MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1961-62 season

|

In attempting to recreate a picture of the Souris-Assiniboine fur trade area as it must have been in its hey day, we must examine two kinds of evidence—the physical evidence of the sites themselves, and the written evidence which survives in the letters and journals of men who were part of the life of the fur trade in the years between 1793 and 1821. It is difficult to say which is the more exciting task.

If we begin with the abandonment of the area as a fur trade centre we find that during the sixty years that followed, while settlement and trade came to centre at the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine, and while the range of the great buffalo herds retreated farther and farther west, this once busy trading nucleus sank into oblivion. At last, even the physical evidence of the sites themselves dwindled and decayed until they were no longer easily discernible in the natural landscape. The Indians continued to make sugar in the bush, and to camp at their long-established, seasonal locations along the river. Indians and Métis buffalo hunters continued to cross the river on the old trail to Turtle Mountain and the Missouri as they had from time immemorial; but the old way of life was passing and a new one was coming into being.

By the late 1870s, the trail from Portage to the Souris-mouth carried the carts of the first settlers on the Souris plains, and by 1880, a Dominion Government Land Office was established at the junction of the Souris and Assiniboine. Although the old trading posts are often called the Souris-mouth group, this land office (1879-1881), and the Two Rivers post office and hardware store of the 1880s were the only businesses ever to be carried on at the mouth of the Souris. At the same time, the thriving little town of Millford was established three miles up the Souris at the spot where Oak Creek flows into the valley from the South. The tide of settlers had arrived-all unaware that this had once been an important centre for the gathering of “plains provisions” in an era of fur trade rivalry that had long since passed away.

One might think with regret of historic sites that fell victim to the homesteaders’ need for cultivated acres. No doubt these pioneer farmers supposed that the strange hummocks and hollows in their fields were some work of man, but since detailed local history of this sort is still largely unwritten, it is unreasonable and unjust to condemn the individual farmer of eighty-five years ago for his ignorance of it.

The first person to take an interest in these locations was Rev. George Bryce, who visited the district in 1886 and inspected some sites. A few years later, in the summer of 1890, the late Mr. J. B. Tyrrell was working as a geologist on the Geological Survey of Canada, and in descending the Assiniboine from Fort Pelly to Portage la Prairie, he stopped to examine three sites on Section 19-8-16 West 1st. On his passage downstream he had missed the two most recently abandoned sites which had been the scene of the prelude to Seven Oaks in 1816.

The sites that he examined were those of the earlier downstream group active at the turn of the nineteenth century. The detailed descriptions which he gives of his findings are invaluable, for even then, the passing of some eighty years had done much to obliterate the fragile record to be read in their remains. The complete text of Tyrrell’s notes may be studied in the appendix to Transaction No. 5, published by the Historical Society in 1930, and consisting of a paper by Dr. David A. Stewart entitled “Early Assiniboine Trading Posts of the Souris-mouth Group.”

My own interest in this particular group of trading posts arose from a close study of this publication, as well as from a period of residence on the south bank of the Assiniboine, fewer than three hundred yards from two of the sites in the group which Tyrrell examined. As a result of this association I was always alert for any reference to the Souris-mouth forts that I might find in the course of other research.

Some years ago, on reading one of Peter Fidler’s letters written in the spring of 1816, I was puzzled to find a clear implication that “the French House” was in sight of Brandon House where he was stationed, and a reference to “our old house” was also disturbing, for these references could not be reconciled with Dr. Stewart’s findings.

Prompted by the re-thinking of evidence which resulted from this apparent discrepancy between contemporary record and Dr. Stewart’s assumptions, my husband and I made a trip out to examine the upstream sites more closely. Thus, one cold, bright morning of early spring, before there was growth to prevent a clear view of the earth’s surface, and with the advantage of a brisk wind to lift the light soil and expose buried artifacts, we began to take a closer look at a south side location on Morgan’s farm opposite what we had always believed to be the site of Brandon House. Here, on the first terrace back from the river, where cultivation extends right to the line of trees at the rim of the bank, we found unmistakable evidence of a large post, and one that must have been occupied for a long time judging by the density and extent of the food refuse in the form of bones and clam shells that could still be found in land so long cultivated. It seemed that this site had not been properly identified, for according to Dr. Stewart’s research, the only time that this land had been occupied was in the period 1817 to 1819, after Brandon House (believed to have been on the north side) had been ransacked by North West Company adherents on their way to Red River and the fateful collision at Seven Oaks. It seemed certain that this large west-bank site must have been more than a temporary Hudson’s Bay post in 1817-19, for the traces of long occupancy were too many and varied and spread over too wide an area to be dismissed lightly. Among the items found in a brief examination were pounds of bones split for the marrow, quantities of broken clam shells, a large amount of sheet metal clippings, pieces of broken china, a large metal weight probably from a plumb line, a musket ball, bits of coloured glass and a metal button with the words “H.B.Co.” inscribed on it.

There were many possibilities to ponder, and so I began to look for new written evidence, and to re-examine the old. In doing this, one must go back in time to the days when the first posts were established in the area, and follow year by year all the surviving written evidence that concerns them or their successors.

Consider first some background information relative to the decade in which the Souris-Assiniboine forts began their trading careers. One should remember that the traders moved into competition in this area comparatively early in the era of active North West Company Hudson’s Bay Company competition; for at the time of their establishment, in the early 1790s, it was fewer than twenty years since the Hudson’s Bay Company had made their first move inland. In this founding period, the Hudson’s Bay Company expansionists were operating on what amounted to a regional basis. Their traders from York Factory continued to press up the Saskatchewan and were somewhat at odds with the people from Fort Prince of Wales as to the best approach to the Athabaska territory. In the buffalo country to the south it was the Hudson’s Bay traders from Albany who pressed for entry into the plains. As early as 1789, the Canadian, Donald McKay, was offering his services to the men of the Southern Department, promising to set up posts within five years in the Southern area.

The Nor’westers were well ahead of their rivals in the buffalo country. Cuthbert Grant Sr. and other North West Company bourgeois had been trading there for upwards of ten years; and by the early 1790s, were well established on the Qu’Appelle, the Upper Assiniboine, and in the Swan River district.

In assessing the importance of the trading posts in this southern area, one must not forget that their real significance lay in their proximity to the great buffalo herds of the Souris Plains. Here quantities of “plains provisions” (that highly concentrated foodstuff, pemmican) could be collected. As the line of posts to be serviced and supplied in the short summer season reached farther and farther inland and away from home base, supply lines lengthened, and pemmican increased in importance. The area was fairly productive of furs, but the pemmican which it could produce, collect and store gave it great significance in the fur trade scheme of things; for while this commodity was important enough to the Hudson’s Bay Company, to the North West Company with their long supply lines it was absolutely essential.

Our discussion began with the abandonment of these sites, and their gradual decay through some one hundred and forty-odd years to their present status as curiosities, of interest from an archaeological point of view. Let us now go back further still, to a time just one hundred and seventy years ago when these trading posts had their beginnings, and follow them through their years of activity and importance, noting that the Souris-Assiniboine area’s existence as a trading centre lasted for almost thirty years.

John Macdonell’s Journal, written as he travelled inland with bourgeois Cuthbert Grant Sr. records the details of the push west in the fall of 1793:

“Thursday 5th September - (1793) - Overtook D. McKay and his Hudson’s Bay Party in the Rapid of sault a la Biche St. Andrew’s Rapids (they having passed us while trading with the savages at the entry of the Red River) ...

September 11th, Wednesday - The Strip of Wood that lines the River has now got so large that we remain in the canoes as it might be troublesome to find them when required. Passed the site of an Ancient Fort de La Refine. The spot on which it stood can scarcely be known from the place being grown up with wood. Supped upon a bear killed by the hunters ...

Saturday 21st ... I set out on foot for Fort (Pine Fort) distant ten leagues and arrived at it, two hours before sunset. Starvation worse at the Fort than along the road. The people who were out in various directions looking for Indians with provisions returned on the 26th with nine lodges of Assinibouans well loaded the pieces of meat ...

Saturday 28th - Sent off the canoes and goods for the upper posts. It begins to freeze hard at night. Indeed it is remarked that the frost invariably begins here about the 25th of September ...

Monday, September 30th - Left the Pine Fort on foot having a few horses to carry our provisions and bedding, for we are not to sleep with the canoes any more ...

Tuesday, 1st October - Mr. C. Grant placed Auge in opposition to Mr. Ranald Cameron, whom Mr. Peter Grant settled at a new place two miles above the mouth of the River La Sourie; a small river from the S.W. that empties itself into the Assinibouan River.” [1]

As Macdonell and Grant proceeded west to the Qu’Appelle, Donald McKay of the Hudson’s Bay Company was pressing hard towards a favourable location for his fort. The Hudson’s Bay Company records show that the foundations of the new post were laid on 16 October 1793, and at five the same afternoon it was “baptized Brandon House.”

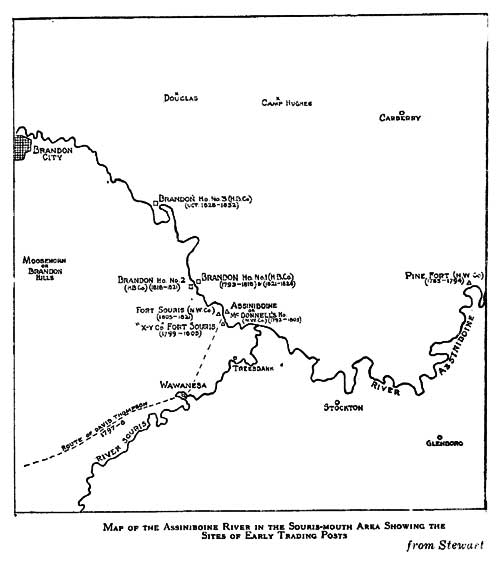

Map of the Assiniboine River in the Souris-mouth area showing the sites of early trading posts.

Source: Stewart.

The exact location of the Brandon House founded this day is in some doubt, but we know that it was on the northeast bank of the Assiniboine. Dr. Stewart assumed that the original site was still in use in 1816, at the time of Seven Oaks, but the Brandon House of Peter Fidler’s day (1816) was several miles upstream from the original North West post for which we have a precise distance of two miles from the Souris mouth in John Macdonell’s Journal quoted above, as well as a latitude reading from David Thompson’s Journal of 1797. It is plain that so great a distance, as well as difficulties of terrain along the north bank, simply do not jibe with three separate items of written evidence. In May, 1794, the spring following the establishment of these posts, John Macdonell was returning east with Cuthbert Grant, Sr., the bourgeois in charge of the spring brigade. Macdonell’s journal relates:

“May 6, 1794, arrived at Auge’s River la Souris Fort; sun an hour high. Auge has sad complaints against his H.B. opponent, Mr. Donald, alias “Mad” McKay ...

By order of Mr. Grant I took down three or four or five declarations of his own men against Mr. Donald McKay, in consequence of which we took him prisoner for firing at Auge and laying in ambush for his life. I was his guard and slept with him at night.

Mr. Grant allowed Mr. McKay, le malin, to go home, seal his journal and write to his chief, Mr. McNabb. I went with him and, according to his promise, came back quietly with me. . . Finished marking Auge’s packs, 43.

Left River la Sourie after breakfast with 14 canoes and 3 boats. Mr. Grant thought proper to release Mr. Donald McKay, so we did not embark him, and he was so pleased with recovering his liberty that it was at his house we breakfasted by his particular request.” [2]

These entries clearly imply that Auge’s North West post and McKay’s Brandon House were in close proximity. This was a brief stop, yet Macdonell takes a declaration from McKay’s “own” men with little inconvenience. Further, they breakfasted at Brandon House on McKay’s invitation before embarking. This would have been impossible if the Hudson’s Bay post had been three or four difficult miles upstream.

The following winter, Robert Goodwin, who succeeded Donald McKay in the position of Post Master at Brandon House writes on 6 January 1795: “We are four houses here, and very little made at any of them yet.” [3]

With four posts in the Souris-mouth group, and with small establishments springing up elsewhere, these were days of keen competition and jockeying for strategic positions in which the men of the Bay not infrequently found that they were competing against themselves. The Hudson’s Bay historian, E. E. Rich, writes that Goodwin soon found that the outposts of York drew a certain amount of trade away from the area. This is an indication that Brandon House continued to be a child of the Southern Department traders from Albany throughout the 1790s.

In the fall of 1797, we find John Macdonell in charge of the North West Company post when David Thompson made it his base of operations for his winter expedition to the Mandan country. Thompson gives the location as Latitude 49.40.56 N. and Longitude 99.27.15 W. This latitude reading is less than a half-mile north of the large undisturbed site on the northeast bank, opposite the mouth of the little stream which Thompson called Five Mile Creek. The longitude reading is miles east, away from the river; but longitude was very difficult to establish accurately in Thompson’s day, for being a measure of the time interval between two points, his reading could be no more accurate than his timepiece. Thompson’s journal for November 28, 1797 states that as he left Macdonell’s house to begin their journey to the south and west, they crossed the Stone Indian River on the ice. This confirms the location as being on the northeast side of the Assiniboine. Thompson returned to this base on 26 February 1798. He had stayed there twelve days before setting out, and he remained twenty-three days after his return to work on his journals and maps. He refers to the gentleman in charge at this time as “my hospitable friend, Mr. John Macdonell, who furnished me with everything necessary for my long journey of survey.

A rift in the North West Company management in Montreal brought the X Y Company into being in 1798, at which time they also moved into competition in the Souris-mouth group. John Pritchard came from England to work for them about 1800, and we can be certain from his writings that the X Y post was on the south side of the Assiniboine. At about this same time, Donald McKay’s younger brother, John, was given charge of Brandon House.

There is a reference to these forts in the journal of the Nor’wester, Daniel Harmon, who was travelling east from Fort Alexandria on the upper Assiniboine in the spring of 1805. He writes:

May 27, Monday, Riviere a la Souris, or Mouse River. Fort Assiniboine, also known as Fort La Souris. Here are three Forts belonging to the North West, X.Y. and Hudson’s Bay Companies. Last evening Mr. Chaboillez invited the people of the other two Forts to a dance and we had a real North West Ball, for three fourths of the people were so intoxicated as not to be able to walk straight, the other fourth put an end to the Ball or rather Bawl! And this morning we were invited to breakfast at the Hudson’s Bay House with a Mr. McKay and in the evening to a Ball, which however ended in a more decent manner than the one we had the preceding evening at our House-not that all were sober, but we had no fighting.

It is now upwards of fifty years since a French Missionary left this, who had resided here a number of years to instruct the Natives in the Christian Religion. He taught them some short Prayers, the whole of which some of them have not yet forgotten.

May 30th, Thursday. In the morning I left Mouse River, and have along with me forty men in five boats and seven canoes. [4]

We can judge from this that the three forts were close neighbours, but a more positive statement is found in John Pritchard’s account of his adventure in the summer of this same year, 1805. Pritchard became lost on the Souris plains west and south of the fort, and a close reading of his account reveals several things. Confirming Harmon’s reference to three posts in 1805, we find that though the X Y and North West Companies had been reunited in the late autumn of 1804 their reunion had not yet been effected in the field. When Pritchard stumbles into the little wintering posts near Whitewater Lake, he thinks that they may be the Shell River houses and says: “There ought to be three, namely, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s, the North West Company’s and our own.” [5] A few days later he was rescued by a band of Indians, and writes:

“The next day the Indians took me to my fort, in the same way as I was drawn to their tents. On seeing my fort again I became senseless. They carried me into my room and you may suppose my people flocked about me ... Having recovered sufficient strength of mind I gave to each my hand and assured them nothing was amiss with me, that my intellects were as sound as ever and that I was weak from want of nutriment ... The news was soon at my neighbors. They and their men came running breathless to see me, my friend John McKay of the Hudson’s Bay Company (at B.H. a gunshot away) brought with him flour, sugar, coffee and tea with a couple of grouse and immediately set acooking himself as I believe the people were so transported that no one would have thought to provide for me.

Having taken a little refreshment they washed, shaved and clothed me. McKay dressed my feet and he became both my surgeon and my nurse.” [6]

Relevant to the precise location of the forts in this group Pritchard made one very significant remark-“at Brandon House a gunshot away”. One wonders also why he makes no particular reference to the North West Company’s house that Harmon had visited in May. Perhaps word of the reunion of the companies had reached the posts by the time he returned from his wanderings and the united group had consolidated themselves in the X Y buildings on the south bank of the river.

In any case, it is apparent that the North West Company were moved across to the south side by the following summer when Alexander Henry visited them in July of 1806. He writes under date of 12 July 1806:

July 12th, 1806 ... At two o’clock we proceeded and soon came to Montagne Diable the tops of which we had seen at Wattap River ... Having passed them we traversed a level plain for about 15 miles, when we arrived opposite our establishment of Riviere La Souris which is situated on the S. side of the Assiniboine. I was therefore under the necessity of applying to the H.B.Co. people to ferry us over, which they very willingly did. Their fort stands on the N. side where also ours formerly stood. The Gentlemen of the N.W.Co. are so fond of shifting their buildings that a place is scarcely settled before it is thrown up and planted elsewhere. The H.B.Co. people were busily employed making hair lines ... Mr. F. A. Larocque has this post in charge for the summer. [7]

Plainly the Nor’westers were on the south side. Perhaps they had moved into the newer buildings that had been occupied by the X Y Company. From Henry’s tone and reference to being “ferried across” it seems that the two companies were still in close proximity, though now the river ran between.

M. Francois Antoine Larocque was in charge of this south-side post in the fall of 1806. His account of the winter of 1806-1807 which he spent there is one of a secure and leisurely winter in which he took some pleasure; more particularly as “there were plenty of books at the place.” [8] In commenting oil the comparative strength of the two companies in this area, as such could be measured in the spring of 1807, he notes that Thomas Vincent of the Hudson’s Bay Company had fifty-three men in his service while he had fifty-two women and their families to support and not enough men to furnish a bare subsistence for so great a number.

Apparently it was decided that a move was in order for the North West Company. Larocque writes:

“In May (1807) I had the house demolished, also the store buildings which were not absolutely necessary, and had them transported on rafts to a place named Pine Fort, situated approximately thirteen miles down the river, conforming to Mr. J. McDonnell’s instructions, who had decided to construct a fort at this place and to demolish the one in which I had spent the winter. I employed all the men that I could spare to rebuild the store buildings and, when I left that place, everything had been transported to the new fort and put under shelter ... I left Pine Fort on the 3rd of June in company of Mr. Charles McKenzie and embarked with Mr. McDonnell to go to Kaministiauia, having the brigade with us.” [9]

The first Pine Fort had been abandoned shortly after Auge was established at the new location in the fall of 1793, and now it was to be restored to activity.

Thus, by the summer of 1807, the Hudson’s Bay men in the well staffed, well-stocked post which Larocque described, are, for the first time, the sole traders on the Assiniboine in the Souris-mouth area.

For this period (1807-1814) there seems to be a gap in the available written records. There was little reference to this area until 1814 when Spencer tried to enforce Miles Macdonell’s pemmican embargo against the North West Company’s Fort Souris of that day. However, a page by page examination of the Selkirk Papers revealed a journal which had not been studied previously, at least not in relation to its bearing on the location of Brandon House. The clerk who copied it from the original had headed it simply “Journal of Red River” and it was entered under this heading in the Calendar of the Selkirk Papers. It appeared in the Index under the “Y’s” - “William Yorstone, Journal of Red River, pp. 16,500 - 16,542”, and was nowhere identified as a Brandon House Journal. I found it when reading the journals of Colin Robertson, Rogers, and Miles Macdonell.

With all the unanswered questions concerning the Souris-mouth forts, it was an exciting discovery. William Yorstone was the man in charge at Brandon House in mid-May of 1810 (when the journal begins), at which time, the post master, John McKay, lay dying. McKay’s death and burial are duly recorded in the entries for 5, 6 and 7 July. Yorstone continued in charge of the post; and his daily journal, faithfully kept, continues until 23 May 1811 when the Selkirk Papers copy ends. It provides a rich source of information relative to Brandon House and its hinterland in these years.

From it we learn that the North West Company did not return to compete in the area until sometime after the spring of 1811, but remained at their Pine Fort location to which Larocque had transported them in 1807. This post is mentioned frequently in this 1810-1811 Brandon House Journal, and their gregarious Mr. John Pritchard was a visitor at Brandon House on several occasions. The rival companies seemed to enjoy an era of peace and co-operation in these years, for a Hudson’s Bay official for the district wrote directing the men at Brandon House to have some work done by the blacksmith at Pine Fort, as the Nor’westers owed them a favour.

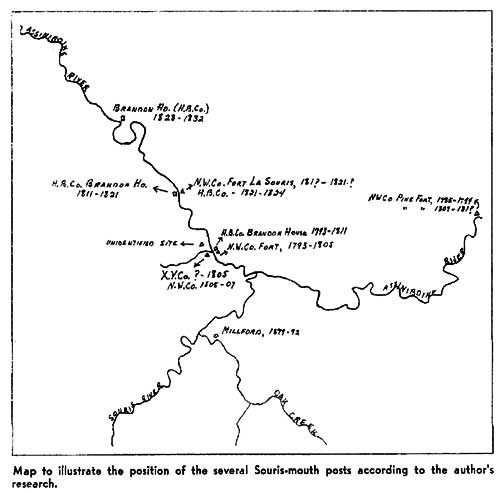

For purposes of clarifying the proper location of the site of the Brandon House of 1816, this journal is of the utmost significance; for in it we have a detailed account of a move upstream and across the river which took place in the spring of 1811. There are many references to moving buildings, ferrying supplies, and to men making bales at the “old house” or laying out new buildings at the new. It would seem that this journal does, in fact, give a full account of the move from the original location on the north bank opposite the mouth of Five Mile Creek, to the big site in Morgan’s field-more than three miles upstream, and on the southwest bank. This would mean that the North West Company’s Fort La Souris of 1816 must have occupied the site on the northeast side of the river that was for so long believed to have been the site of Brandon House from 1793 to 1818. [10]

Dr. Stewart interpreted Peter Fidler’s reference to Brandon House in his report of 1819 to mean that the fort had been moved across the river to the south side after their trouble with the Nor’westers in 1816 prior to the battle at Seven Oaks: but with our new knowledge of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s move to the south side in 1811, we have no difficulty in accepting Fidler’s account at face value. He means exactly what he says when he writes: “Brandon House - 6 miles above the Souris River on the south side ...” [11] In providing further details about the establishment, he says that it is in “a ruinous state occasioned by the war brules in 1816”, [12] and goes on to say that “a small new house was built here last summer 30 x 14 ft. There are a smith and coopers shops also a trading room, provisions stores and 2 stables with houses for men and Indians when they came to the Houses to trade.” [13] If we consider the “small new house” in its context, as an item listed as one of a considerable group of shops and houses, it is apparent that the words refer to a new building only. If there is any doubt of this, the dimensions, 30 x 14 feet, are certainly those of a building, not a complete trading establishment.

Map to illustrate the position of the several Souris-mouth posts according to the author’s research.

Perhaps, the most definite and conclusive evidence concerning the exact location of Brandon House in 1816 is to be found in Peter Fidler’ deposition on its capture by the Nor’westers as a prelude to Seven Oaks:

“That on the evening of the 31st day of May last 1816, Alexander Macdonell, a partner of the North West Company accompanied by Several Canadians and men commonly called halfbreeds (that is the sons of Canadians by Indian Women and born in the Indian Countries) arrived at the Trading house of the North West Company called Riviere la Sourie, and situated opposite Brandon House at the distance of about two hundred yards. That on the following morning a body of about 48 men composed of Canadians, Halfbreeds and a few Indians armed with Guns, Pistols, Swords, Spears, and Bows and Arrows, appeared on Horseback in the Plain near to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trading house (called Brandon House) of which he the deponent was then Master and Trader for the said Hudson’s Bay Company, that this body of men, beating an Indian drum, singing Indian Songs and having a Flag flying rode towards the North West Company’s trading house, that on a sudden the said body of men turned their horses and rode on a gallop into the yard of Brandon House, where they all dismounted, erected their flag over the gate of the house and deliberately tied their horses to the stockades. That then Cuthbert Grant, a halfbreed and clerk in the service of the North West Company who appeared to be the leader of the party come to the Deponent and demanded the keys of the House that on the deponent refusing to deliver up the keys, a halfbreed called McKay (son of the late Alexander McKay formerly a partner of the North West Company) assisted by several of his companions broke open the doors of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Warrehouse and plundered the property consisting of trading goods, furs and other articles to a considerable amount, which together with two boats belonging to the H.B.Co. they carried away. The deponent further saith that when the said McKay and party had finished plundering the Houses of the Hudson’s Bay Company the whole body of Canadians, halfbreeds and Indians, crossed the River and went to the North West Company’s House taking with them the plundered property ...” [14]

In another document Fidler describes the events of the first of June in slightly different terms and with some additional details which are very conclusive in determining the positions of the forts of the taco companies:

“At half past noon about 48 halfbreeds, Canadians, Freemen and Indians came all riding on Horseback, with their flag flying blue about 4 feet square and a figure of 8 horizontally in the middle, one beating an Indian drum, and many of them singing Indian songs, they all rode directly to the usual crossing place over the river where they all stopped about two minutes, and instead of going down the bank and riding across the river they all turned suddenly and rode full speed into our yard-some of them tied their horses, others loose and fixed their flag at our door, which they soon afterwards hoisted over our East Gate next the Canadian house—Cuthbert Grant then came up to me in the yard and demanded of me to deliver to him all the keys of our stores warehouses and I of course would not deliver them up—they then rushed into the house and broke open the warehouse door first, plundered the warehouse of every article it contained, tore up part of the cellar floor and cut out the parchment windows without saying what this was done for or by whose authority—Alex. McDonell, Serephim, Bostonais, and Allan McDonell were at their house looking on the whole tune ...” [15]

For our present purpose the significant references here are, “over our East Gate next the Canadian House”, and “... were at their House looking on the whole time.” These references definitely place the 1816 Brandon House at the big site in Morgan’s field, and the North West Company’s Fort La Souris on the high bank east of the river, at the site that has been known as Brandon House No. 1.

We do not know in what year the Nor’westers abandoned Pine Fort for the second time, and moved back to compete in the Souris Assiniboine area; but whenever it was, they placed their new fort at the top of the high bank immediately across the river from the Hudson’s Bay Company’s new establishment. This choice of position was in accordance with the long established policy of keeping their rivals under constant surveillance wherever possible, and the fact that they had to build a corduroy road to reach solid ground on the landward side did not deter them.

These corrected locations correspond with the evidence of the existing maps which previous research tried to reconcile with the assumptions made. Lewis and Clark’s map (circa 1804) shows Brandon House in its original downstream location on the northeast bank, where it was when their men visited the area.

In the map prepared for Lord Selkirk to illustrate the District of Assiniboia it is shown on the north side, as this map was published in 1811, about the time of their move across to the south bank, and was based on earlier information. The first map to be published after Yorstone and his men had established Brandon House at its new location was that of William Sax, a surveyor. His map was published in 1818 and shows Brandon House correctly on the south side, as does Peter Fidler’s somewhat diagramatic and topsy-turvy map that accompanied his report on the Hudson’s Bay posts in 1819.

After the amalgamation of the companies, Chief Factor John McDonald reported that Brandon House operated on the north side of the river from 1820 to 1823. It seems from this that when the companies united, they moved into the North West Company’s buildings which may have been more serviceable and better preserved, or more in keeping with the amount of business that was then being done in the area.

Their tenure in this north-side location was brief, for by 1824 Brandon House was closed out as part of the retrenchment which followed amalgamation. Thus ended a trading existence of some thirty-one years in the Souris-mouth district. Another north-side post bearing the name opened briefly five years later, but it was almost ten miles farther up the Assiniboine on Section 29-9-1 W1.

In the matter of site identification one major problem remains. Where exactly was the first Brandon House? And where was the original North West Company post that stood nearby on the same side of the river? Where indeed was Ranald Cameron’s post or the other small posts that sprang up briefly before the turn of the nineteenth century?

At the place where the early group clustered only one site is clearly identifiable on the north side, although there are two known locations on the south side. This single north-side site is large, long-used, well located, undisturbed, and comparatively little-decayed o; overgrown. Whose fort was it? From a comparison of the size of the founding parties as they are reported in John Macdonell’s journal, we can see that Brandon House was almost certainly larger from the outset, and from Larocque’s comments it was larger and better staffed in 1806-1807 when Macdonell ordered the Nor’westers to pull out and relocate at old Pine Fort.

Further, this first Brandon House was in full-time operation for eighteen years, while the original North West Company establishment was active for only fourteen years. Also, this big site could very accurately be described as being “a gunshot away” from the site that fits the description of John Pritchard’s X Y post. There is also the probability that the original Brandon House site was not completely abandoned even by 1816; for in that year Peter Fidler refers to a buffalo robe being brought from the “old house”. From such accounts, which suggest greater size and indicate longer occupancy, one would expect the surviving traces of the first Brandon House to be more in evidence than those of the first North West Company post.

It would seem that the big site opposite the mouth of Five Mile Creek, that has always been thought to be the first North West Company post (sometimes called Fort Assiniboine), is actually the site of Brandon House No. 1, which leaves us with the problem of someday: determining the exact ground on which the original Nor’westers’ post stood. Or if the foregoing speculation is wrong, in spite of supporting evidence, and this large site was of the North West Company, where then was the first Brandon House? David Thompson’s latitude reading [16] places the North West fort about a half-mile north of this site; but I am told by an authority in the Surveys Branch that a deviation so slight occurred frequently with the primitive equipment which he had to use. If the posts were very close together, which is quite possible, the traces of a stockade on the lower ground one hundred yards east and south of the big clearing may indicate that Fort Assiniboine occupied this spot.

It would seem that the whole area is a fruitful field for archaeological investigation, for there is ample evidence that here was an important point-of-pause in the Indians’ yearly migrations; and it was certainly one of the original centres of fur trade activity in the plains area of Manitoba—one that was active for some twenty years before the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine came into prominence.

1. Grace Lee Nute (ed.) Journal of John Macdonell from Five Fur Traders, published for Minnesota Society of the Colonial Dames of America (University of Minnesota Press, 1933), pp. 109-111.

2. David A. Stewart, “Early Assiniboine Trading Posts of the Souris-mouth Group - 1785-1832”, Transaction No. 5 (New Series). The Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba (1930), p. 10.

3. Ibid., p. 14.

4. W. Kaye Lamb, (ed.) Sixteen Years in the Indian Country, The Journal of Daniel Williams Harmon (Toronto, 1957), pp. 89-90.

5. Martin Kavanagh, The Assiniboine Basin (Winnipeg, 1946), p. 52.

6. Ibid., pp. 52-53.

7. Eiliot Coues (ed.) New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry and of Darid Thompson, 1799-1814, I, (New York, 1897), pp. 297-298.

8. Journal de Larocque (Francois Antoine), translated by L. J. Burpee, F.R.G.S., 1911, p. 74.

9. Stewart, op. cit., pp. 22-23.

10. Both of these fort sites are located on the N.E. 1/4 35-8-17 W. 1st.

12. Ibid., p. 34.

13. Ibid., p. 35.

14. P.A.M., Selkirk Papers, p. 15,900.

15. Margaret Arnett MacLeod and W. L. Morton, Cuthbert Grant of Grantown (Toronto, 1963), quote of H.B.C.A. B/22/A119.

16. David Thompson’s latitude reading for this fort was (49.40.56 N).

Page revised: 9 August 2014