by Margaret Bertulli

Winnipeg, Manitoba

|

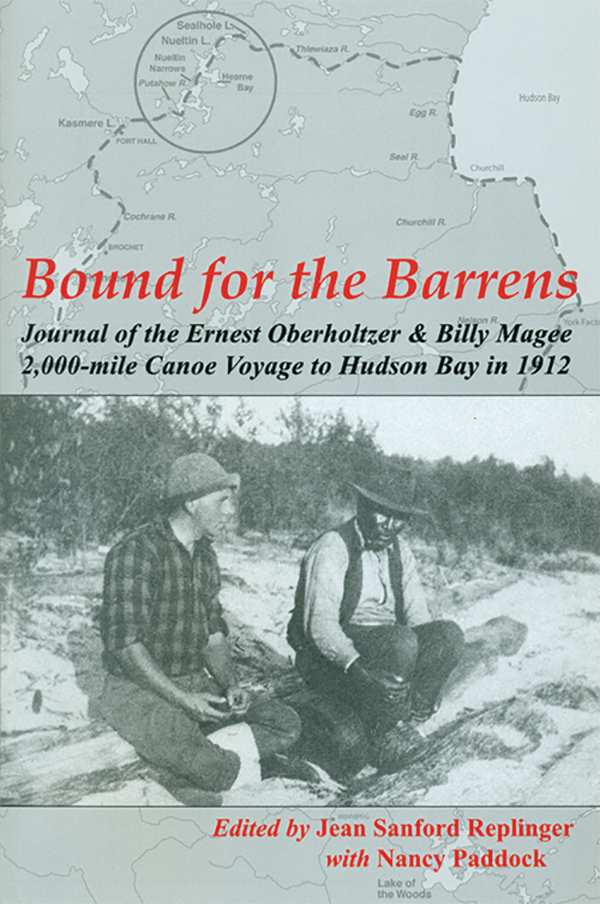

Ernest Oberholtzer, Bound for the Barrens: Journal of the Ernest Oberholtzer and Billy Magee 2,000-mile Canoe Voyage to Hudson Bay in 1912. Edited by Jean Sanford Replinger with Nancy Paddock, Marshall, Minnesota: Mallard Island Books, 2012, 248 pages. ISBN 978-0-9849052-0-1, $19.95 (paperback)

As the title of this book indicates, in the early 1900s American traveller and author, Ernest Oberholtzer, and Anishinaabe traveller, Billy Magee, undertook a journey of some two thousand miles: from central Manitoba, north to Nueltin Lake, east on the Thlewiaza River to Hudson Bay, south along the coast to Churchill and York Factory, and then southwest along Hayes River to Gimli on Lake Winni-peg. This was a remarkable journey for any time. Not only was it accomplished in one season (133 days), but it was done at a time when sections of this route were largely unmapped and had not been travelled by Euro-North Americans since the expedition of English explorer Samuel Hearne and Chipewyan leader. Matonabee from Churchill across the Barren Grounds to the Coppermine River in 1770–1772, and later by surveyor J. B. Tyrrell of the Geological Survey of Canada in 1893 and 1894.

As the title of this book indicates, in the early 1900s American traveller and author, Ernest Oberholtzer, and Anishinaabe traveller, Billy Magee, undertook a journey of some two thousand miles: from central Manitoba, north to Nueltin Lake, east on the Thlewiaza River to Hudson Bay, south along the coast to Churchill and York Factory, and then southwest along Hayes River to Gimli on Lake Winni-peg. This was a remarkable journey for any time. Not only was it accomplished in one season (133 days), but it was done at a time when sections of this route were largely unmapped and had not been travelled by Euro-North Americans since the expedition of English explorer Samuel Hearne and Chipewyan leader. Matonabee from Churchill across the Barren Grounds to the Coppermine River in 1770–1772, and later by surveyor J. B. Tyrrell of the Geological Survey of Canada in 1893 and 1894.

But the title does not tell the whole story, of course. The book has three parts: a prologue, the journal with photos, and an afterword. The former deals with utilitarian matters of the book’s production, but does not provide a comprehensive overview of the journey, its inception and aftermath—an omission at a point that I found to be unfortunate, as the journal itself does not make thrilling reading.

The journal outlines quotidian activities and understates the inherent complexities and struggles of exploratory travel; however, readers familiar with the North’s challenges will readily realize the magnitude of the canoeists’ accomplishment. Oberholtzer’s prosaic recounting minimizes the resolve and gruelling exertions required to paddle/sail and portage a canoe and all supplies in unknown territories, extreme conditions, and without a guide. Given the difficulties of the journey and the energies expended in daily navigation, it is noteworthy that Oberholtzer left such a good daily written and photographic record.

The final section of the book was, to me, the most interesting. In addition to ancillary documents, the afterword contains a synthesis by Robert Cockburn, which explains the significance of the events dispassionately described by Oberholtzer.

The twenty-eight-year-old Oberholtzer prepared for his trip by voraciously studying travel accounts of the Barrens. He engaged the services of Billy Magee, without whom he would not have embarked on this journey. Fifty-one-year-old Magee had previously been Oberholtzer’s canoeing companion in the Rainy River district. The present journey was undertaken in an eighteen-foot Chestnut “Guide Special,” made by the Chestnut Canoe Company of Fredericton, New Brunswick. It is sobering to think that the loss of the canoe or supplies in rapids could have resulted in a very different outcome. Oberholtzer’s decision on 8 August 1912 to substitute the original intention of following Tyrrell’s route to the Kazan River with a trip down the Thlewiaza to Churchill was critical in their survival and success. A demanding part of the journey was finding the exit from Nueltin Lake to Thlewiaza River without a map and without a current to follow. At another crucial point 120 miles from Churchill, they were greatly helped by an Inuit family headed by Uturuuq (Bite) and Tassiuq; without this timely assistance it is doubtful whether Oberholtzer and Magee could have succeeded. A copy of Oberholtzer’s map of this largely unexplored territory (at a scale of three miles to the inch and accurate given the circumstances of its compilation) was sent to the Chief Cartographer in Ottawa, who did not seem to recognize the scale of the accomplishment and the importance of this information.

The utility of Bound for the Barrens lies in making the journal and excellent photographs accessible as a primary reference, as Oberholtzer did not publish any of these materials, despite his best intentions.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 29 March 2020