by Meg Stanley

Calgary, Alberta

|

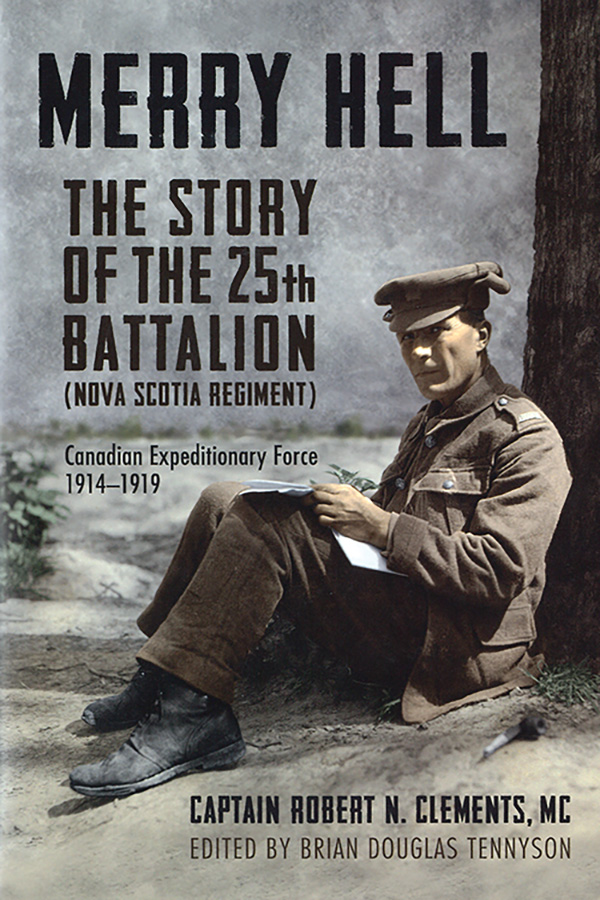

Captain Robert N. Clements, MC, Merry Hell: The Story of the 25th Battalion(Nova Scotia Regiment), Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1919. Brian Douglas Tennyson (ed.), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013, 296 pages. ISBN 978-1-4426-4496-0, $45.95 (cloth)

Formed in the winter of 1914–1915, the Nova Scotia’s 25th Battalion trained first in Canada and then in England before embarking for France in September 1915. The battalion remained in Europe, serving in the occupation of Germany, until finally returning home to Halifax in May 1919. The author of Merry Hell, Robert N. Clements, enlisted as a private with the 25th in November 1914; he returned to Halifax with the battalion in 1919 as a Captain having seen action in a long list of well-known Canadian battles on the western front. From a middle-class background, Clements was working as a bank clerk in Yarmouth before he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) at the age of twenty. After the war ended, Clements resumed his career in commerce working in management in various businesses connected to textile manufacturing. He died in Halifax in 1983.

Formed in the winter of 1914–1915, the Nova Scotia’s 25th Battalion trained first in Canada and then in England before embarking for France in September 1915. The battalion remained in Europe, serving in the occupation of Germany, until finally returning home to Halifax in May 1919. The author of Merry Hell, Robert N. Clements, enlisted as a private with the 25th in November 1914; he returned to Halifax with the battalion in 1919 as a Captain having seen action in a long list of well-known Canadian battles on the western front. From a middle-class background, Clements was working as a bank clerk in Yarmouth before he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) at the age of twenty. After the war ended, Clements resumed his career in commerce working in management in various businesses connected to textile manufacturing. He died in Halifax in 1983.

The story of how Clements’ story came to be written and published is a story within the story. Clements explains his project, which he undertook in the 1970s, in terms of both the present and the past. Of the present he wrote “today, with so much dissension and unrest in our wonderful country we must never forget the honour and pride they [the men of the 25th] felt in facing the world with the word ‘Canada’ on their shoulders” (p. 7). As for the past, he wrote that “Merry Hell has been written solely on behalf of the men in ranks who with their officers served in infantry battalions of the CEF 1914–1919. For the first time it tells their full story in their own words” (p. 3).

Whether Clements sought to have his manuscript published is not clear, but he did send copies to Library and Archives Canada and to the Nova Scotia Archives. Clements died in 1983 and Brian Tennyson, who edited the manuscript, first encountered it at the Nova Scotia Archives when he was editing for publication a collection of wartime letters written by Percy Wilmot, a Cape Bretoner who, like Clements, served in the 25th Battalion.

In Merry Hell, Clements blends social and battalion history with memoir. Although the narrative is written in the third person, it often seems that Clements is writing about his own direct experience. This has the curious effect of turning the protagonist into an observer. Clements’ introduction does not provide much detail about his writing process, and the reader is therefore left wondering where the memoir ends and the narrative history starts; the boundaries are not clear. We know he did do research—consulting published and archival sources and former comrades, but the full scope of that research and how it was used is not evident, as there are no footnotes. The titles for the chapters on Vimy, “The Corps Comes of Age,” and the Somme, “Why???,” suggest that his memories were influenced by subsequent historians’ interpretations of these events, but it is left to the reader to puzzle over how Clements’ memory and subsequent historical work intersect in the text. It is also not clear whether Clements kept a journal or diary. The descriptions he provides about day-to-day life suggests that he must have done so—as it seems unlikely one could recall the kind of detail he furnishes—but he does not mention it. This is unfortunate, as without this information the reader is left unsure of how the narrative has been constructed.

Although the provenance of the details is unclear, I found Clements’ descriptions of the minutiae of day-to-day life in the CEF the highlight of the book. The extended descriptions of bathing routines, killing lice, ragged and mud-encrusted soldiers, or the antics of the Robert the Bruce (the goat that served as the unit’s mascot) distinguish this work from other battalion histories. Here are stories from a man, who rose through the ranks and was promoted in the field; who learned how to survive in hell. He is neither a revisionist nor a hagiographer (although sometimes he does lean in that direction); rather, he is the man in the middle and he writes as one. Think of this as history from the perspective of the educated man who began work as a clerk and rose into middle management without forgetting the lessons he learned as a clerk. He is loyal both to the cause and to his comrades, but he is not uncritical. That being said, Clements is definitely a man of his times and class —he writes about drinking, but respectability constrains him from writing much about sex; and his criticisms are carefully aimed at individual problems, not at the whole. Of Courcellette, where the 25th suffered tremendous losses, he writes: “call it glory if you like. Some of those who were there and managed to survive had other words for it and for those higher up who had sent them and their wonderful young friends head-on into that deadly trap” (p. 153). And the story of a riot between Canadians and Anzacs that ran over 24 hours and was broken up by the English cavalry is one that illustrates the fragility of discipline and order. It is certainly true that Clements tells humorous stories (note the goat above), but he also tells difficult ones—of men decapitated, gassed, and directly hit. As he points out in explaining the book’s title, the men needed “all the humour and relaxation they could find to control the tensions and endure the hells they had to face and overcome” (p. 7).

Desmond Morton (in When Your Number’s Up) and other historians cover elements of this social history of the CEF in well-written syntheses based in a wide range of sources. Clements’ on the other hand provides a singular voice that adds valuable additional texture and individual nuance. As he notes in the preface, “No two people ever had exactly the same experience” (p. 3). In general, the first half of the book is stronger than the second, where the narrative of engagements and troop movements begins to overwhelm the other elements of the story. This may simply be a function of how the war unfolded for Clements and the 25th Battalion in 1917 and 1918; and perhaps, how ordinary hell had become for him. It was, as he writes, a case of one “dirty job” after another (p. 179).

One of the very interesting threads in the story is that of the “thinker’s group,” of which it seems Clements was an active participant. Here we see the operation of an informal sub-group within the battalion, and how military law and leadership were subverted by the group at various points—to steal potatoes from a farmer to supplement their diet, to prevent the execution of a raid that the group judged as unnecessarily risky to the lives of ‘their’ men, and to steal Lee Enfields from the English to replace their inadequate Ross rifles. These stories are told in a chummy tone, and yet the acts themselves are undertaken by men who clearly understood that their survival, and that of those who depended on them, required subversive action.

Brian Tennyson’s introduction and list of additional reading add important context and information. He includes a good but not overly detailed summary of the relevant historiography. He also describes Clements’ background and life subsequent to 25th Battalion. Unfortunately, he does not list his sources for this work, and while it is unclear what materials he consulted, it seems he must have reviewed Clements’ service record. He does mention a hospitalization in 1916 noted in the record, but not another in 1917 that took Clements out of the action for 132 days. As noted above, Clements seems less engaged in the story by 1917, and this absence may go some way to explaining that. A nominal list of the original officers, non-commissioned officers, and ranks of the 25th Battalion rounds out the book. An index is provided.

This is a unique and highly readable addition to writing about the Canadian Expeditionary Force. I would recommend it to anyone interested in the subject as a supplement to more systematic and synthetic histories. It is unfortunate that Clements did not live to see his work published.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 17 November 2020