by Ian Stewart

Winnipeg, Manitoba

The 78th Battalion (Winnipeg Grenadiers) of the Canadian Expeditionary Force was authorized on 10 July 1915 and fought as part of the 12th Brigade, 4th Canadian Division, until disbanded in 1920. Major James Kirkcaldy, who had served in Manitoba militia units before the war and with the 8th Canadian (90th Winnipeg Rifles) during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, was to lead the new Battalion. The Winnipeg Tribune reported that Major Kirkcaldy’s appointment “should stimulate recruiting for he was in the thick of the fighting at Langemarck, St. Julian and Ypres and was invalided home on account of wounds.”

It was announced that the 78th Battalion would not be broken up in England and its men dispersed to different Battalions but would go to the battlefields of Europe as a unit. It reached its 1200-man compliment in only 21 days, setting a new record for recruiting in western Canada, and entrained for Camp Sewell (later renamed Camp Hughes) near Carberry to begin training on 11 August 1915. The camp, as many soldiers complained, was a windy dusty place in the summer. Recruit Roy Armstrong, wrote home that,

it is as they said rather sandy & your eats, your eyes etc. are full. The average man is supposed to eat 1 pound of sand a day. But for all of that it is healthy. I sleep in the sand with 1 blanket underneath & 2 on top, get up at 5:30 & go to bed at 10 after roll call.

Another recruit wrote that “it takes a lot of time washing clean.” Camp Sewell was only suitable for summer training so, in the fall, the troops returned to Winnipeg for the winter.

On 20 May 1916, the 78th Battalion embarked from Halifax on the Empress of Britain and arrived in Liverpool, England on 29 May 1916. Winnipeg lawyer Major Gordon Thornton wrote home that the:

ship used to be a passenger boat but has been pulled to pieces and rough tables made for the men and hooks to hold hammocks put in. They are very crowded but fairly comfortable. All outside light is cut off all the windows & port holes being covered with black paper & nailed shut. The hull has been painted a dull grey like all the British Battle ships so that at a mile it is almost impossible to see them. (Thornton, Canadian Letters)

|

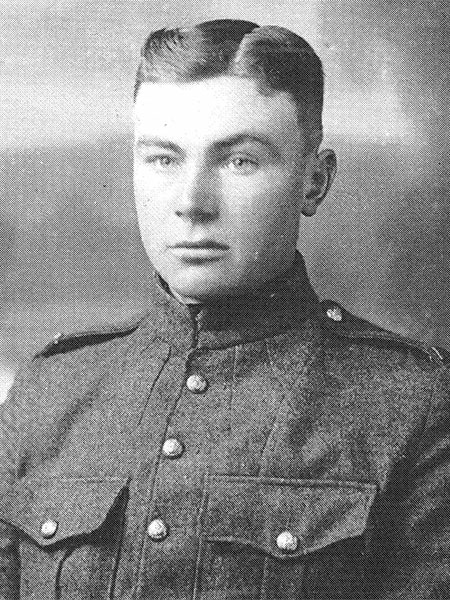

Corporal John Howard Pounds

|

In late August 1916, the Battalion, along with the 4th Canadian Division, went to the battlefields of Belgium and into the trenches of the Ypres salient. The Battalion suffered its first battlefield death on 13 September 1916 when Corporal Jack Pounds of Transcona was killed while working in the trenches; however, as Major Thornton wrote home, “We have been extremely fortunate through it all having had only about four actual deaths and about 10 wounded in the Battalion.”

In October 1916, the 4th Canadian Division was ordered to join the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions fighting in the Somme battlefields in France. On 13 October, during their first foray into the Somme trenches, a work party of 750 men from the Battalion were ordered to assist engineers in trench repairs. Unfortunately, due to miscommunication between the engineers and guides, the work parties became lost in the unfamiliar trenches and took dozens of casualties with eight killed. At the end of October, the battalion took its first tour of the front-line trenches and sent out patrols to obtain information on enemy activities. In mid-November, as the five-months-long bloody Battle of the Somme was coming to its end, the 78th Battalion and other fresh troops from the 4th Division attacked and successfully captured the infamous Regina Trench, where thousands of Canadians had lost their lives in fierce fighting in October. Although the Battalion took heavy casualties, it fared better than other Winnipeg battalions.

The 4th Division joined the other Canadian Divisions on the slopes of Vimy Ridge in November 1916. The Battalion moved into the front line trenches on 29 December 1916 and its normally staid War Diary noted on 31 December 1916:

We ushered in the New Year by putting over a shot in the Hun’s rear area directly opposite our front, sharp on the stroke of 12 midnight.

The Canadian battalions hunkered down in the wet, cold winter mud of Vimy Ridge waiting for the spring and the coming great offensive. They trained and practiced trench raiding to sharpen fighting skills, harass the enemy and gain information. On 19 February 1917, the 78th conducted a major raid on enemy trenches. In a 2 March 1917 letter to Winnipeg, Major Thornton described the raid,

We raided his trenches and blew up a mine, bombed his dugouts and killed quite a bunch of them and while we had a few casualties it showed us what we could do and how much more fun it was fighting than sitting still and taking his guff.

|

Lieutenant James Edward Tait

|

Although the 78th Battalion had been in combat on the Somme, its true “baptism of fire” was during the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Early in the morning of 9 April 1917, the battle began and 800 men from the 78th Battalion leapt out of their trenches to attack Hill 145, the Ridge’s highest point. However, the supporting battalions failed in their assigned tasks and the Winnipegers came under heavy machine gun fire from both flanks and from counter-attacking enemy troops. “We had the ”pimple” of the ridge to take,” wrote Sergeant Chris Collis, who was buried alive during the battle and later declared unfit for further service,

when we went over the top it was like a ploughed field. The mud was really hell, but we plugged on and on. I saw several of our officers fall and as they fell they urged their men to still go forward. A braver bunch never went into battle.

One of the officers was Lieutenant James Tait who won a Military Cross for “Conspicuous Gallantry”. His citation reads:

Early in an assault he was wounded, and all the other officers killed or wounded, but he led his company with great fearlessness and determination through intense fire to the objective, and although unable to walk, supervised its consolidation, finally crawling back alone to leave for others the four (stretcher) bearers.

Normally about 15% of a battalion’s strength is left out of battle to preserve the unit’s integrity in case of catastrophic loss. However, according to the War Diary, by the end of the day Lieutenant-Colonel Kirkcaldy had ordered the entire Battalion to the front line. All but one of its officers were killed or wounded (only six of the Battalion’s original officers survived the war) and although it had taken the objective, it suffered 600 casualties.

|

Private Robert Richardson

|

In the course of the battle, three men from Basswood, Robert Richardson, Daniel Matheson and Tom Cassady were killed. The story of their enlistments and deaths are dramatically retold by George Hambley in his local history, The Golden Thread or The Last of the Pioneers: A Story of Basswood and Minnedosa, Manitoba. The bodies of the “Basswood Buddies” were never recovered and they are memorialized on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. Even though having suffered such heavy losses, the 78th returned to the front line trenches in the final week of April.

Through the summer of 1917, the 78th Battalion maintained trenches in the Canadian front lines and was not ordered to participate in the August Battle of Hill 70. In October 1917, the Battalion, along with the other battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, returned to the Ypres salient to fight in the Battle of Passchendaele.

The Battalion took up its battle positions on the night of 28 October and remained in the front lines until 3 November. It took all its objectives and was the first Canadian battalion to enter Passchendaele village. The 78th took 400 casualties, many of which the War Diary reported came from a gas attack on the night of 28 October. In the course of the battle, Lieutenant-Colonel Kirkcaldy was seriously wounded by an enemy sniper while he was on patrol in the front lines. In a 3 November 1917 letter home, Private Henry Trudel of Mariapolis, wrote of an ordinary soldier’s experience in the horrible battle:

Dear Parents,

I believe that you have learned that I was wounded by a blast of shell fire, on my left knee and also to my head. … These are not serious injuries … we marched 3 miles to get to the Red Cross under a storm of shells. … Here, it rains every day. We are in the mud up to our butt … The cold in Canada is better than the weather here … Will this terrible nightmare ever end? From your son who thinks of you always in his prayers. Kisses to the whole family, Henry

Henry Trudel, Local World War 1 Stories, Manitoba Historical Society

The Canadian divisions rested and took on replacements in the winter and spring of 1918. However, they were given weeks of training in open warfare techniques which would serve them well in the summer of 1918. The next great series of battles the Canadian divisions’ faced were the Last 100 Days battles which raged from 8 August to 11 November 1918 and the 78th Battalion played their part in Canada’s greatest victories.

The first of the battles took place at Amiens, France, between 8-12 August 1918. The 78th entered the battle on 8 August and fought till relieved on 11 August. During its advance, the 78th’s advance was stalled by heavy enemy machine gun fire and artillery bombardment. While under this heavy machine gun fire, Lieutenant Edward (nicknamed Madman) Tate, who had won a Military Cross during the battle of Vimy Ridge, won the Battalion’s first Victoria Cross. Tait single-handedly knocked out an enemy machine gun post and inspired his men to advance on the enemy. His Victoria Cross citation reads: He “displayed outstanding courage and leadership and although he was wounded he continued to direct his men until he died on August 11th 1918.” The Battalion suffered 350 casualties.

Over 20,000 Canadian soldiers killed in the First World War have no known grave. They are memorialized on the Canadian Vimy National Memorial, if killed in France, or the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ieper (Ypres), Belgium, if killed in the Ypres salient. During the Battle of Amiens, the 78th Battalion had 46 fatalities with 35 missing. In 2005-2006, eight of the 78th Battalion missing were discovered and five identified through DNA analysis: Lieutenant Clifford Neeland, Private Sidney Halliday, Lance-Sergeant John Lindell, Private Lachlan Peters, and Private William Simms. In 2015, the eight were buried with full military honours at the Caix Military Cemetery in Caix, France. (Discovery at Hallu, National Defence & Canadian Forces)

|

Lieutenant Samuel Lewis Honey

|

In September, the Battalion took on replacements and trained for the next battle. In its last major battle of the war, the 78th moved up to its position near Bourlon Wood during the Battle of the Canal du Nord (27 September to 11 October). On 29 September, when the Battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and with most officers wounded, Lieutenant Samuel Lewis Honey DCM,MM led his men in clearing enemy strong points which, as his Victoria Cross citation stated, led to the capture of Bourlon Wood. Honey died of wounds received during the battle and was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

In the final month of the war, the Battalion continued sending out patrols but saw little action. The War Diary noted on 19 October 1918 that when the Battalion left its billets in Auberchicourt, France:

The liberated civilians lined the streets and welcomed us. They said never were they more happy and their smiling countenances confirmed that. White flags were waving on windmills and church towers, which the civilians had pasted up, signifying that the Hun was out of the town. The French flag was hanging from most of the windows, bouquets of flowers were handed to the Major, also to the Adjutant riding at the head of the column, and also to some of the Company Commanders. One old lady, who lived in the Chateau, rushed out and stopped Major Semmens riding in front and asked piteously if he would bring back her son whom the Germans took with them the previous day.

On 5-6 November, the 78th faced the enemy for the final time. Advancing behind a rolling barrage it captured almost 100 prisoners, 20 machine guns and moved into Belgian territory for the 11 November Armistice. The Battalion’s men were kept busy with training and sports for the next months. On 28 April 1919, the 78th entrained for Le Havre and were notified that they would leave France and sail to England on 3 May. On 9 June 1919, 26 officers and 591 men returned to Canada on the steamship Adriatic and arrived at Winnipeg’s Union Station on 12 June.

Library and Archives Canada: Canadian Virtual War Memorial, Personnel Records of the First World War, War Diaries of the 78th Canadian Infantry Battalion.

Canadian War Museum Archives

Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum & Archives

University of Manitoba Digital Collections

Kenora Great War Project, www.kenoragreatwarproject.ca

Canadian Great War Project, www.canadiangreatwarproject.com

Canadian Letters, www.canadianletters.ca

Manitoba Historical Society, www.mhs.mb.ca

War Amps, www.waramps.ca/about-us/our-war-amputee-members/curley-christian/

Winnipeg Free Press

Winnipeg Tribune

Jim Blanchard, Winnipeg’s Great War: A City Comes of Age, University of Manitoba Press, 2010.

Gerald Gliddon, For Valour: Canadians and the Victoria Cross in the Great War, Dundurn, 2015.

George Hambley, The Golden Thread or The Last of the Pioneers: A Story of Basswood and Minnedosa, Manitoba, 1971

78th Overseas Battalion Winnipeg Grenadiers, 1916

This page was prepared by Ian Stewart and Gordon Goldsborough.

Page revised: 11 November 2021