by James B. Waldram

Department of Native Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Manitoba History, Number 15, Spring 1988

|

In 1875, the first of the northern Indians in what is today Manitoba signed a treaty surrendering their lands to The Queen of Canada. By 1910, all of the land had been surrendered, and the Indians provided with small tracts of reserve lands in their once expansive territories. In 1962, the Indians of the Chemawawin Indian Band, living today at Easterville, were again contacted by government and asked to surrender their remaining lands. And in 1969, the Indian people of South Indian Lake were likewise asked by government to move aside.

The government requests of the 1960s were not stimulated by a need for Indian land for agricultural purposes, nor by a desire to acquire minerals or to navigate rivers. In the 1960s a new era was dawning in northern Manitoba, one which would replicate the treaty process and once again leave the Indian people without the benefits that should have accrued from their status as original occupiers of the land. This was the era of the hydroelectric project, and it necessitated a whole new round of negotiations and agreements between the government and the Indian people.

The purpose of this article is to examine briefly the legacy of hydro development in the north by focussing on two key questions which have parallels in the current debate on the treaty-making process: what were the Native people of northern Manitoba promised in return for hydro development in their territory, and what did they receive. [2] It is my argument that the Manitoba government has been satisfied to facilitate the “modernization” of Native communities, in effect providing an image of “development” through extensive infrastructural improvement. However it has been unable, or unwilling, to convert the energy, employment, and income potential of hydro development into programs to enhance the economic situation of the Natives [3] of the region. In effect, the promise of “development,” presented to the northern Native people, has been little more than an old treaty promise, uttered when necessary to secure compliance, and forgotten almost immediately thereafter.

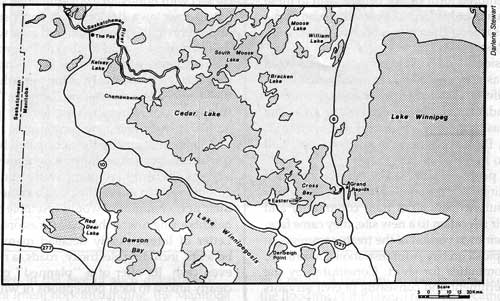

The people of Chemawawin, now Easterville, first heard of the plans for a dam at Grand Rapids in the spring of 1960, even though actual planning of the project had been underway since at least 1957. Chemawawin at the time was a small, semi-isolated community of some 350 people. Located at the confluence of the Saskatchewan River and Cedar Lake, the people of the community supported themselves through hunting, fishing, trapping, and occasional wage labour in a small sawmill. There were no roads to the community, and no electricity for the Band members. Log houses and tar-paper shacks provided shelter from the bitter Manitoba winters. Cedar Lake and the Saskatchewan River provided the only transportation routes to towns such as The Pas and Grand Rapids. People only occasionally ventured forth from Chemawawin to these places, and usually only for quick visits to execute some economic transaction. Then it was back to the security of the “Old Post.”

To an outsider, Chemawawin might have looked poor. But it was not. The people enjoyed a rich social and cultural life, and obtained the necessary income from the abundant natural resources of the area. The community was located in a beautiful site, with thick ground cover. Poverty, being a relative concept, had no meaning to these people.

When the people of Chemawawin were informed of the impending Grand Rapids dam, a project which would flood out virtually all of their community and necessitate their relocation to a new site, they came face-to-face with their own version of the treaty commission: The Grand Rapids Forebay Administration Committee, or Forebay Committee for short. Constituted by the Manitoba government and consisting of civil servants whose numbers varied over the years, the Forebay Committee was charged with the responsibility of negotiating with the Indians for the surrender of the reserve land at Chemawawin, and for selecting new reserve land elsewhere in the region. The Forebay Committee proved to be an amorphous body, with the power to negotiate but not to act, and was given a mandate to modernize as well as relocate the Indian and Métis residents of Chemawawin. But, like “poverty,” “modernization” too is a relative concept.

The substance of what the Chemawawin people would be offered in return for the surrender of their reserve lands was communicated in a letter to the Chief in April of 1962. This letter, known alternately as the “Letter of Intent” or “Forebay Agreement,” [4] was, in effect, a 1960s version of Treaty No. Five, which the Chemawawin people had signed in 1876. Indeed, the parallels between the Letter of Intent and Treaty No. Five were not lost on the people, nor were its implications. They wrote to the Manitoba government:

We feel that this letter is similar to a Treaty. We cannot accept what we do not think is right, as it is not we who will suffer for our mistake, but our children and our children’s children. [5]

But opposition to the dam was fruitless. The Manitoba government was committed to the project, and the people were warned that “the job is going to be built” [6] regardless of their decision to negotiate a compensation deal. Significantly, no lawyer was made available to the community to assist it in its deliberations. The Native people themselves likely did not know of the existence of lawyers as professional advocates, and there is no indication that they ever requested one. [7] The Manitoba government felt that it could represent the interests of these people adequately through its Forebay Committee. The Chemawawin residents, who spoke little English and who had had little extensive contact with non-Native governmental structures, were left to their own devices. Not surprisingly, the little opposition to the project that did exist soon dissipated. “Government” could not be challenged, and the people reluctantly accepted their fate. Similar to the way they reacted to the treaty of the past, the people eventually agreed to a package of “benefits,” this time from the provincial rather than the federal government, to go along with their new community.

Paramount among the anticipated benefits was the construction of a new, fully modern town, with named streets, electricity, running water, bus service, and automobiles. In effect, the people came to believe that their new community would resemble the prosperous neighbouring towns they had occasionally visited. The Letter of Intent clearly detailed many of these new benefits, including electricity, roads, a new school, and even cash. Its offer of a “planned” community was clearly linked to local perceptions of what was actually offered, and as with the treaties there are still arguments today over the extent to which oral but unrecorded promises were made to the people in attempts to get them to relocate. There are also disputes over the selection of the Easterville site itself, with the Manitoba government insisting that the people democratically selected the site from a short list of alternatives, and the people insisting that the Easterville site was the only one that was really offered to them as a location in which all of the promised services and facilities could actually be delivered.

While the vision of a new town rising phoenix-like from the hydro flood was the most tangible component of the Letter of Intent, almost forgotten was the clause committing the Forebay Committee and the Manitoba government to undertake “every step possible to maintain the income of the people of Chemawawin at the new site.” [8] And in 1965, when the first winters’ snows melted around the new Chemawawin community of Easterville making painfully visible the lack of soil and vegetation, and as the waters rising behind the Grand Rapids dam changed forever the face of the lake they knew so well, obliterating not only the shoreline but also the habitat for moose, muskrat and fish, the importance of this clause became evident. How would the economy and the lifestyle of the Chemawawin people be maintained in the face of such devastation?

The Letter of Intent notwithstanding, the Manitoba government proved reluctant or incapable, or both, of maintaining the people in their new site. Designed according to a southern urban model, the community was characterized by new houses lining named gravel streets. The hub of the new community, located more or less at its physical centre, consisted of a new school, recreation hall, council office, co-op store and nursing station. The new community certainly looked modern, prompting Manitoba Hydro to actually describe it as similar to “a lakeside summer resort.” [9] The Manitoba government implicitly believed that infrastructural modernization was tantamount to “development.”

Easterville, 1979.

Source: James B. Waldram

But the site itself soon presented a different face to its new inhabitants. There was little actual ground cover or soil, and the location was dominated by gravel and rock outcrops that contrasted sharply with the natural beauty of the Chemawawin site. And the new site soon proved hazardous to health: the thick lime-stone prevented the establishment of pit toilets, and sanitation became a problem. The quality of the well water then became contaminated with human wastes. Floating debris began to disrupt the activities of commercial fishermen, who had difficulty locating moving fish populations in the years immediately following the flooding of the lake. Beginning in 1971, the commercial fishery was closed by the provincial government as a result of mercury contamination likely caused by the flooding of the lake. Trapping became increasingly unproductive, as the rising waters behind the dam flooded out beaver and muskrat habitat. Eventually most people gave up trapping altogether. Similarly, it became more difficult to hunt moose along the flooded shorelines of Cedar Lake. Social assistance payments increased accordingly. The promised road access to other communities, particularly Grand Rapids and The Pas, proved to be a mixed blessing, for while the people could travel to these centres to shop and for recreation, access to alcohol greatly increased, and social problems related to alcohol abuse and unemployment soon became prevalent in Easterville.

The spirit of the people of Chemawawin seemed to break once they were in Easterville. To paraphrase Robert Chambers, it seems as though once government has interfered extensively in a people’s lives, they are never quite the same again. [10] Alcohol abuse became a problem as the economy withered, and government programs seemed incapable of stopping the destructive spiral. Granted, the new community looked modern, with its streetlights, gravel roads, new school, hall, and houses. But the image that infrastructural development gives is a misleading one. The promise of the Letter of Intent, fulfilled to a degree that is still a matter of debate, proved to be of little real value to the people. The extent to which the people of Chemawawin have recovered from the twin blows of relocation and hydro flooding is due, in large measure, to their own initiative and resilience.

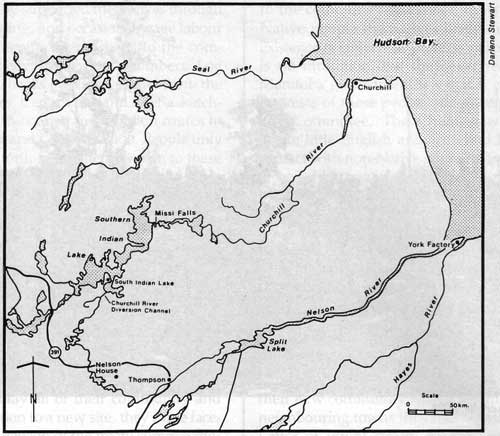

In the 1960s, the people of South Indian Lake were even more remote than those of Chemawawin, but this situation did not last for long. No sooner was the Grand Rapids dam completed than an announcement was made that the government wished now to turn its attention to the powerful Churchill and Nelson Rivers. The little community of South Indian Lake, isolated along the shores of Southern Indian Lake without roads or electricity, was in the way of “progress” just like Chemawawin had been. And just like the people of Chemawawin, the people of South Indian Lake were asked to relocate and reestablish themselves in the post-flood environment.

The community of South Indian Lake strenuously fought the hydro project, and through a number of public hearings in 1969 it became evident that many southern Manitobans were also against it. But all the protests fell on deaf ears, and even though the hydro controversy contributed in part to an election loss for the Conservative party and victory for Ed Schreyer’s NDP, little changed as a result. From its early design phases, the diversion project was a fait accompli, and as for the Indians of South Indian Lake, the only question was how to get them to accept a compensation package and relocation. Although the majority of the residents of South Indian Lake were treaty Indians, theirs was not a reserve community. [11] The provincial government did not require the legal surrender of any land by the Indians, and the federal government was unwilling to come to the defense of the beleaguered community. Hence, the community’s position in the ensuing negotiations was very weak.

When the NDP had been elected in 1969, Edward Schreyer had rhetorically asked,

Can we ... face up to the prospect of disrupting two communities of 700 people, completely upsetting the lake on which they depend for their livelihood making it quite impossible for at least some of them to continue to live independently? [12]

The answer, apparently, was “yes,” but tempered with an apparently sincere desire to reduce the impact as much as possible, and to provide adequate compensation to the South Indian Lake people. However, this sincerity was of little consequence to the people, since the Manitoba government quickly terminated the funds it had available to the community for legal representation. The wishes of the local flood committee were ignored as Hydro officials began to approach individual residents with compensation deals. As the diversion project was completed, individuals who initially opposed the project began to sign away their claims, succumbing to the old “divide and conquer” strategy now implemented by Manitoba Hydro. Realizing that the war was now over, Premier Schreyer wrote to the South Indian Lake people. Acknowledging that “some negative effects” were likely as a result of the diversion project, he outlined the “benefits” that had been created:

1. “direct color TV broadcasts of improved quality”;

2. direct dial telephone service;

3. unlimited electrical power, enabling the use of “many electrical appliances, such as stoves, refrigerators, and TV’s”;

4. some job opportunities on clearing and construction work [13]

Furthermore, Schreyer stated that, “The Government has already indicated that it is committed to doing everything possible to ensure that people in Northern Manitoba have at least comparable options available to them after the diversion program as they had before.” [14]

Post-impoundment shoreline along Southern Indian Lake, 1982.

Source: James B. Waldram

The new town of South Indian Lake was indeed “modernized” in a fashion similar to Easterville. The people were consolidated on one shore of the lake, and new homes were provided by Manitoba Hydro and the government. Electricity was eventually provided as well, including electric heat for the homes. A new town centre complex was constructed, including a store, school, and nursing station. A recreation hall was also provided. A gravel road was constructed to link all the new residential areas together. Monetary compensation was provided in the areas of trapping and commercial fishing. Today, ferry service and a road provide residents with easy access to the nearby towns of Leaf Rapids and Lynn Lake. Indeed, it would appear that the community has greatly benefitted from the hydro project.

The image of development engendered by the new structures and services shrouds the reality of a community negatively affected by hydro construction. Compensation notwithstanding, the local economy has gone into a tailspin as a result of the flooding of Southern Indian Lake. The commercial fishing on the lake has been most seriously damaged, with not only declining catches but also declining quality. Southern Indian Lake was once an “export” or top quality whitefish lake, but since the diversion project the quality has steadily deteriorated to the point where, today, the whole lake has been downgraded to “continental” or “cutters.” Mercury contamination in the lake, likely the result of the flooding, has periodically resulted in the closure of northern pike commercial fishing. The trapping industry has not fared much better. A number of traplines around the lake were damaged by rising waters, and transportation difficulties are experienced by all trappers as they journey across the unstable ice that now characterizes the lake. While Schreyer believed that some construction work would be available to the people, an analysis of this work has demonstrated not only that South Indian Lake residents received the lowest paying and shortest term employment, but that this employment may have contributed to economic problems in the traditional industries of fishing and trapping by drawing people away from these industries at a crucial period in their redevelopment. [15]

With the decline in traditional economic activities, there has not been a corresponding increase in wage labour or other alternative economic activities. So the “benefits” outlined by Schreyer have proven increasingly burdensome. As one resident stated, “Hydro promised us a new town, but they didn’t say how much it was going to cost us.” [16] Indeed, the electric bills of South Indian Lake residents, especially in winter, are enormous, compounded by the fact that the new homes operate on electric heat, and are poorly insulated and difficult to keep warm. Here we have the paradox of a community asked to make a sacrifice to allow for a hydro development but unable to afford its own hydro bills! As the waters of Southern Indian Lake flow by on their way to the generating stations on the Nelson River, South Indian Lake residents experience the outrageous indignity of having their electricity cut off, even in mid-winter, as a result of their failure to pay their hydro bills. And their ability to pay these bills has been seriously undermined by the damage caused to their economy by the hydro dam.

The promise that hydro development would bring prosperity to northern Native people has simply not been realized. Definitely there have been some benefits, and these people would not now turn their backs on new homes, electricity and roads, or the trappings of “modernization” which came with the dams. But “modernization” as perceived by Manitoba Governments in the decades of the 1960s, 1970s and even 1980s is not the same thing as “development.” Providing infrastructure and services is only the first step in the development process, but in Manitoba the government seems to be stuck at this point.

This situation has not changed greatly in recent years. The communities of Easterville and South Indian Lake have recovered from the initial shocks of relocation and flooding, and have survived a period of severe social distress to enter a new period of cautious, but encouraging, development. However, the hydro legacy remains: the high water levels and floating debris in the lakes; the dispersed fish populations; the memory of residents whose fates were sealed on the unstable ice; the promises made to secure the economic future of the Native residents and the remnants of these broken promises. Like the promises of the treaty signed generations earlier, the promise of hydro development providing a new future for the northern Native people has been an empty one. And while the White southerner continues to enjoy the benefits of hydro power, the Native northerner is reminded of this bitter legacy every time he looks out his window at his lake.

1. Some of the data presented in this paper was previously published by the author in the Canadian Journal of Native Studies 4, No. 2 (1984), under the title, “Hydroelectric Development and the Process of Negotiation in Northern Manitoba, 1960-1977.”

2. For a full treatment of the relationship between treaty and hydro negotiations, see: James B. Waldram, As Long As The Rivers Run: Hydroelectric Development and Native Communities in Western Canada (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1988).

3. In this paper, I use the term “Native” to collectively describe the Indian and Métis inhabitants of northern Manitoba.

4. S. W. Schortinghuis to Chief Donald Easter, 7 June 1962. Also known as the “Letter of Intent” or the “Forebay Agreement.”

5. Lake Winnipeg, Churchill and Nelson Rivers Study Board, The Chemawawin Relocation, Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 2, App. 8, Appendix H, 1974, p. 224.

6. Minutes, Grand Rapids Forebay Committee, Chemawawin, 22 March 1962.

7. Interestingly, a Community Development Officer was eventually stationed in the community to assist the people, but only after the Forebay Agreement had been signed.

8. Schortinghuis to Easter, 7 June 1962.

9. Manitoba Hydro, “Grand Rapids - Power Development by Manitoba Hydro,” Winnipeg: Manitoba Hydro, n.d.

10. Robert Chambers, ed., The Volta Resettlement Experience, New York: Praeger, 1970.

11. The treaty Indian residents of South Indian Lake are members of the Nelson House Band, who began migrating north from that reserve in the 1920s.

12. Manitoban, Special Supplement, Nov. 1974, p. 5.

13. Edward Schreyer to Residents of South Indian Lake, 31 January 1975. Copy of letter in author’s possession.

14. Edward Schreyer to Residents of South Indian Lake, 31 January 1975. Copy of letter in author’s possession.

15. James B. Waldram, “Hydroelectric Development and Native Employment in Northern Manitoba,” Journal of Canadian Studies Fall, 1987 (in press).

16. James B. Waldram, “Hydroelectric Development and the Process of Negotiation in Northern Manitoba, 1960-1977,” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 4, No. 2 (1984), p. 231.

Page revised: 23 October 2012