by Sharon Babaian

Winnipeg

Manitoba History, Number 4, 1982

|

Q. How did the debates originally get started?

They were started in the spring of 1975 by Henry Huber and myself. Both of us were teaching at Gordon Bell High School at the time and we thought that a series of debates would be an interesting way of presenting certain topics in Canadian history to our students. We invited the history department and students of Sisler High School to join us in what became the First Annual Inter-School Canadian History Debates.

Q. Was there any particular reason why you chose the debate format to encourage your students’ interest in history?

There were several reasons for our choice. It seems to me that this format has a great deal to offer both as a general teaching method and as a means by which to develop a sound understanding of Canadian history among high school students. First of all, because we chose to involve more than one school, the debates provide students with the opportunity of meeting young people from other schools and areas of the city with whom they share similar interests. Secondly, in preparation for the debates, students not only learn the forms and rules of formal debate but they also gain important practical experience in developing logical arguments and ideas. Generally they find the debates challenging and work hard to prepare for them, discovering, in the process, some of the advantages of cooperative effort. More specifically, of course, they are investigating some significant episodes in Canadian history using, for the most part, their own methods and ideas. At the same time, both the research and the debates themselves demonstrate to the students that history is not simply a collection of dates and details or important people and events, but that it is a controversial subject full of disputes, arguments and differing opinions and one in which themes are just as important as ‘the facts.’

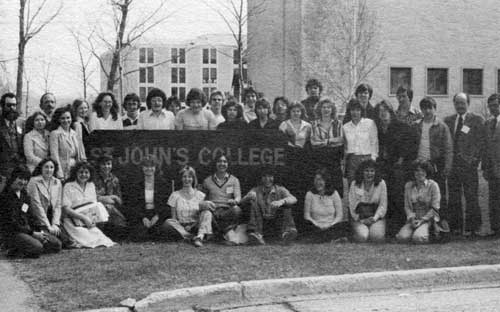

John Ingram (right), in discussion with Morris Mott and students.

Q. Could you explain how the debates are actually set up?

Each year the Canadian history teachers from the four participating schools get together and work out four topics for debate. We try to agree on topics which are controversial and which will show the value of history and its relation to current problems and events in Canada—for example, “Canada’s immigration policy from 1870-1911 would be appropriate today;” “A separate Quebec will benefit all;” “Women’s suffrage came before its time in Manitoba;” “Riel’s execution in 1885 marked the end of the new nation.” We then set the time and place for the debates and the day’s schedule which sees each team debate twice. From 1976 to 1978 the debates were held at Sisler High School. Since then we have met at the University of Manitoba (1979), Gordon Bell (1980), and Daniel Maclntyre (1981). From 1976-78 the participating schools were Sisler, and Daniel Maclntyre, Glenlawn and Gordon Bell, but since then Kelvin has replaced Glenlawn so that now all the participants are from the same school division.

Two to three weeks before the debates those grade eleven history students interested in participating in the debates are given their topics and begin their research. This stage of the work can involve any number of students, but the debate itself is limited to three speakers. The first speaker is allowed four minutes, the second is allowed three and the third and final speaker is allowed a two minute rebuttal. The debate chairmen are chosen from the participating schools but they cannot chair debates involving their own schools. Following the speakers two commentators offer their assessments of the debate and their views on the topic. These commentators are usually professors or other experts on particular issues in history and their remarks are both helpful and interesting. The debates are not competitions but forums for discussion and learning so they do not judge the teams but only add ideas and information. During the general discussion which follows their formal remarks they answer questions and discuss the topic allowing those who did not speak in the debate a chance to offer their opinions. This process is repeated for each of the four topics so that the debates last for a full day.

Q. Why do you think the debates have been so popular and successful?

I think there are three factors which year after year have contributed to their success—the interest and enthusiasm of the students, the dedication of the teachers and the competence of the commentators.

Q. Do you have any advice for teachers in other schools who might want to set up a similar series of debates?

Yes, I think I would advise them to try to stick to controversial topics which have some current significance and which relate in some way to Manitoba’s past. We have had very good luck with Winnipeg General Strike topics. Also let the students develop their own ideas and organize their research. Once you have set the topics, explained the format and perhaps have offered some general advice, the students, in my experience, have shown more than enough interest and enthusiasm to carry the debates through with a minimum of staff intervention. Always keep your students front and centre. By using participation in the debates as part of their term credits you can be sure, if you have any lingering doubts, that the students will take the whole thing quite seriously. If at all possible the inter-school format should be used because it adds a social element that is very attractive to high-school students. Debate day can be-come a very popular school event: it certainly is at Sisler.

Q. What other methods or ideas do you use to encourage your students to enjoy history.

I try to de-emphasize ‘acts and facts’ by showing students the history around them in buildings, in people, and in artifacts. Winnipeg and Manitoba have a great deal to offer in this area. Walking tours of Winnipeg’s warehouse and Old Market Square districts are quite popular and Macdonald and Ross Houses are also well worth taking in for teachers and students. There are many more examples of local history here that can be used to show young people that history is not really something distant and far-removed from our everyday lives.

Page revised: 1 January 2011