by Scott Stephen

Parks Canada, Winnipeg

|

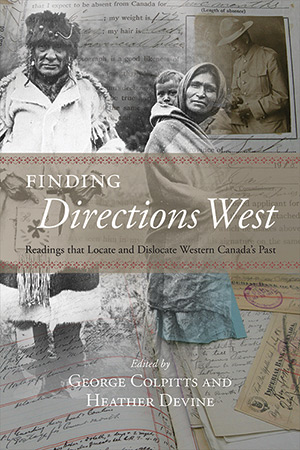

George Colpitts and Heather Devine (eds.), Finding Directions West: Readings that Locate and Dislocate Western Canada’s Past. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2017, 330 pages. ISBN 978-1-55238-880-8, $34.95 (paperback)

This is the most miscellaneous contribution to an already fairly miscellaneous series from the University of Calgary Press. “The West” series “explores our sense of place in the West. How do we define ourselves as Westerners and what impact do we have on the world around us?”[1] Unlike the other volumes in this excellent series, this is a collection of conference papers, selected from the 3rd Biennial Conference on Western Canadian Studies, held at the University of Calgary in June 2012.

This is the most miscellaneous contribution to an already fairly miscellaneous series from the University of Calgary Press. “The West” series “explores our sense of place in the West. How do we define ourselves as Westerners and what impact do we have on the world around us?”[1] Unlike the other volumes in this excellent series, this is a collection of conference papers, selected from the 3rd Biennial Conference on Western Canadian Studies, held at the University of Calgary in June 2012.

The ‘potluck’ nature of most academic conferences is evident in this collection, but that is only a problem for the editors. Colpitts and Devine spend fourteen pages in their introduction trying to tie the articles together into something like a coherent whole, without ever really succeeding. Indeed, the value of the individual essays lies in their individuality, and many different sorts of readers will each find something in them to delight, provoke, and amuse.

Issues of preservation and presentation are front and centre in the opening three essays. Kimberly Mair analyses Indigenous-related galleries at the Royal BC Museum and the Royal Alberta Museum. Recognising the need to de-colonise our museum spaces is nothing new, but her discussion of how curatorial practice continues to privilege Euro-Canadian points of view even when focusing on Indigenous historical experiences illustrates how much work remains to be done. Mair also sees a lingering preference for documentary forms of retaining and transmitting knowledge—no matter how problematic the documents may be—and Heather Devine tackles this in her account of Métis vernacular historian J. Z. LaRocque. But dominant biases towards (and within) documentary recordkeeping contribute to power imbalances besides those between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. Cheryl Avery and Shelley Sweeney compare and contrast the extent to which LGBTQ+ experiences are present—or, more commonly, absent—in Canada’s publicly-funded archives.

If these essays raise the thorny question of where do we find ourselves in museums, archives, and history books, those which follow remind us that finding ourselves can be complicated by the shifting and contested terrain of who ‘we’ are. Will Pratt’s reassessment of Methodist missionary Rev. John McDougall demonstrates that even the most self-confident of imperial agents can find their worldviews reshaped by lived experiences among other peoples and other places. Of course, some aspects of identity can feel more important than others, and some barriers between ‘us’ and ‘them’ serve to reinforce and to expand how we define who ‘we’ are and what ‘we’ are capable of. This can be seen in Mallory Richard ’s examination of how prairie suffrage movements in the early 20th century championed Anglo-Canadian women’s past and future contributions to society at the expense of European immigrants and non-white Canadians; and in Sarah Carter’s overview of Emmeline Pankhurst, Emily Murphy, and their promotion of Anglo-Canadian ‘race betterment’ in the 1920s.

While some barriers are consciously constructed, others arise from less visible foundations. Sterling Evans offers us the travel diary of Mary Beatrice Rundle, who toured Alberta in the summer and autumn of 1935 as secretary to the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry in that province. Her observations were rich and detailed, yet omitted or overlooked much of the economic and social damage wreaked by the depression years on both rural and urban prairie communities. Rundle was a newcomer to the West: her father had been an admiral in the Royal Navy, but this was her first trip across the Atlantic. The eyewitness account which her diary bequeaths to us is very much that of the educated metropolitan travelling on government business, and the perspectives which such a viewpoint both encourages and discourages harken back to Mair’s discussion of privileged perspectives still prevalent in museum practices. Shifting our perspectives can have significant real-world results, as Max Foran finds that the Anderson Grazing Rates Report of 1941 significantly altered how western ranchers thought about and interacted with the landscape within which they lived and worked.

‘The landscape,’ of course, is one of those often-used singular nouns, which conceals a multitude of pluralities. The Anderson Report reinforced a new perception (emerging in the difficult decade of the 1920s) of rangelands as much more vulnerable than the first two generations of western Canadian ranchers had realised, while the Royal Commission of which Rundle was a part was prompted by the challenges faced by a once robust but now fragile Alberta coal industry. These are questions about how we inhabit spaces we already occupy—in these cases spaces of production, distribution, and marketing, but the Royal Commission also addressed such spaces as workplaces. Rev. McDougall, Emily Pankhurst, and Emily Murphy were each in their own ways seeking to occupy new spaces and to redefine them: for the missionary, spiritual spaces, and for the reformers, political spaces, but each with social and economic ramifications. And, of course, it is not merely enough to occupy a space, but to remember and commemorate one’s occupation of that space through museums, archives, books, and stories.

If it seems a stretch to present the ranching and coal industries, the expanding frontiers of Christianity, and the reformulation of gender and ethnic imbalances in the political realm equally as ‘spaces,’ then this collection’s final essay comes to my aid with the knick-of-time promptitude of my favourite fictional Mountie, Sergeant Preston of the Yukon (who was, of course, himself seeking to reshape the spaces in which he worked). In tracing the conception and construction of the Banff School of Fine Arts, PearlAnn Reichwein and Karen Wall draw on Henri Lefebvre’s ideas about space as a social and cultural production. That is to say, we use spaces to express and exert particular meanings and particular relationships, as when we build a modernist campus in an urbanised landscape within Canada’s first and most iconic national park. From the hushed reverence of the public archives to the electrifying political meeting, from the ‘frontier’ missionary meeting with potential converts to the Royal Commission meeting with mineowners and mine-workers, and from the first essay in this insightful miscellany to the last, we gain perspective on how ‘we’ define ourselves not just using adjectives but by occupying, defining, expanding, and defending ‘our’ spaces.

1. University of Calgary Press website, “Series,” https://press.ucalgary.ca/series#the-west, accessed 25 May 2019.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 4 June 2021