Manitoba Pageant, Autumn 1967, Volume 13, Number 1

|

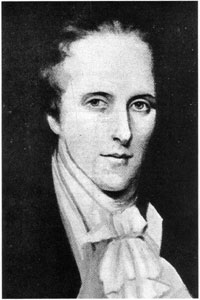

Lord Selkirk

1771-1820

In Scotland during the latter part of the 18th Century a great many changes had taken place. The Clan system was gradually giving place to a more modern land tenure. The people at this time could be divided, generally speaking, into three classes—the landowner, the middleman and the sub-tenant who held land under the middleman paying rent to him, while the middleman in turn paid rent to the land-owner and when called upon gave military service. After the rising of 1745 and the general opening up of the country that followed, with a subsequent rise in the price of land, cattle and sheep, the landowners began to improve their own position by dispensing with the services of the middlemen, drawing rentals direct from the sub-tenants who were for the most part their clansmen. This action on the part of the landowners caused the first great migration to America, the middle-men, bereft of home and livelihood, leaving the country in great numbers, often taking with them a group of their fellow clansmen who were only too willing to migrate and thus improve, they hoped, their own living conditions. It is recorded that over two thousand Highlanders left Scotland for the northern United States, Prince Edward Island and Glengarry County during the years 1773-1786. This resulted in large tracts of land being almost depopulated and in turn gave rise to the influx of sheep farmers from the Lowlands. In areas to which they came the few remaining tenants were gradually driven out, some-times forcibly, their homes and buildings burned, their cattle run off or ruthlessly slaughtered.

At this period the only means of obtaining land abroad for settlement was for some wealthy person to purchase land from the Crown and be responsible for the placing thereon of suitable settlers, who in turn purchased land from the holder of the grant, paying him in cash, cash and improvements, or as in the case of the military settlements in Ontario at a reduced price in recognition of military service. In the case of the Red River Settlement Lord Selkirk purchased the land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, who at that time held all of Rupert’s Land under their Charter of 1670, granted by Charles II. This then was the condition of the Highlands when Lord Selkirk began his great work of colonization.

Thomas Douglas, seventh son of the fourth Earl of Selkirk, was born in 1771, and after the deaths of his elder brothers succeeded to the title in 1797. As a young man he had travelled extensively and had become interested in colonization as a means of helping his fellow countrymen who were being forced out of their homes in the Highlands. As early as 1802 there is a reference in one of his letters to Lake Winnipeg as a district suitable for an inland settlement, but no Government aid was forthcoming, and it was not until after his marriage to Jean Wedderburn-Colville, in 1808, that he began to purchase Hudson’s Bay Company stock. The Colville family had for years been large stock holders and it was through their interest and his own large holdings that he was able to obtain control of the Company and in 1811 was able to arrange for a grant of 116,000 square miles at Red River, extending from the height of land in the south to midway up Lake Winnipeg, and from west of Lake Winnipegosis in the west to the Lake of the Woods and the Winnipeg River in the east.

For some years previous to this the Hudson’s Bay Company had done little in the way of inland development, trade was confined to the posts around Hudson Bay and the Company seemed content as long as the Indians brought their furs to the Bay each spring. On the other hand the North West Company, with headquarters in Montreal, was steadily extending its trade, the “wintering partners” going inland each season carrying trade goods to the Indians in the far West, each spring bringing out the winter’s furs, by canoe to Fort William, thence to Montreal. Chester Martin in his Lord Selkirk’s Work in Canada, has said “for keen, hard, shrewd efficiency, the North West Company was perhaps the most terribly effective organization that has ever arisen in the New World”. Alexander Mackenzie, Edward Ellice and many of the North West directors held large blocks of Hudson’s Bay Company stock and, as the rivalry between the Companies grew, were able to cause much of the “delaying action” that was so nearly fatal to Lord Selkirk’s plans. Repeatedly when the Settlers reached their embarkation port there were delays caused by lack of ships, shortage of officers and men to man the ships, last minute crew desertions, pettiness on the part of the Customs officials. Practically all these troubles could be traced to North West influence, either in London or at the Northern ports.

Many historians have put all the blame on Lord Selkirk for the apparent failure of the Settlement in the early years, yet if his instructions had been carried out, as he had every reason to believe they would be, the first Settlers arriving at Red River would have found homes and farm buildings awaiting them, gardens and crops ready to harvest, and in the Colony storehouses food supplies, clothing and implements sufficient to tide them over until they could become self-supporting. Selkirk’s plans were not impractical as the ultimate success of the Colony shows. They were not carried out by the men responsible.

With the passing of years it is easy to see the other side of the picture. The rival companies were close to open warfare when the first Settlers arrived to be given land and build homes at the very heart of the North West Company trade routes. The majority of the fur trade men, of both companies, were opposed to a Colony of any kind, realizing that the opening up of the country for settlement would be the end of the fur trade. Many of the Hudson’s Bay men felt that Lord Selkirk should not have used his controlling interest in the Company to promote settlement in a region heretofore strictly fur trade country, especially at a time when the North West Company was doing every-thing in its power to break the Hudson’s Bay Company monopoly, and the Company was just beginning its western drive for increased trade. These men knew, perhaps better than Lord Selkirk possibly could, how much the Settlement at Red River would interfere with the gathering of furs and the transporting of trade goods, which was after all their business and livelihood. While these feelings were general throughout the fur trade there were traders and factors, both at Red River and at the Bay, who were always ready and willing to help the Settlers, especially men with native families who looked forward to retirement when they could take up land at Red River and make a home for themselves and their families.

Lord Selkirk was no mere dreamer, as one can readily see as more and more diaries, letters and Company records are made public, and one cannot help but realize the care with which each and every move was planned. If only the plans had been carried out as he instructed what a different story there would be to tell; as it is we can only marvel at how much he did accomplish in spite of opposition on every hand and his increasing ill-health.

His first Colony was in Prince Edward Island and was highly successful. The next venture was at Baldoon, in Western Ontario, and was abandoned during the War of 1812. He then turned to Red River, an ideal place for settlement, far inland from the Bay, in virgin country, it would shortly be self-supporting, and lastly but all important it would be a bulwark of the British Empire. The Settlers were to pay £10 sterling per head and in return would receive their transportation, 100 acres of land at 5s. per acre, and one year’s provisions. Markets for surplus crops would be established through the Hudson’s Bay Company. There would be a Presbyterian Church with a Gaelic speaking minister, schools and schoolmasters, mills, bridges, roads and an experimental farm. It was realized that the Settlers could bring little with them owing to the difficulties in transporting goods from the Bay but once established at Red River they would be short of nothing. This was no charitable gesture on Lord Selkirk’s part as is frequently suggested, it was a “strictly business” proposition. These people were not destitute. Records in Scotland show that in 1799 a collection was taken up called the National Emergency Fund and the Parish of Kildonan averaged 6s. per head, which was a lot of money in those days. Again in 1813 they offered to raise a sum equal to the highest bid by the sheep farmers as annual rent plus £500 sterling, again a lot of money. However, the landowners wanted to clear their lands and bring in sheep so the tenants were forcibly driven from the land that for generations had been farmed by their family or Clan.

Capt. Miles Macdonell, the first Governor of the Settlement, was born in Scotland and at the age of nine moved with his family to the northern United States. During the Revolutionary War he, together with his father and older brothers, fought with the Loyalist Army and at the end of the War came to Canada and settled in the County of Glengarry. An elder brother, John, was for years with the North West Company in the West and it was through letters from John that Miles was able to give Lord Selkirk information about the Western prairies. When Lord Selkirk was ready to send settlers to Red River he wrote to Miles Macdonell, asking him to come to London and to take charge of the party of workmen going out to prepare the settlement for the Settlers who would arrive the following year. While in England, just before leaving for Stromness to sail for Rupert’s Land, he was presented with his commission as Governor of Assiniboia. In his Journal he tells of his meeting with Lord Selkirk in London, of the plans for the working party, of their trip north to Stromness, of the difficulties met with there, of the trip to York Factory, the winter at the Bay, the trip inland next spring (1812) and his eventual arrival at The Forks. In fact his Journal is a day to day account of all the worries and frustrations met with on the trip, culminating in his arrival at the Forks to find none of the promised supplies awaiting him. But over and above all his worries he tells a most interesting and entertaining story of the country through which he passed, the few Company men and Indians met enroute, their camps and portages, even the weather, trees, flowers, wild fruit and the birds are all reported on. As told in his Journal there were delays at Stromness before they were able to set sail on 26 July with one hundred and twenty men, the ship was poorly officered and manned, and added to this they ran into very bad weather and it was 24 September before they landed at York Factory, too late to make the inland trip before freeze-up. Governor Auld, who never willingly helped the Settlers and who eventually was discharged and later joined the North-west Company, and W. H. Cook, who was always friendly and willing to help, chose a campsite for the party twenty-three miles up the Nelson River, and there in huts built Canadian style under the direction of Miles Macdonell, the winter was spent in hunting and fishing and when supplies were available in building York boats for their inland trip. Many of the men were troublemakers, quarrelsome and quite unsuitable for the work they were called on to do. By spring it was decided that a number of them would have to be returned to the Old Country, while others transferred to the Company service, so that by the time the party was ready to leave for Red River there were only thirty-five left of the original one hundred and twenty. Making the best of it they left in three boats and a canoe and reached The Forks on 30 August 1812. Camp was made at the Company stores depot on the East side of the Red River, not far from where St. Boniface Hospital now stands, and directly across the river from the North West Company’s Fort Gibraltar. There on 4 September Governor Miles Macdonell, with all formality, took possession of the land granted to Lord Selkirk by the Hudson’s Bay Company. He tells us that the Patent was read in the presence of the Governor’s party, a few Canadian freemen and Indians, and three Northwesters who immediately reported proceedings to their headquarters at Fort William.

At this time in writing to Lord Selkirk he says,—“the country on the west side of the river is all plain with a belt of woods on the river’s edge of irregular depth, the east side is well wooded, oak, elm, cottonwood, ash and maple, there is no pine or cedar. The country exceeds any idea I had formed of its goodness, I am only astonished it has lain so long unsettled. With good management buffalo in winter and fish in summer are sufficient to subsist any number of people until more certain supplies are got out of the ground. The river has amply fed us and about 200 people in the neighborhood since the beginning of June. The land is most fertile and the climate most extraordinarily healthy, the fever and ague so prevalent in other parts of America is here unknown.”

As soon as the formalities were over the Governor set about preparing for the coming of the Settlers. The land chosen was on the west side of the Red River north of the point of land that we know today as Point Douglas. This land was comparatively clear of timber, a bad fire having burned over it some years earlier, and this would, of course, enable the Settlers to get their land broken and crops in with a mini-mum of labor. The farms were 100 acres, facing on the river, running back two miles with another two miles as a “hay privilege,” and directly across the river each Settler was granted a wood lot, where timber could be cut for his own use. Timber was cut for homes and farm buildings as well as for the Colony Fort, which was located at the base of the Point, south of the Settlement.

Isaac Cowie in his Company of Adventurers tells us in detail of his trip from the Bay to Red River over the famous Hayes River Route, and although he came over it at a much later date (1867) it was the same route used by fur trader and settler alike when travelling between the Bay and the Forks. It was four hundred miles from York Factory to Norway House (Norway House replaced the earlier Jack River Post) with an ascent of seven hundred feet. There were thirty-four portages varying in length from sixteen to seventeen hundred and sixty yards, over which cargoes and sometimes the boats themselves had to be carried. On leaving York Factory the route followed the Hayes River to the forks of the Shamattawa and the Steel, up the Steel to the forks of the Hill River, up the Hill River and through Knee Lake and Oxford Lake, then by Franklin and Echemanis Rivers to the height of land at Painted Rock, a short portage over this in to the West Echemanis River, through Hairy Lake and Blackwater Creek into the Nelson River and on into Playgreen Lake on which Norway House was situated. From Norway House it was another three hundred miles across Lake Winnipeg and up the Red River to the Forks. If you can find all these places on the map and then imagine yourself covering the route in a York Boat ... just like the one at Lower Fort Garry ... you will have some idea of the conditions under which the Settlers travelled to reach Red River.

A York Boat

Map showing the grant to Lord Selkirk in 1811, and the route travelled by the early settlers from Hudson Bay to Red River and Fort Daer.

Page revised: 23 May 2011