by Sister Mary Murphy *

MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1944-45 season, read 11 December 1944

|

The Grey Nuns' Congregation was founded at Montreal in 1738 by Mother d'Youville. The Saint Boniface Mission at Red River was established in 1818 by Bishop Norbert Provencher. The Grey Nuns arrived in 1844, in response to the Bishop's invitation, to teach children and care for the sick. In 1944, a cairn was erected to their honor in La Verendrye Park, St. Boniface. Many things have changed in the last hundred years, especially in the ways of traveling. In this paper a sketch will be given of a few of the early expeditions of the Grey Nuns to the West.

On the morning of April 24, 1844, several carriages drove away from the old Motherhouse at Pointe-a-Callieres, Montreal. They were on their way to Lachine with the four first Missionary Grey Nuns, Sisters Valade, Lagrave, Coutlee (St. Joseph) and Lafrance. They were accompanied by Mother General McMullen and several Sisters and relatives. The Sisters called on Sir George Simpson, the Resident Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, into whose territory they were going, then crossed to the isle of Dorval where two canoes were in readiness for the trip to the Red River. Murdoch McPherson, an officer of the Hudson's Bay Company, travelled with his family in one canoe, the other was for the Sisters. A crew of sixteen voyageurs, under the command of Captain Dore, awaited the signal to embark. The departure was postponed, however, because of a downpour of rain with thunder and lightning.

The tents were pitched for the night. Each tent measured about fifteen feet by ten. A fire was built under the tripod and supper was prepared. An oilcloth was spread on the ground and all sat around as best they could and partook of the travelers' meal. Their food supply consisted chiefly of salt pork, beef, tongue, sausages, fish, butter, sugar, dry biscuits and good black tea.

The escort party then returned to Montreal. It grieved Mother McMullen to be unable to go with the Sisters to Red River. Maurille Coutlee, a brother of one of the Missionary Sisters, was inconsolable. It added to his sorrow when the steamer failed to come, on which he had wanted the Sisters to travel as far as Carillon.

When the partings were over, our heroines dried their tears, said evening prayers and retired to their tent. Each had a pillow, a blanket, and a large piece of oilcloth to wrap under and over the blanket. Thus they slept on the ground each night until they reached their far-away destination.

Long before daybreak of April 25, the Sisters were aroused, not by the familiar convent bell, but by Captain Dore yelling "Leve! Leve!" Soon they stepped into the frail birch bark canoe, and the voyageurs sang a merry boat song, as they glided away from Dorval.

The canoe in which the Sisters traveled measured about thirty-six feet in length and five feet in width, and carried four thousand pounds of cargo, apart from ropes, sails, guns, harness, and camping equipment.

They followed the route of the old fur traders. La Verendrye, who was Mother d'Youville's uncle, had travelled it over a hundred years previously - Ottawa (Outouais) River, Mattawa River, Vase River, Lake Nipissing, French River, Lake Huron, St. Mary's River, Lake Superior, Kaministiquia River, Rainy Lake, Rainy River, Lake of the Woods, Winnipeg River, Lake Winnipeg, and Red River.

The day after leaving Dorval they stopped at Carillon, where the aforementioned Maurille Coutlee resided. It had been promised that the Sisters would spend a few hours at his home. Within half an hour, Captain Dore rushed in and explained that some of the canoemen were planning to skip away, if given time to do so. They re-embarked at once, but not without Maurille Coutlee who accompanied his sister to the Long Sault canal.

A word about the canoemen. In those days there were thousands of Indians and Metis all over North America, who were expert travelers and guides, and were generally known as voyageurs. They were very strong, alert men, with kindly hearts and a vocabulary as rugged as themselves. When Captain Dore selected the men for the Sisters' canoe, he gave them a lecture about their language. Let it be said to their credit they tried to be very careful, but the habit was strong. Some of the boat songs were also off colour. This situation was offset by the Sisters who prayed aloud at intervals, read from pious books and sang hymns. Sister Lagrave composed other rhymes for the songs in question. This proved to be good psychology as the voyageurs gladly accepted the new versions. Sir George Simpson was greatly amused when the men told him about it later.

On April 27, they camped near the village of Hull. Father Telmot O.M.I. came across the river to greet them. He was from a little place called Bytown which was later to become Ottawa, the capital of Canada. They reached Aylmer in time for High Mass on Sunday, much to the surprise of Father Desautels and his flock. After Mass the Sisters returned to the canoes escorted by the congregation.

Although the voyage became harder as they left civilization behind, it was not without its pleasant and consoling days. The Sisters enjoyed the sunrises, the fine spring weather and the rich wild scenery all around. On calm days they sewed, knitted and did fancy work as they paddled along. They also wrote letters. They sometimes camped near Indian villages and the Sisters often entertained the people by singing for them.

On Lake Nipissing they were overtaken by Sir George Simpson and Bishop Provencher, who had left Montreal four days after the Sisters. Father Joseph Bourassa and Father Louis Lafleche followed in another canoe. All stopped for a friendly visit, then the Governor's speedy canoes paddled off and were soon out of sight.

The greatest hardship of the trip was the crossing of the seventy-two portages between Lachine and Red River. As each canoe was emptied two men tossed it over their heads upside down and carried it across the portage. The others put on the portage harness. The captain loaded each man with two hundred pounds of cargo or more, which was fastened on their backs with a strap that passed over the forehead. Many years after, the Sisters often said the hardest part of the trip was the sight of these men bending under their burdens as they tramped over fields or hills and through the bushes. The Sisters carried their own belongings, which were very light. On Lake Huron, Sister Lagrave sprained an ankle and had to be carried the remainder of the way. She had a fever and chills after the accident and the Sisters wondered if her grave would not be marked by a cross on a lonely shore, like so many they had seen on the way.

Lake Huron and Lake Superior being great inland seas, the canoes were too light to be launched into the waves. They had to keep close by the shore all the way, and it took two weeks to cross these two lakes. Father Bourassa and Father Lafleche, who had remained at Sault Ste. Marie to visit the Indians, continued the route with the, Sisters to St. Boniface. They made a stretcher for the invalid Sister and helped to carry her across the portages.

Notwithstanding the acuteness of the voyageurs in sensing the approach of storms, they were taken completely by surprise on Lake Superior. A wind turned the lake into a fury in a few minutes, and they were too far out to reach land. All they could do was hang on. The little canoes rose up and down like feathers on the waves. With jaws set and muscles tense the men balanced the canoes with marvelous dexterity. There was no panic although faces were white and eyes were wide with fear. The Sisters thought each wave would dash them into eternity. The silence was intense except for the terrible noise of the water. Suddenly the captain's voice was heard. "Pray," he shouted "please pray!" Father Lafleche recited the Litany of the Blessed Virgin. To each invocation all fervently responded Ora Pro Nobis. After two hours the storm subsided and they reached the shore. The voyageurs fastened the canoes and sank to the ground, exhausted. The others prepared a hot supper which revived the tired men. The next day they reached Fort William. It was the 29th of May.

At this point the cargo was transferred from the lake canoes to the river canoes, which were much smaller. The trip into the interior of the country lay ahead. It was here that the Sisters were told it would be impossible to take their helpless companion further. After much discussion the decision was reversed, and the four Grey Nuns continued on their way.

The next part of the trip was nearly all up hill. There were numerous steep portages. The rivers were narrow. The mosquitoes were terrible. At one place Sister Lagrave had to be hoisted on the stretcher over a waterfall fifty feet high. (Probably at Kakabeka Falls.) Eventually they reached the height of land, somewhat east of Lake la Croix. It was an old landmark, as up to this point the rivers and lakes flow eastward, and beyond it the waters flow in a more or less north westerly direction.

Their next worry was their food supply. It was almost exhausted on June 7. Two days later, however, they received a supply of pemmican at Fort Frances on Rainy Lake. The voyageurs ate it with relish, but it nauseated the Sisters, to whom it looked like shoe leather. Nevertheless, they came to like this food which was to be the Grey Nuns' staff of life during their first thirty years at Red River.

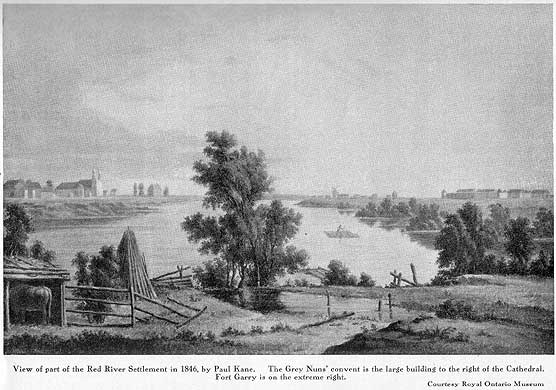

They crossed Lake of the Woods and navigated the difficult Winnipeg River. One fine day the voyageurs cheered as they slung the harness into the bottom of the canoe - the last portage had been crossed. (Probably at Pine Falls.) They reached Lake Winnipeg and turned south into Red River. On the afternoon of June 20, they arrived at Fort de Pierre, which is now called Lower Fort Garry. They were invited to spend the night at the fort. A messenger was to go to notify Bishop Provencher of the Sisters' arrival. Another plan was followed, however, and the travelers paddled on. The sun went down and the stars began to shine as the canoes came nearer and nearer to St. Boniface. At one o'clock in the morning of June 21, 1844, the Grey Nuns landed in front of the cathedral. They had covered about two thousand miles, in fifty-nine days.

Their baggage came by a different route. It was shipped from Montreal to England, then back across the Atlantic in a Hudson's Bay ship, through Hudson Strait, into Hudson Bay and up the river to Norway House, thence across Lake Winnipeg to Red River. It arrived three months after the Sisters. This roundabout way was cheaper and much less trouble than the direct route by the Great Lakes. It shows what handicaps the North West Company labored under in their competition with the Hudson's Bay Company, who used the sea route by Hudson Bay.

It may be of interest to know that among other things the Sisters of 1844 brought a grandfather's clock. It remains to this day in the Community room in the old convent at St. Boniface. It is still ticking off time and striking the hours, just as it did a hundred years ago.

One other group came by canoe. They were Sister Withman and Sister Cusson who arrived with the first Oblate Fathers at St. Boniface, on August 25, 1845. The names of the Oblates were Father Casimer Aubert and Brother Alexandre Tache who later became the second Bishop of St. Boniface.

The same year the Grey Nuns at Red River received their first novice. Her name was Margaret Connolly. Both Bishop Tache and Sister Connolly were distant relatives of the famous explorer, La Verendrye.

After this date the old canoe route was abandoned by the Missionaries, as newer methods of travel had developed.

Brief notes have been made on seven or eight subsequent trips. They will lift as it were the corner of a veil, and merely give us a glimpse of Grey Nuns going hither and thither. By following in their steps, however, one can trace fairly well the advances of the steamship, the stage coach and the railways, as they reached out to the Mississippi Valley, and our own Canadian West.

The route travelled by Sisters Gosselin and Ouimet in 1846 was as follows: they left Lachine by steamer on July 10, and changed steamers at Kingston, Toronto, Niagara, and Buffalo. At Buffalo they embarked on a much larger vessel and after six days they arrived in Chicago. They traveled two days and two nights by stage coach to St. Joseph on the Mississippi, and continued by stage coach to Galena, a lead mining town, on the same river. They waited nine days for the steamer from St. Louis on which they traveled as far as Stillwater. From there they drove seven hours by wagon to St. Paul, Minnesota. They waited six days in the future capital of Minnesota for a caravan of thirty Red River carts and trekked across the prairie to St. Boniface. It took fifty-seven days from Montreal to St. Boniface. The Sisters said it was a good trip.

Mother Valade and Sister Ouimet returned to Montreal in 1849. They crossed Minnesota and arrived in Montreal on October 15. It is recorded as a good trip and was completed in forty-seven days.

Mother Valade was the foundress of the St. Boniface Convent in 1844. When she returned to Montreal five years later, she solicited help for the young foundation. She spent a busy winter in the East and recruited three more Grey Nuns, three lay women, and two men.

These nine brave souls set out from Montreal on June 19, 1850. They crossed the Lachine Canal by steamer and proceeded by train and stage coach to Buffalo. They arrived on June 22, and were ten minutes late for the steamer that set out to cross Lake Erie that day.

The disappointed travelers were directed to the convent of the Sisters of St. Joseph. Mother Valade and a companion went to the door and asked for shelter. The Superior said: "Certainly, you are both welcome." Then Mother Valade said timidly, "There are seven others outside." The Superior threw her arms up saying: "Oh, you're too many!" But she took the words back quickly and they were all kindly received.

During the night a storm arose and all shuddered as they listened to the roar of the lake. The Sisters thanked God they were safe in the little convent at Buffalo. The next day was Sunday and Father Bernard O'Reilly said Mass at the convent. In a short but touching sermon he told them the steamer St. Lawrence had been lost during the night, and about three hundred had perished. He exhorted them to pray for the departed, and also to bless God for watching so tenderly over the Grey Nuns. It is recorded that "Everybody wept". On Monday the Sisters boarded another vessel and passed by the scene of the recent tragedy. They saw the stark prow, still above the water, and the name St. Lawrence clearly visible.

The three new Missionary Grey Nuns who made this trip with Mother Valade were Sister Fisette who spent sixty-four years in St. Boniface, Sister Laurent who died in 1926, after spending seventy-six years in St. Boniface, and Sister L'Esperance who passed fifty-two years in St. Boniface and was one of the writers of the manuscripts we treasure today.

It is recorded they traveled four days by stage coach to Galena, embarked on a steamer on the Mississippi on June 30, and reached St. Paul on July 3. They had to wait one month for the caravan. It was delayed because of bad roads.

The party began pitching tents and unpacked the cook stove. Just then Father Augustine Ravoux appeared on the scene. He said he had two houses, one at St. Paul and the other at St. Peter's (now Mendota). He invited the Sisters to take his house at St. Paul and the kind offer was accepted.

The Father's hut was about twenty feet square. There were two rooms and also a garret reached by ladder. For furniture there were two chairs, a table, a poor bed, a cupboard and a few boxes.

As stated before there were two men in the group. Mother Valade had them repair the house and make a lean-to for the stove. For the rest of the month the men were hired by the farmers around St. Paul. Mother Valade bought provisions for her household, but the good people of the place also came to visit the Sisters and they did not come empty-handed. They brought milk, butter, eggs, bread and cakes.

The Sisters did not remain idle. Father Ravoux permitted them to teach catechism to the children of the Mission. Sister L'Esperance taught the Frenchspeaking children, and Miss Ford, a member of the group, taught the English speaking class. About forty children attended. The Sisters also washed and mended the church linen and put the priest's wardrobe into as good order as possible.

On August 3, the Sisters left St. Paul. They formed a part of Norman W. Kittson's imposing caravan of eighty Red River carts, that clattered away in single file across the prairie. The first night they camped at St. Anthony's Falls, now in Minneapolis. The Sisters were given hospitality by Mr. and Mrs. Pierre Bottineau, formerly of St. Boniface, who confided their ten year old daughter to the Sisters for her education. Little Marie left with the caravan the following morning.

It was a difficult trip through innumerable swamps, muskegs and rivers. There was constant danger of an attack from the Sioux Indians, who at that time violently objected to the crossing of Minnesota by white people. For all these reasons, many detours were made. As the march stretched out into six hundred miles the food diminished. All were put on daily rations of a little rice boiled in water. The hungry people ate berries they picked by the way. It was a dilapidated caravan that straggled into Pembina on September 8. The animals were lame and tired, many of them had died on the prairie. Mr. Kittson tried to procure a barge for the Sisters to finish the trip down Red River. After waiting in vain for eight days they set out again with twelve Red River carts and --reached St. Boniface four days later. It was ninety-two days since the Sisters had left Montreal.

The dates for the departure of the caravans were fixed a long time ahead. But it was impossible ever to forecast the number of days it would take to make a trip. Traveling was very uncertain, even for expert caravan men like Mr. Kittson.

Of those who set out from Montreal in 1853, Sister Pepin did not remain long in St. Boniface, but Sister Curran remained thirty-four years and was the other chief writer of the early manuscripts. Sister Mary Xavier (Margaret Dunn) was the Grey Nun with one arm, who was known far and wide in the old days. She lived forty-two years in St. Boniface.

This group left Montreal on July 6, passed by way of Buffalo and set out from St. Paul on July 30. Mr. Goulet was in charge of the caravan and Father Georges Belcourt also made the trip.

On July 31, they attended Mass at St. Anthony's Falls, and again at Crow Wing probably on August 14. At the latter place the High Mass was sung to the accompaniment of a fiddle.

In her notes Sister Curran writes: "The first day on the prairie we were admiring God's beautiful country around us, but" she adds "our pious reflections came to a sudden end when the cart tipped over and we all fell in the long grass. We soon learned Red River carts often tip over. Another day an ox suddenly turned down the river bank for a drink and the cart fell into the river. Several webs of calico were soaked in the water. That day the Grey Nuns spread yards and yards of calico in the sun to dry, on the green fields of Minnesota."

The Sisters dreaded the snakes. They seemed to be everywhere. "One evening" writes the same Sister, "we were sitting under a tree. Suddenly I saw the edge of my dress move. I jumped up and there was a big snake." Then she adds, "I never knew before I could scream so loud." The note continues: "From day to day we met bands of Indians who passed by peacefully, but one day a fierce Indian tried to stop us single-handed. He used very threatening language, and even the men were afraid of him. Finally, Mr. Goulet took out the tomahawk and you should have seen the Indian go.' The same writer continues: "One day the men shot a bear, the meat was excellent." This caravan reached St. Boniface on September 12.

The caravans from Minnesota came in by way of St. Norbert on the west side of Red River. They halted on the south west point where the Red River and the Assiniboine meet, opposite the present St. Boniface Hospital. In the old days the Sisters always watched for the caravans coming in. When they saw Grey Nuns they went over by canoe and brought them home to St. Boniface.

Among the Sisters who came in 1855 were Sister St. Theresa (Margaret McDonnell) foundress of the present St. Boniface Hospital. She died in St. Boniface in 1917. Also Sister Dussault who lived sixty-seven years in St. Boniface, and Sister Ste. Marie (St. Julien) who remained only four years at Red River, but never forgot it. Forty years later she said in a conversation that one could never imagine the beauty of the western prairies as she saw them, covered with wild roses, in 1855.

There were no return trips and no new missionaries until Mother Valade went to Montreal again in 1858. It was on this occasion that Bishop Tache gave her charge of three boys he was sending to College in Quebec. They were Louis Schmidt, Daniel McDougall, and Louis Riel. The last mentioned boy was then fourteen years of age, and later took a hand in making history.

Mother Valade returned with several Sisters who were destined to open missions in the north, one at St. Anne (near Edmonton) in 1859, and another at Ile a la Crosse in 1860.

Since the foundation in 1844, Mother McMullen had wished to visit Red River. In 1859 she came. In a letter of seven thousand words she has left us an account of the details. Needless to say the following is only an outline.

Word had been received at the Motherhouse on September 23, that Mother Valade's health was failing. It was decided that Mother McMullen should go at once with Sister Clapin to Red River. Sisters Ethier and Pepin had set out a week previously and it was decided to try to overtake them at St. Paul. Mother McMullen and her companion left Montreal by train the same evening, and next day they reached Sarnia and crossed by steamer to Detroit and went from there to Chicago by train. There was a slight delay when the train ran off the track, but they soon continued by train to Prairie du Chien, on the Mississippi.

While waiting for the steamer a man offered to take them to the priest's house. The Sisters declined at first, but he insisted so much they decided to go. To their amazement he took them into a fine hotel of which he was the proprietor. His good wife showered the Sisters with kindness and the story winds up by saying "He was an Irishman."

When they reached St. Paul the caravan had already gone. They proceeded by stage coach to St. Cloud where they overtook the other Sisters. After spending a day with the German Benedictine Nuns near St. Cloud, the four Grey Nuns set out across the prairie on October 5. It was a small caravan of three or four men and a few girls, with three or four young Métis guides in charge. The oldest was 22.

In the old days there were three roads across the prairie from St. Cloud to Red River. There was the Woods Road (Chemin des bois) that passed through Crow Wing. On it people were least likely to be attacked by the ferocious Sioux. There was the Prairie Road (Chemin de Large) that lay to the west and passed directly through Sioux territory. The third road ran between and was called the Middle Road (Chemin du Milieu).

Soon the passengers suspected they were on the dangerous Prairie road. When questioned, the guides gave vague answers. What was the consternation of the Sisters when they discovered they were traveling with bootleggers! Crow Wing had been avoided purposely because a police officer was stationed there.

It is a long story about the arguments between passengers and guides. They attempted to change roads and were completely lost for several days. The weather was cold, food was scarce, the Sisters had to drive the carts themselves. They were surrounded by prairie fires, stuck in the mud, and lived in terror of the Sioux Indians. Moreover the caravan was poorly armed. They had but four guns.

Reference is made to the youngest guide. He was only seventeen, but he did all in his power to befriend the Sisters and to help them in their distress. His name was Colin McDougall.

Sometimes the nights were more trying than the days. The Sisters and the girls had their own tent, but often they could not rest. In another tent nearby the guides often held pow-wows. They would sing and dance, play the fiddle and shoot off guns until early morning, then sleep until noon. The Sisters feared the Sioux would hear the noise, and moreover the skies were often red with the glow of distant fires. At such times the Sisters took turns keeping guard all night, at the tent door.

Note is made of certain places they passed on the way. They crossed a river by ferry near Richmond, camped one night near Sioux Lake, had difficulty in crossing Ottertail River, and at one time tried to send a message to the American Fort (undoubtedly, Fort Abercrombie.) It is also stated it took several hours to ford Red Lake River.

Although the guides were young and reckless, Mother McMullen gives them credit for their patience and their unalterable good humour. She realized the trip was hard for them too. Many times a day they had to go in the mud, not only to the waist but even to the shoulders and pull out the oxen and carts, and then continue the march in their wet clothing.

At times these boys tried to reassure the Sisters that all would be well. One day a guide gallantly exclaimed: "Sisters, you have nothing to fear! We will defend you with our lives! If the Sioux come they will have to kill us first and you after!"

One day the guides undoubtedly did save the entire caravan, including the Sisters' lives. There was a prairie fire at a great distance and the caravan was moving slowly along. Suddenly the guides noticed the wind had changed in heir direction. In the flick of an eye they set fire to the field around them, quickly pushed the caravan on to the burnt patch and turned the carts upside down. They were just in time. In a few minutes an ocean of fire came rolling owards them. It went all around but did not touch them. The oxen were bellowing, the dogs were howling, and the Sisters and girls were rolled in blankets under the Red River carts.

These weird experiences bring to mind the old adage of the cowboys, that "A good woman is safe anywhere." It held true for the Sisters, for in all their hard travels no one ever tried to harm them. On the contrary they were always given the best, such as it was.

After many trials and tribulations they came to Pembina at last, and spent the night in the school house. The next day Bishop Tache's carriage came for them and they arrived at St. Boniface on November 3.

Bishop Tache was annoyed with the older guides for carrying liquor on the journey. He praised the youngest one for his goodness to the Sisters and as a reward he took him to the pasture and bade him choose the animal he wanted. The lad proudly took possession of a big ox.

Good trips and bad trips through Minnesota ended in 1860 when steamship service was inaugurated on Red River. Then it was possible to reach Montreal in twelve days. In 1878, the Soo Line Railway to St. Paul reduced the trip to five days. Now we go to Montreal over our Canadian railways in a day and a half. If in a hurry, we can go by plane in eight hours.

Such is the evolution of travel as found interwoven with the history of the Grey Nuns at Saint Boniface.

* The material for this paper, read before the Historical Society of Manitoba was taken from the manuscripts of the Grey Nuns at St. Boniface.

Page revised: 22 May 2010