by Charles W. Bohi and H. Roger Grant

Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1978, Volume 23, Number 3

|

Small-town railroad stations are no longer critical to the transportation needs of Manitobans. Observant individuals can easily find abandoned and decaying depots dotting the provincial landscape. This, however, was not always true. Before rubber-tire vehicles gained their current degree of dominance over flanged-wheel ones, the railroad station held special significance for most residents. Of all the regions of Canada, railways were once most vital to the Prairie West. Farmers were nearly totally dependent on them to market their bulky crops; few had access to water arteries. Merchants and citizens of the ubiquitous "false-front" towns similarly relied on the railroad for their commercial and personal needs. The "deepo" undeniably served as the gateway to the world. Visitors, in fact, regularly judged a community by the appearance of its station a flimsy wooden building likely meant a struggling village while a commodious brick one gave tangible evidence that a town had come of age.

The overall objective of this photographic essay is to examine the most common small-town or "country" depot styles in Manitoba. While railroads built these largely inexpensive structures from standard plans, they were unquestionably functional and often attractive additions to the architectural milieu. [1]

The most important purpose served by small-town depots was to provide railways with a place to offer their services. Passengers could buy tickets and have a comfortable setting in which to wait. Freight and package express could be stored until they were loaded onto trains or delivery drays. Local industries, especially grain elevators, could order freight cars and have them billed for shipment. Telegrams, whether personal or business, could be sent or received. Not only did the depot serve as an economic centre but it became a popular place for local socializing. "Loafers" were regular fixtures in country depots.

A less obvious function of depots and agents was to assist in train control. By having agents report freight and passenger movements past their stations and by using these employees to relay orders to crews, dispatchers could plan meeting and passing points. Thus, even if there were few local customers, depots were still needed for the safe operations of a railway.

In the small agricultural communities of Manitoba transportation needs could be easily met by erecting a "combination" station. By providing space for a waiting room, office, and freight house under a single roof, construction costs could be minimized. Few communities in the province ever grew to the point where separate (and presumably custom-designed) freight and passenger stations were justified.

Since agents often found housing difficult to find in Manitoba's rural hamlets, the companies generally included living quarters in their combination depots. Usually this was done by adding a second storey and rear annex. This extra investment was thought worthwhile: carriers considered married agents more responsible and better representatives than single ones, and occupied buildings lessened vandalism and burglaries.

Since railway building was expensive, it followed that the cost of station construction must be kept low. Consequently, most Manitoba depots were built to standard plans, though companies made their blueprints sufficiently flexible to allow variations to meet local needs. Wood was almost universally used, although the Canadian National frequently gave their depots a coat of stucco. Wooden or cinder platforms rather than more expensive brick or concrete typically adjoined stations. Indoor plumbing, central heating, and electricity were amenities that waited for later remodelling, if indeed they ever came to a majority of Manitoba's depots. Stations generally lacked insulation when initially constructed, a surprising omission considering the region's climate.

So cost conscious were the railways that the first depots in most hamlets were primitive portable ones, designed to be transported to a site on a flatcar. These cheap buildings made it possible for a serviceable structure to be installed quickly and inexpensively when a line opened. If traffic grew, a more elaborate and, of course, permanent station would be erected.

During the formative years of railroad construction even the larger buildings that replaced the portables were Spartan. Not until the turn-of-the-century did the railroads of Manitoba give careful attention to making depots attractive as well as functional.

The desire to have more impressive structures is likely related to political and competitive pressures. Until the 1890s the Canadian Pacific (CP) enjoyed a virtual transportation monopoly in Manitoba, but not always the friendliest relations with patrons. By 1900 the company had become so unpopular with the shipping and traveling public because of high and discriminatory rates and alleged poor service that demands for competitive lines and for tough regulation developed. No doubt, too, many communities had been dissatisfied with what they perceived as inadequate facilities. No town wanted an unattractive station to serve as its entrance. As consumer unrest grew and as competing railroads invaded its territory, it is understandable that the Canadian Pacific thought the investment in more architecturally pleasing depots worth the expenditures.

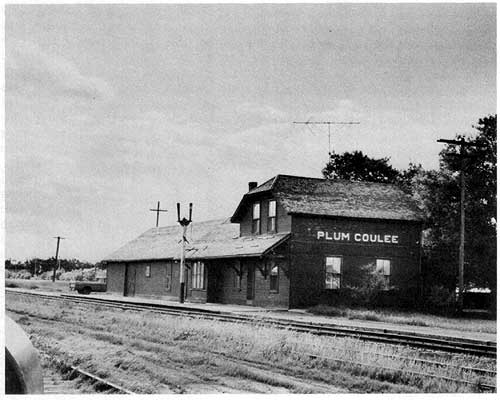

One of the first in a series of "new breed" combination depot designs employed by the Canadian Pacific is typified by the station at Plum Coulee. Characterized by a gambrel roof on the second floor with a gable one covering the freight house, this structure has a bracket-supported shingled awning along the trackside front. This incidentally serves a practical function: conceived of for temperature control, the awning not only gives protection against inclement weather, but it provides shade during the hot summer months while still allowing the low winter sun to shine through the windows. Clearly, this type station would be more acceptable as a community gateway than a small portable, or one of the simple depots used by the road in the late nineteenth century. Six Plum Coulee-like buildings remained in Manitoba as late as 1970, while other examples are located in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

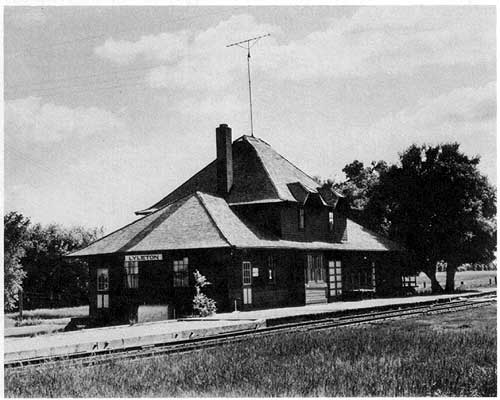

An even more ornate and regular combination station design adopted by the Canadian Pacific about 1900 is represented by the Lyleton depot. Appropriately labelled "pagoda" style, it boasts a hip roof over the first storey and a bellcast one tops the second. Broken by hip-gable dormers, the upper floor contains tiny decorative dormers on its peak. The CP erected seventeen of these handsome stations in Manitoba; more appeared in Saskatchewan.

After World War I an intense struggle erupted between the Canadian Pacific and the newly created Canadian National system. Thousands of miles of new trackage opened in Western Canada, and each carrier formulated fresh depot designs. Since the agricultural regions of Manitoba were already well-supplied with railways, few additional lines appeared. Yet, both companies constructed new stations in the province, most being replacement ones. The styles used along new routes for example those in southern Alberta - frequently were also employed in Manitoba.

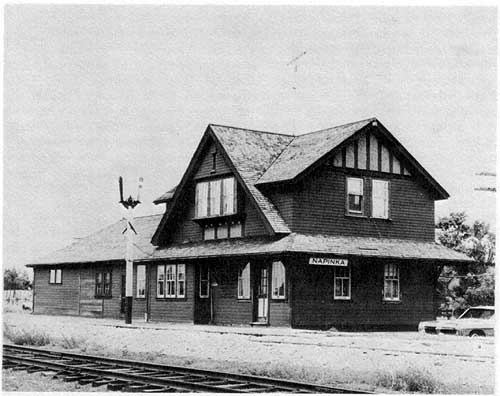

Typical of Canadian Pacific depots constructed in Manitoba between 1918 and the late twenties is the one at Napinka. Covered by a gable roof, the front is dominated by a massive gable dormer and a large bay. A large shingled awning that runs along the front and around the waiting-room end heightens the structure's imposing appearance. This awning even extends along a portion of the rear of the station. At least fourteen of these striking depots were erected in Manitoba and more in Saskatchewan and there may have been additional examples in Alberta. No doubt citizens proudly welcomed these structures.

The Canadian Pacific owns a richer variety of standard station designs than any other railway in Manitoba. This can be explained in part by the fact that the CP constructed its lines over a much longer time period than did the others. Between the 1880s and 1930s - the era of greatest railroad building in Western Canada - there was ample chance for depots to wear out, be destroyed by fire, windstorm, or some other means, or for management thinking about design to change. Furthermore, the Canadian Pacific absorbed smaller firms that had their own notions about station planning. By mid-century depot styles had become thoroughly mixed along the CP system.

In Manitoba the first important competitor of the Canadian Pacific was the Canadian Northern (CNoR). [3] Headquartered in Winnipeg, this road, spearheaded by promoters William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, emerged as a major rail operation after 1901. Aptly described as a "colonization" railway, the CNoR pushed into areas that had good traffic potential. These construction policies allowed the firm to open up virgin areas quickly and, more importantly, to lower over-all freight charges. Consequently the Canadian Northern competed successfully with the Canadian Pacific, and it became popular with Manitobans. With financial backing from the province, the CNoR constructed most of what is today the Canadian National. Similar support in other provinces helped to develop the company into a transcontinental system. Overextension, however, led to nationalization in 1918.

Like the Canadian Pacific, the Canadian Northern experienced a period of experimentation in its depot-design policies. Manitoba, where the company's original lines appeared, contained a richer variety of CNoR stations than did the other Western provinces. Nevertheless, the Canadian Northern's depots in Manitoba were more standardized than those of the CP. Since the CNoR built most of its lines between 1900 and 1914, there was much less time for changes in depot design to occur. This is probably the best explanation why the CNoR owned a smaller collection of standard depot styles than did its older competitor.

In the early years of the twentieth century the Canadian Northern carefully systematized its depot plans. As part of this process the carrier adopted a design that was to be used for nearly half of its 134 stations in Manitoba. This widely used plan, designated "Third Class" by the CNoR, became so commonplace that it emerged as a virtual trademark of the road. [4]

Although having several variations, sixty-two "Third-Class" station buildings were employed in Manitoba. All share common identifying characteristics. The most important is an unique roofline. With its steep-pitched roof broken front and back by prominent gabled dormers, the "Third-Class" depot is an impressive affair. Over the baggage room is a gabled roof that flows down toward the front to form part of a bracket-supported shingled awning. Under the awning is a rectangular bay with a lone trackside window. All these features create a symmetrical and visually pleasing structure that must have done much to harmonize relations between the Canadian Northern and its patrons.

An early and popular version of the "Third-Class" depot is officially known as plan "100-3." This particular style has a pyramid roof and no windows on the front of the waiting-room end. These structures, with outside dimensions of 42'x22', were shorter than the later ones. The initial length proved unsatisfactory for most of these depots have additional space added to their freight houses. The road erected twenty-six of the "100-3" buildings in Manitoba. (See Piney photo) Others are in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

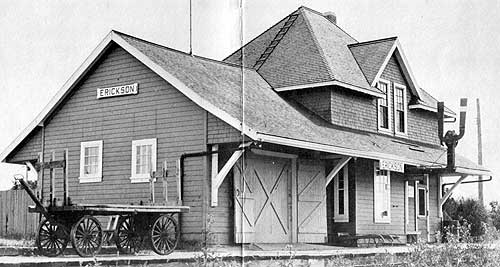

In 1907 the Canadian Northern modified its "Third-Class" depot to produce plan "100-29." The new drawing provided a building measuring 46'x22', four feet longer than the prototype. The extra length may explain the employment of a hip rather than a pyramid roof. To light the waiting-room end, company architects added a front window between the public door and the bay window. (See Erickson photo)

Unlike the Canadian Pacific and the Canadian Northern, the last large privately owned railway built in Manitoba, the Grand Trunk Pacific (GTP), did virtually no experimenting with its station plans. [5] Also absorbed by the Canadian National, the GTP was a subsidiary of the Grand Trunk, a company with a vast system in Ontario and Quebec. Designed as a mainline, the Grand Trunk Pacific lacked an extensive network in Manitoba. It erected nearly all of its depots in the province between 1909 and 1912. No other railroad constructed its stations in such a brief period. It is little wonder that a high degree of standardization should occur. [6] Of its twenty combination depots in Manitoba, twelve were constructed from an identical blueprint.

While none of the twelve survived until the 1970s, the former Grand Trunk Pacific station at Estlin, Saskatchewan is of the same design. The depot features a bellcast hip roof, a hexagonal bay window that continues through the roof to become an unique dormer, and a single window on each end elevation. While exterior dimensions varied, the plan for the Estlin structure called for a length of 51' 6" and a width of 16'. Wide roof overhangs and the shape of the bay window, however, make the structure seem wider. Even this small station contains space for the agent's living quarters. The upstairs dormer illuminates two bedrooms, and a rear addition houses a kitchen. All the Western provinces as well as Ontario and Quebec once had sizable numbers of these stations.

Time has not been kind to Manitoba's country depots. By the 1970s most were no longer needed. Economic and technological changes allowed railway companies to retire scores of stations. While this is understandable, it must be remembered that these depots once throbbed with life and were crucial to the communities served. It is hard not to feel a sense of loss as more are removed or converted to non-railway uses. Attempts by individuals to save these fine old buildings means that a significant portion of Manitoba's architectural heritage is being preserved.

1. The complete story of the small-town railroad station in Manitoba remains to be written. However, Charles W. Bohi, Canadian National's Western Depots: The Story of Canadian National Railway Stations from Western Ontario to the Pacific (Montreal: Railfare Enterprises, Ltd., forthcoming 1978), offers the best coverage of CN system depots in the province.

2. For accounts of the development of the Canadian Pacific see: W. Kaye Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (New York: Macmillan, 1976); Omer LaValle, Van Horne's Road (Montreal: Railfare Enterprises, Ltd., 1975); Pierre Berton, The Impossible Railway: The Building of the Canadian Pacific (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972); Harold A. Innis, The History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (London: P. S. King and Sons, Ltd., 1923); and J. L. McDougall, Canadian Pacific: A Brief History (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1968).

3. Professor T. D. Regehr of the University of Saskatchewan has written the leading studies of the Canadian Northern. See his "Serving the Canadian West: The Canadian Northern Railway," The Western Historical Quarterly, III (July 1972); pp. 283–298 and his The Canadian Northern Railway: Pioneer Road of the Northern Prairies, 1895-1918 (Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd., 1976).

4. The Canadian Northern developed a host of variations to the basic "Third-Class" plans, yet two styles emerged as the most common: "100-3" and "100-29."

5. The story of the Grand Trunk Pacific is treated in the studies of the Canadian National. See, for example, Henry E. Hewetson, The Financial History of the Canadian National Railway (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1940); and G. R. Stevens, History of the Canadian National Railways (New York: Macmillan, 1973).

6. While the Canadian National developed standard plans for its depots, few were built in Manitoba.

Note: The authors wish to thank the Audio-Visual Department of The University of Akron for its assistance in the preparation of this article.

Page revised: 20 July 2009