of the country. Indeed, upon Hearne's reaching Churchill on June 30, 1772, he was apprised of this fact by Matthew Cocking who had just arrived from York Fort with a report that the Easterners were trading well into the west along the Saskatchewan River.

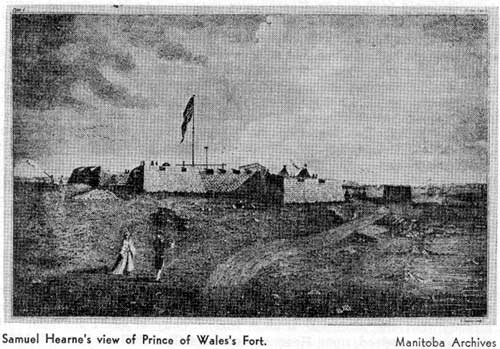

What could be more logical, therefore, than to choose Samuel Hearne to establish a new fort in the interior? Here was a man experienced in the language and ways of the Indian, who had lived with them, established good relations with them and had travelled the north country from Churchill to the Arctic Sea And so, with Matthew Cocking as his assistant, Hearne left York Factory on June 23, 1774 with eleven men and four Indians to establish the first inland fort, Cumberland House. But Hearne was too valuable a man to leave inland when there was a new fort to be built at Fort Prince of Wales (Churchill). This was indeed a fortress built to withstand any assault by the French from the sea. Walls of solid masonry, thirty to forty feet thick and three hundred feet long did not, however, prevent La Perouse in 1782 from entering the mouth of the river and landing some three or four hundred Frenchmen from three ships. Hearne was in charge of the Fort, and it has been suggested that his weak and passive nature was responsible for its ready surrender. It is true that the fort was elaborately armed yet it was quite beyond the ability of a handful of men to defend against trained soldiers, especially as the defenders were traders and not fighting men.

Hearne and his men were taken prisoner and placed aboard the French ships while La Perouse plundered the fort, destroying as well as he could the massive masonry which had taken thirty years to build. Next to be attacked and destroyed was York Fort, after which the French left the Bay. However, that magnanimity which so often showed itself between victor and vanquished in those days resulted in Hearne and his men being sent to England in one of the Company ships and, under the promise that he would complete a book, he was allowed to keep all his valuable journals, papers and notes.

Samuel Hearne's view of Prince of Wales' Fort.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

After another short period at Churchill Fort in 1783 when the stone fort was abandoned and Hearne had established a new frame fort five miles upstream, he returned to England in 1787. His last years were spent preparing his book for the press, but he died in 1792 with the work unfinished. [1]

1. His account, "A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort to the Northern Ocean" appeared in 1795.

Page revised: 18 July 2009